Every year the Westcott Street Cultural Fair opens Syracuse’s eyes to what a city street can really be. For a few hours, Westcott Street—normally a no-man’s land reserved for the operation of heavy machinery—is given over to the community and filled with people, and it’s great.

Streets are Syracuse’s primary public space. They take up 3,270 acres. That’s 23% of all the land in Syracuse, and it’s three times more space than all city-owned parkland. There’s plenty of room to pedestrianize a few blocks and improve the public space that’s right outside people’s front door.

Streets in neighborhood commercial districts like Westcott are particularly well-suited to pedestrianization because surrounding businesses give lots of different people a reason to be in the space. This maximizes its use and fills it with the eyes and ears that are the best way to make public spaces feel safe. That’s what makes Hanover Square so successful, and it’s why City Hall should replicate this kind of public space across Syracuse in places like Walton Street, Amos Park, and Hawley-Green.

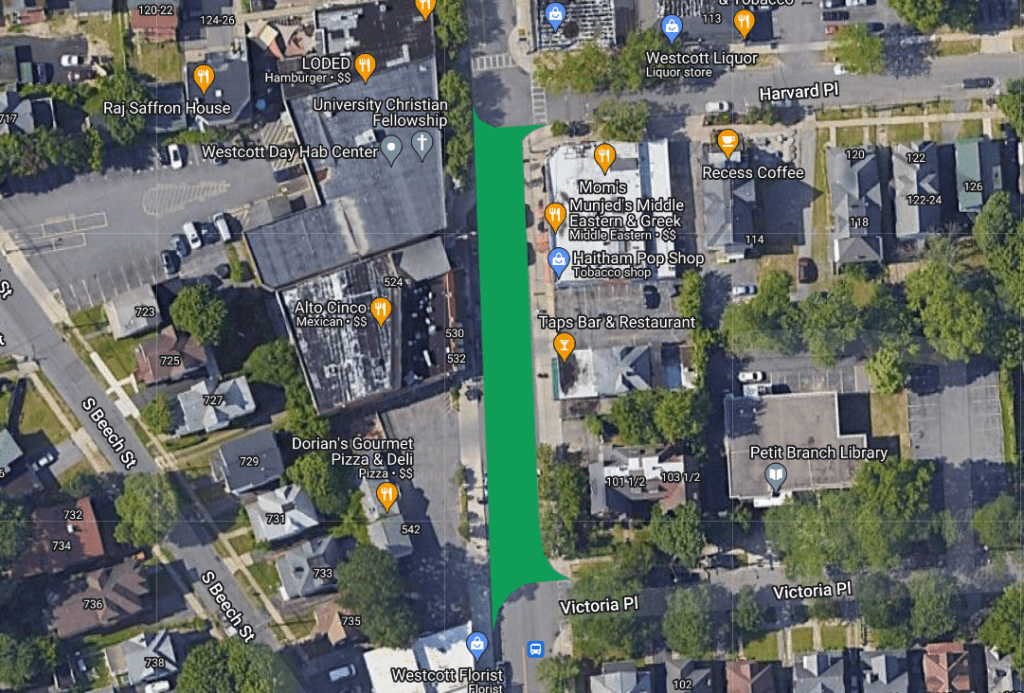

But pedestrianizing Westcott Street—between Harvard Place and Victoria Place, say—would differ from Hanover Square because it would make a much larger impact on traffic patterns in the surrounding blocks. The 100 block of East Genesee Street is—in terms of traffic circulation—redundant. Nobody needs that blocks to get from point A to point B, so closing it to cars didn’t really matter to most drivers. Hanover Square is a destination rather than a through-route.

Westcott Street is both a destination and a through-route. A lot of the traffic on Westcott is definitely bound for the business district and wouldn’t be particularly affected by pedestrianizing a single block. But Westcott is also part of a north-south route that links Teall Avenue, 690, and Colvin Street, so a lot of car drivers on Westcott Street are on their way somewhere else, and turning a portion of that route into better public space would change their behavior.

This makes pedestrianization on Westcott more complicated, but it also would make it more impactful. It would be more complicated because City Hall would need to account for changes in traffic patterns. It will be important to beef up traffic calming on surrounding streets like Columbus and Fellows Avenues so that they don’t see increases in the kind of speeding already so common on Westcott. Two Centro routes currently use this part of Westcott, and they would need to be accommodated as well. Those are solvable problems, but they present technical—not to mention political—challenges that would make pedestrianizing Westcott a harder lift than Hanover Square was.

But solving those challenges would have enormous benefits that go beyond what Syracuse has already seen in Hanover Square. Turning 1 single block of Westcott Street into public space would significantly reduce car traffic—and particularly high-speed through-traffic—on many surrounding blocks. This would make the neighborhood significantly safer, healthier, and livelier. Existing surface parking lots fronting the new pedestrian square would become much more valuable for new retail space and much needed housing, and the resulting increase in foot traffic would support more of the kinds of local businesses that make Westcott such a popular neighborhood.

This virtuous circle—walkability reduces car dependence, which allows increased residential density, which creates demand for neighborhood scale retail, which improves walkability, which reduces car dependence, which…—is the core of what makes urban neighborhoods successful and resilient, and City Hall should be doing all it can to jumpstart that cycle in neighborhoods across Syracuse.

Syracuse absolutely needs more quality public space, and the easiest way to build it is repurposing portions of our most common public property—city streets—into city squares. Existing projects like Hanover Square have tried to accomplish this without changing car traffic patterns too much, but Westcott Street shows how a bolder strategy could have a bigger impact and make our neighborhoods safer, healthier, and livelier.