City Hall wants to legalize Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs, or small 1-bedroom apartments built in extra space on a residential property). That’s good, but in order to secure all the benefits that this type of housing can offer, City Hall will have to do more than just list it as an ‘allowed use’ in the zoning code—ReZone will also have to adjust other regulations that would functionally ban ADUs in most of the City if enacted as drafted.

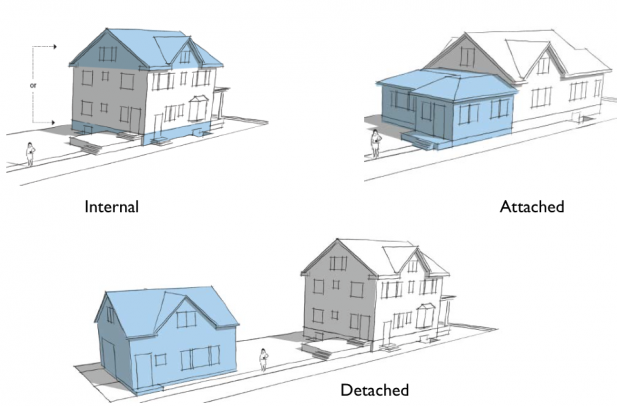

ADUs (also sometimes called in-law apartments or granny flats) are a traditional housing type that used to be common in Syracuse and cities across America. Families that needed a little extra money to afford a mortgage—adults who wanted their aging parents close by to help with childcare—parents whose adult children who’d moved away and left the house mostly empty. People in all of these situations responded by turning some small part of their property—maybe the attic, or by building a garage with living space above—into an additional apartment where another person could live in privacy.

ADUs were banned from many cities during the era when planners and politicians tried to apply suburban ideals to urban neighborhoods. They thought it was strange and slightly deviant for unrelated people to live near each other, so zoning codes—like Syracuse’s—reserved a lot of residential land for single-family homes only and banned other traditional housing types including ADUs.

But ADUs are becoming popular again for the same reasons that they were popular in the past. People want the flexibility to adapt their property to meet their family’s needs. We’re not all picture-perfect midcentury sitcom families with identical needs that can all be served by suburban-style houses. ADUs are a good way to make Syracuse’s housing stock work for more people.

So it’s a very good thing that City Hall is amending ReZone to allow ADUs in all residential districts. Previous drafts of the new zoning law had excluded ADUs from any lot zoned R1, but in a February presentation to the Common Council, City Planner’s implied that the new draft would allow ADUs in R1 as well as all other residential districts.

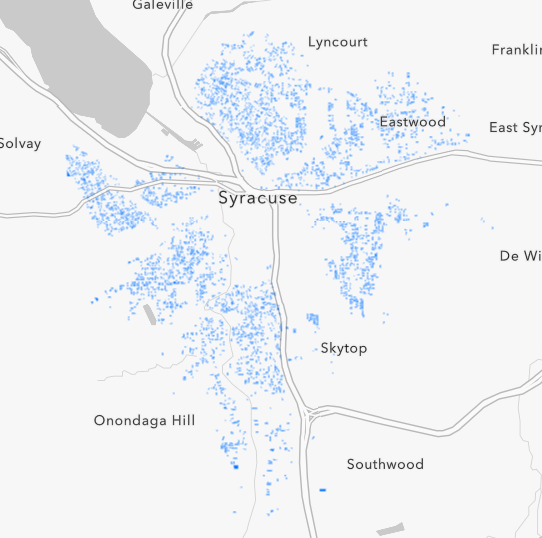

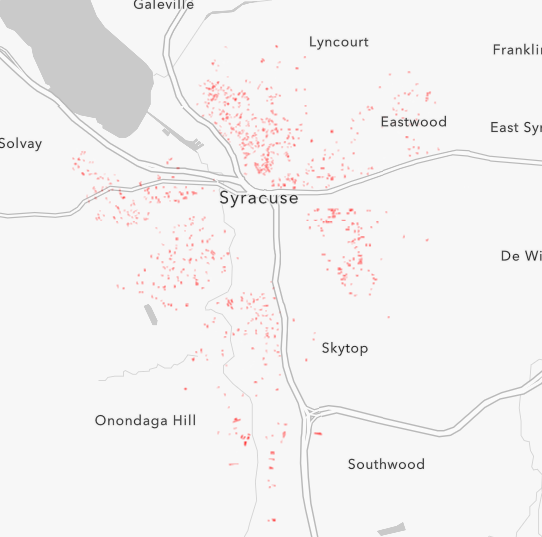

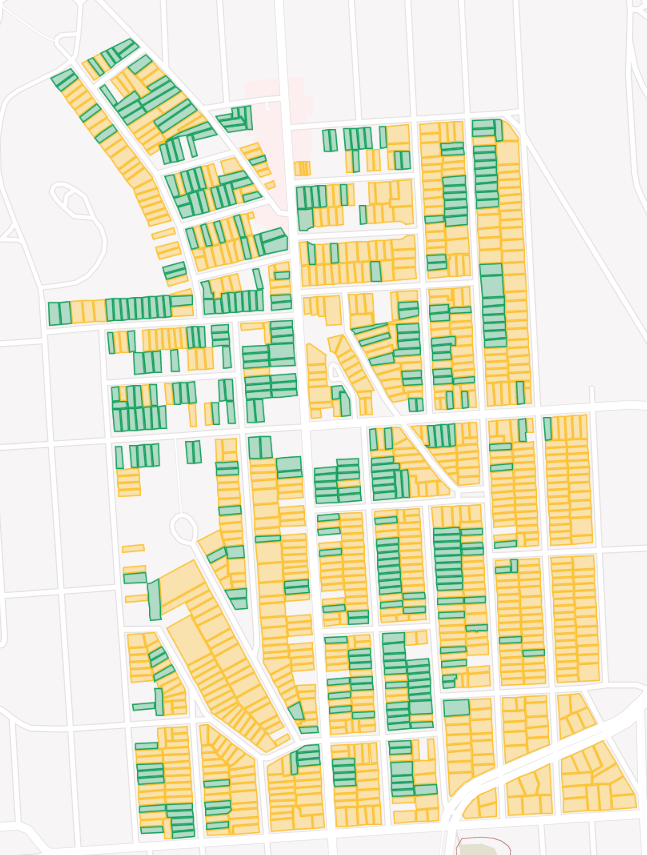

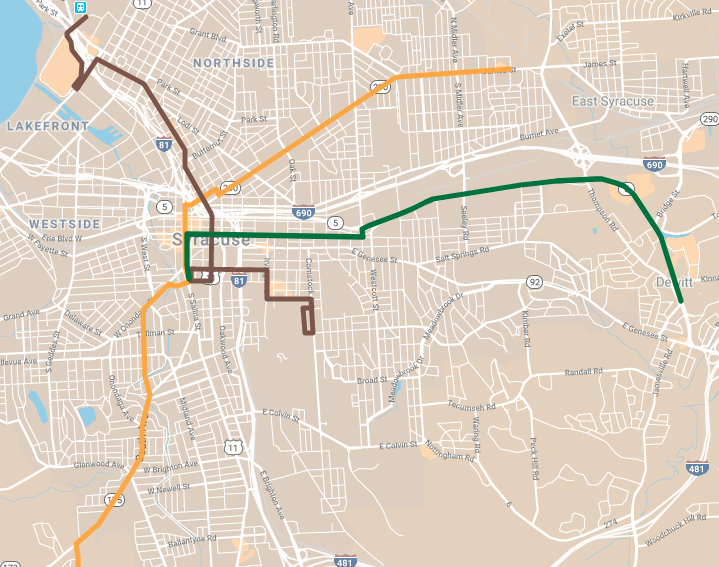

However, the current draft outright bad on ADUs is not the only regulation that would make them a practical impossibility for most homeowners—lot coverage regulations are another barrier. ReZone says that built structures can only cover 30% of the area of residential lots with single-family homes. But most homes in most Syracuse’s neighborhoods (except its post-war semi-suburban areas like Meadowbrook and Winkworth) already cover more than ⅓ of their lots. In these situations, it would be impossible to build an ADU in the rear yard (either as a standalone structure or as an addition to the house) even though the rest of the ordinance is written to encourage that kind of construction.

This coverage requirement isn’t about environmental considerations like stormwater runoff. Homeowners are allowed to cover much more of their lots—up to 65%—with impermeable surface so long as that extra 35% is surface parking. There’s no good reason to value space for parked cars over housing for people who need it.

So when City Hall finally releases the new ReZone draft (they promised it by March, but that deadline’s long past), look to see whether they’ve taken the necessary steps to make ADUs not just legal, but also practical for the people who need them in neighborhoods across the City.