This is a proposal for an intercity transit service connecting the region of Upstate New York that includes the cities of Syracuse, Cortland, and Ithaca. The region currently contains much of the infrastructure and conditions necessary for successful intercity transit, but what service actually exists is infrequent and disjointed. This proposal consolidates and extends existing service to make it more useful and efficient for the region as a whole.

Route

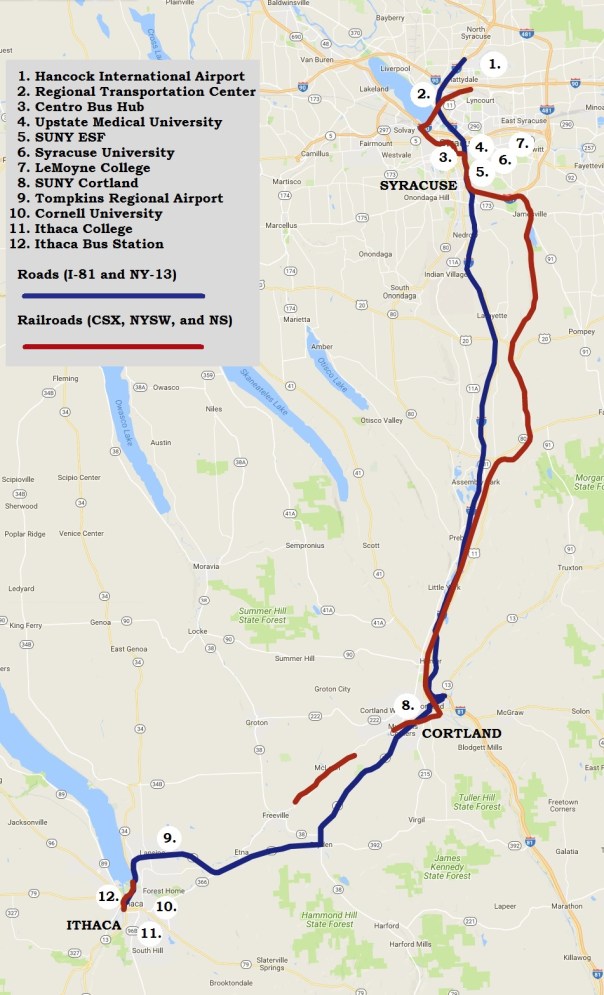

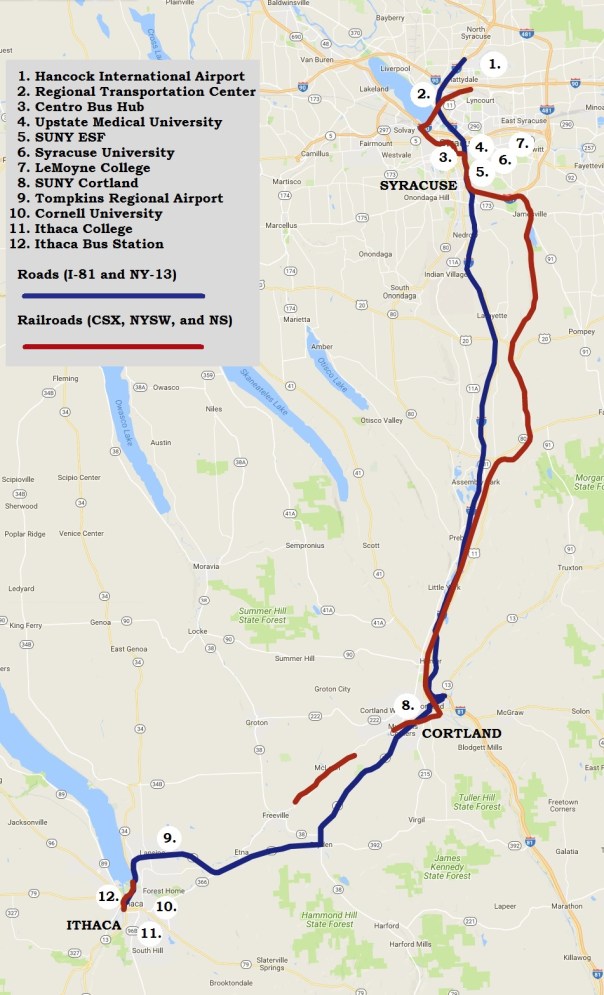

The proposed transit service would run through a corridor approximately five miles wide and seventy miles long. That corridor stretches from the Hancock International Airport (SYR) through Cortland down to Ithaca. From Syracuse to Cortland, the service would run through the relatively flat and straight valleys carved by Onondaga Creek, Butternut Creek, and the Tioughnioga River, climbing 750 feet over the course of roughly 40 miles. From Cortland to Ithaca, the service would follow a much more irregular valley carved by several small streams before descending 400 feet in less than a mile to reach the City of Ithaca on the southern shore of Cayuga Lake.

There is already a good deal of transportation infrastructure along this corridor. I-81 stretches from SYR to Cortland, and from there vehicles can take NY-13 from Cortland all the way to Ithaca. Vehicles can also turn from NY-13 to NY-366 to pass through Cornell University on the way into Ithaca.

CSX owns a rail line that passes within two miles of the SYR’s passenger terminal. That line continues west through the William F. Walsh Regional Transportation Center (the RTC, Syracuse’s Amtrak and intercity bus station) to the southern end of Onondaga Lake where it connects to the New York, Susquehanna, & Western line. That railroad curves south through Syracuse, passing Centro’s Bus Hub and Syracuse University, and it continues all the way south through Cortland to the hamlet of Munson’s Corners. There is an abandoned railroad right-of-way between Cortland and Ithaca including roughly four miles of unused track near the hamlet of McLean. In Ithaca, Norfolk Southern owns track that runs from the Ithaca Bus Station (an intercity station) north along the eastern shore of Cayuga Lake and connecting to the abandoned right of way that leads to Cortland.

There are a number of regionally significant communities and institutions along the corridor. The cities of Syracuse, Cortland, and Ithaca are each the seat of their respective counties, and each serves as the center of a local transit system. Combined, these three cities and their immediate suburbs are home to more than 500,000 people. More broadly, the Syracuse-Auburn and Ithaca-Cortland combined statistical areas have a combined population of more than 870,000. There are also seven colleges and universities along the corridor with a combined enrollment of more than 63,000 students as well as two community colleges with a combined enrollment of more than 18,000 students.

Demand

The transit service will enable riders to accomplish two distinct tasks: travelling to or from a transit hub that connects to another intercity transportation service such as Amtrak or Megabus, and travelling between cities within the corridor. There is demonstrated demand for transit service that accomplishes each task.

Transportation to a Hub:

The only intercity passenger train station in the corridor is the RTC in Syracuse. The RTC is also the only bus station in the corridor served by Megabus, and the Centro Bus Hub in Syracuse provides the only intercity bus service to the cities of Oswego and Auburn.

Both the Tompkins Regional Airport in Ithaca (ITH) and SYR provide intercity passenger service. Of these two airports, SYR provides more frequent service to a larger number of cities than does ITH. Flights into and out of SYR are also generally cheaper than those at ITH. People travelling to or from the region by plane often must use SYR even if it would be more convenient to get to ITH.

The service will connect these hubs to three schools with student bodies that need to travel outside of the region frequently. Syracuse University, Cornell University, and Ithaca College enroll a combined total of 50,197 students, 68% of whom are from states other than New York and 18% of whom are from outside of the United States.

Each of those three schools struggles to transport students and visitors to and from the region’s intercity transportation hubs. Syracuse University and Cornell University run their own shuttles to and from SYR at the beginning and end of each semester and holiday break. Syracuse’s service is free, but tickets for Cornell’s service cost $30. Otherwise, Syracuse University simply suggests taking a cab to travel between SYR and the university, or taking Centro between the RTC and the university. Ithaca College offers no transportation to SYR. Both Ithaca College and Cornell suggest that those who need to get either to or from SYR or the RTC can book a ride with the Ithaca Airline Limousine, a private transportation service that can make up to eight runs between Syracuse and Ithaca every weekday and costs $85 for a one-way ticket or $130 for a two-way ticket.

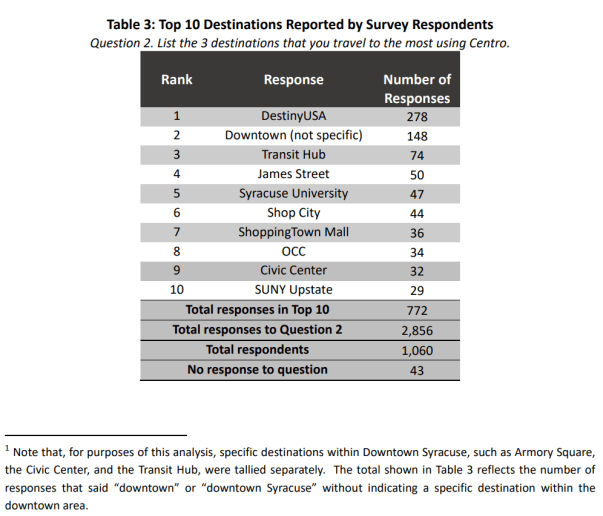

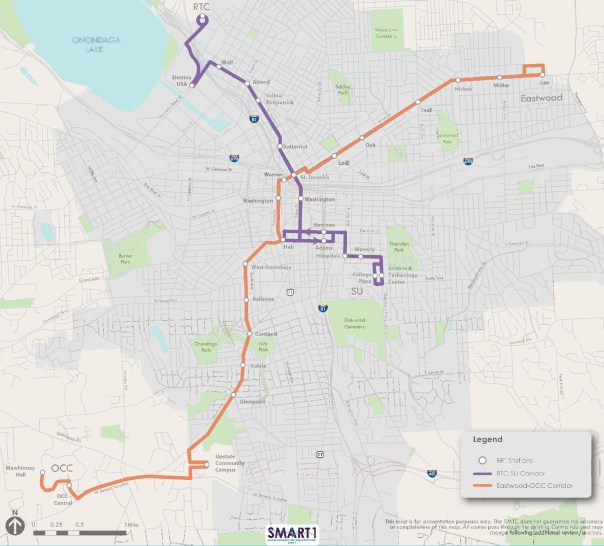

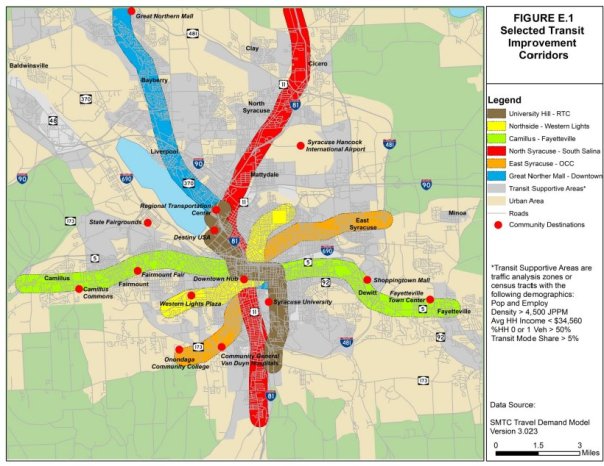

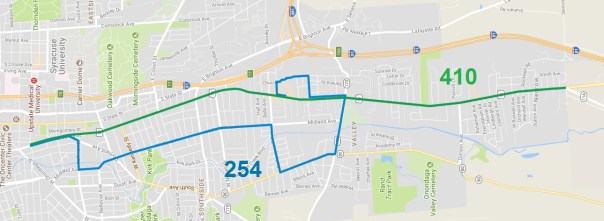

The Syracuse Transit System Analysis (STSA) also identified the need for improved transit service to both the RTC and SYR. The STSA selected the route from Syracuse University to the RTC as a ‘transit improvement corridor’ because of the presence of jobs, carless households, and demonstrated demand for transit along the route. The STSA also recommended the creation of a shuttle service running every half hour between SYR and the RTC to serve airport passengers and employees.

Additionally, other travelers arriving in the region by bus, train, or plane will benefit from improved transit from the intercity transit hubs to destinations such as convention centers and hotels in each city.

Transportation Between Cities:

Centro and Cortland Transit already provide limited intercity transit for commuters. Commuters from Cortland County can catch an express bus to Syracuse from Centro’s Park-N-Ride facility in the Village of Tully. Centro also provides commuter service from both Oswego and Auburn to Syracuse. Cortland Transit runs a commuter service between Cortland and Ithaca.

26% of all workers in Ithaca, Cortland, and Syracuse commute by some mode other than a personal vehicle (public transit, bike, taxi, or on foot). Improved intercity transit between these cities would improve economic opportunity for these workers and encourage intercity commuting. There are 1.3 jobs per household in both Cortland and Ithaca, but only 1.0 jobs per household in Syracuse. Despite the high proportion of jobs to households, median household income is lower in Ithaca ($30,436) than in Syracuse ($31,881) or Cortland ($40,025). At the same time, housing costs are much higher in Ithaca (median property value: $220,000) than in either Syracuse (median property value: $88,800) or Cortland (median property value: $94,200). Workers currently living in Ithaca could more easily move to Syracuse or Cortland for the low housing costs, while people in Syracuse could apply for the relatively more plentiful jobs in Cortland or Ithaca.

Improving transit between Ithaca, Cortland, and Syracuse will increase opportunities for collaboration between the seven colleges and universities in those cities. Currently, each school in Syracuse allows some students to take classes for credit at at least one other school in the city, and Cornell University maintains an exchange program with Ithaca College. Faculty from the seven schools also frequently collaborate on research. Similar programs and cooperation will be possible between schools in different cities when they are connected by reliable frequent transit.

Adjunct professors provide one example of how improved economic opportunity is connected to increased collaboration between the region’s colleges and universities. 26% of the 5,727 faculty employed by the six schools are non-tenure track part time instructors. These adjunct faculty are paid several thousand dollars a semester for each course that they teach. The people who work these jobs often need to teach classes at multiple schools in order to make ends meet. The proposed transit service would broaden the opportunities available adjunct faculty in Ithaca, Cortland, and Syracuse by allowing them to teach more easily at multiple schools in different cities. This would make the region more attractive to recent graduates of all those schools, and it would help the region retain a highly educated workforce.

Additionally, there are unique resources in each city–such as Syracuse’s hospitals and specialized medical centers–that will attract riders from elsewhere along the proposed transit line.

Existing Service

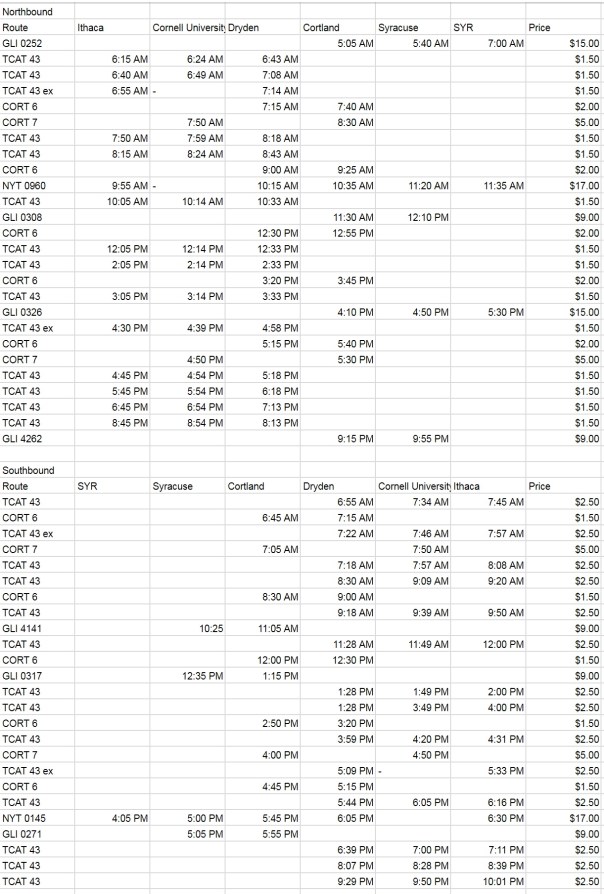

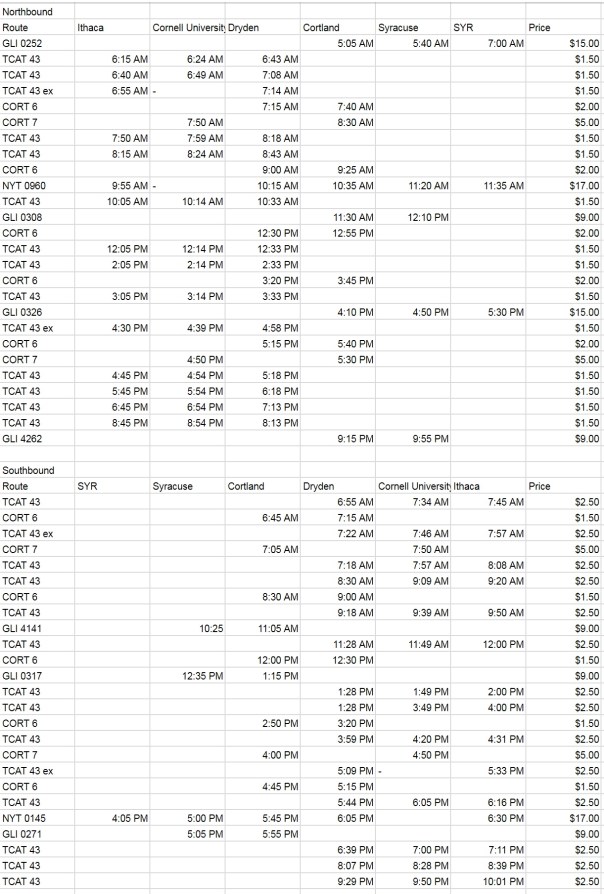

Currently, two intercity bus lines (Greyhound and New York Trailways) and three local transit authorities (Centro, Cortland Transit, and TCAT) provide service along the corridor. Many of these services overlap, making it possible to travel a great distance within the corridor by making transfers at important junctions. Here is a table of all connecting weekday service currently available within the corridor.

Although these different bus services can take a rider pretty far, it is very difficult to travel the corridor’s entire length. New York Trailways offers service once a day in each direction between Ithaca and SYR, and it is possible to use regional transit to travel from Ithaca to SYR at only one other time on any weekday. Here is a table of all connecting weekday service from Ithaca to SYR currently available within the corridor.

Using currently available service, a rider trying to get between SYR and Ithaca will have to pay either $16.50 or $17.00 to take a ride lasts between 100 and 205 minutes.

Proposed Transit Service

Stops:

The proposed transit service should run from SYR to the Ithaca Bus Station and make intermediate stops at the RTC, the Centro Bus Hub, Syracuse University, the Cortland County Office Building (Cortland Transit’s main transfer point), and Cornell University.

Stops at the Centro Bus Hub, Cortland County Office Building, and Ithaca Bus Station will enable residents of all three cities to transfer between Centro, Cortland Transit, TCAT and the proposed transit service. By making these stops, the proposed service will be able to transport people to and from their homes.

Stops at SYR, the RTC, and the Ithaca Bus Station will enable people travelling to or from the region by train, plane, or bus to to transfer between those transportation modes and the proposed transit service. By making these stops, the proposed service will connect the region to a national transportation system.

Stops at the Centro Bus Hub, Syracuse University, Cortland County Office Building, and Cornell University will enable people to reach the centers of employment in all three cities. By making these stops, the proposed service will be able to transport people to and from their jobs.

The service could also make additional stops at the Village of Tully, Tompkins Cortland Community College, and/or ITH in order to allow local transit authorities to eliminate some existing service and redirect funds to support the proposed service.

Mode:

The proposed transit service should operate as either a bus line or rail line. Much of the infrastructure necessary for either mode is already in place, and each option has its own advantages and disadvantages.

As a rail line, the proposed transit service would follow a roughly 70 mile long route from SYR to the Ithaca Bus Station with intermediate stops at the RTC, the Centro bus hub, Syracuse University, and Cortland. The line would follow 48 miles of existing rights-of-way from the RTC to Cortland and in Ithaca, and it would require 22 miles of new rights-of-way between the RTC and SYR, and between Cortland and Ithaca.

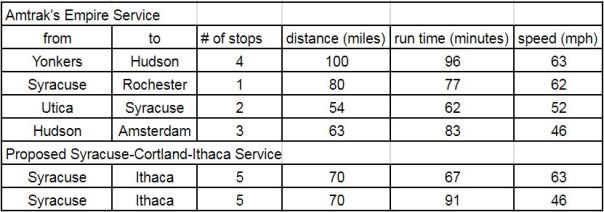

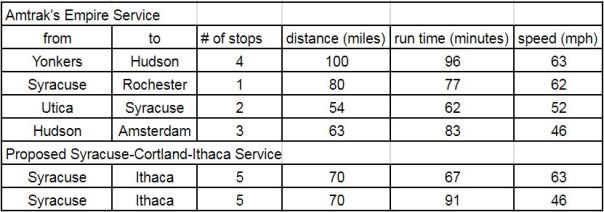

A rail line could run at high speeds unimpeded by traffic. Amtrak trains run at speeds between 46 and 67 mph on similar stretches of track elsewhere in Upstate New York. At those speeds, a train would complete the entire run between SYR and the Ithaca bus station in 67 to 91 minutes. That’s significantly faster the 120 to 150 minutes that a bus would take to make the same run.

As a bus line, the proposed transit service would follow an approximately 68 mile route from SYR to the Ithaca Bus Station with stops at the RTC, Centro Bus Hub, Syracuse University, Cortland County Office Building, and Cornell University. The line would follow I-81 from SYR to exit 11 at Cortland, making stops at the RTC, the Centro Bus Hub, and Syracuse University on the way. From exit 11, the line would follow NY-13 through Cortland and Dryden before taking NY-366 to Tower Road and Cornell University. From Tower Road, the line would continue through Ithaca to the Ithaca Bus Station.

Operating the proposed transit service as a bus line eliminates the need to purchase, build, or negotiate for any inch of right-of-way. This would make the proposed transit service much less expensive upfront. Using existing roadways also would allow the transit service to stop at Cornell University, a stop that is inaccessible to rail because of the steep grade that separates the university from the Ithaca Bus Station. Finally, because existing roadways can accommodate two-way traffic, multiple buses could run along the line simultaneously, allowing for more frequent service. This would be impossible for a rail line because almost all of the existing rail infrastructure is single-tracked, meaning trains running in opposite directions cannot pass each other.

Schedule:

A rail service could make the round-trip in 180 minutes. Running continuously from 6:00 am to 9:00 pm, a train could make five round-trips between SYR and the Ithaca Bus Station. At higher speeds, a train could make the round-trip in less time, allowing for more runs in the same amount of time.

A bus service could make the round-trip in 270 minutes. Running continuously from 6:00 am to 7:30 pm, 2 buses could make six trips from SYR to the Ithaca Bus Station and six trips from the Ithaca Bus Station to SYR. More buses could make more runs in the same amount of time.

Operating on these or similar schedules, the proposed transit service would facilitate intercity commuting, and it would facilitate transfers to other intercity buses, trains, and planes.

Fare Structure:

The proposed transit service should charge zone-based fares with significant discounts for multi-ride or monthly passes. This fare structure will allow the proposed transit service to compete for both regular commuters and for riders travelling between cities infrequently. Here are two potential ways to divide the proposed transit line into zones with one-way fares that can compete with all currently available transportation options.

Conclusion

A transit service between Ithaca, Cortland, and Syracuse would benefit the entire region by connecting centers of population, employment, local transit, and intercity transportation. Such a service would build on the region’s strengths by facilitating travel to and between its many academic and research institutions, making them more attractive to students and scholars from outside the region, and more accessible to workers from within the region.

The main obstacle to establishing this service is cooperation. The service would run through, and require the support of, three different counties, three different cities, three different transportation authorities, many more towns and villages, and several large private institutions like Cornell University and Syracuse University. Very few of these entities have regular cause to work together, but this transit service has the potential to get them to cooperate on a single project, to start thinking of each other as part of a unified region with common goals and interests. That would be a big change in Upstate New York, and it would be the best thing this transit service could do.

For more reading on this proposal, click the links below:

Learning from OnTrack

University Students and Public Transportation

Uniting Communities through Transit