When the Syracuse Police Department moves its main offices out of the Public Safety Building on State Street, City Hall should build a path through the property to reconnect Downtown with the neighborhoods immediately to its east.

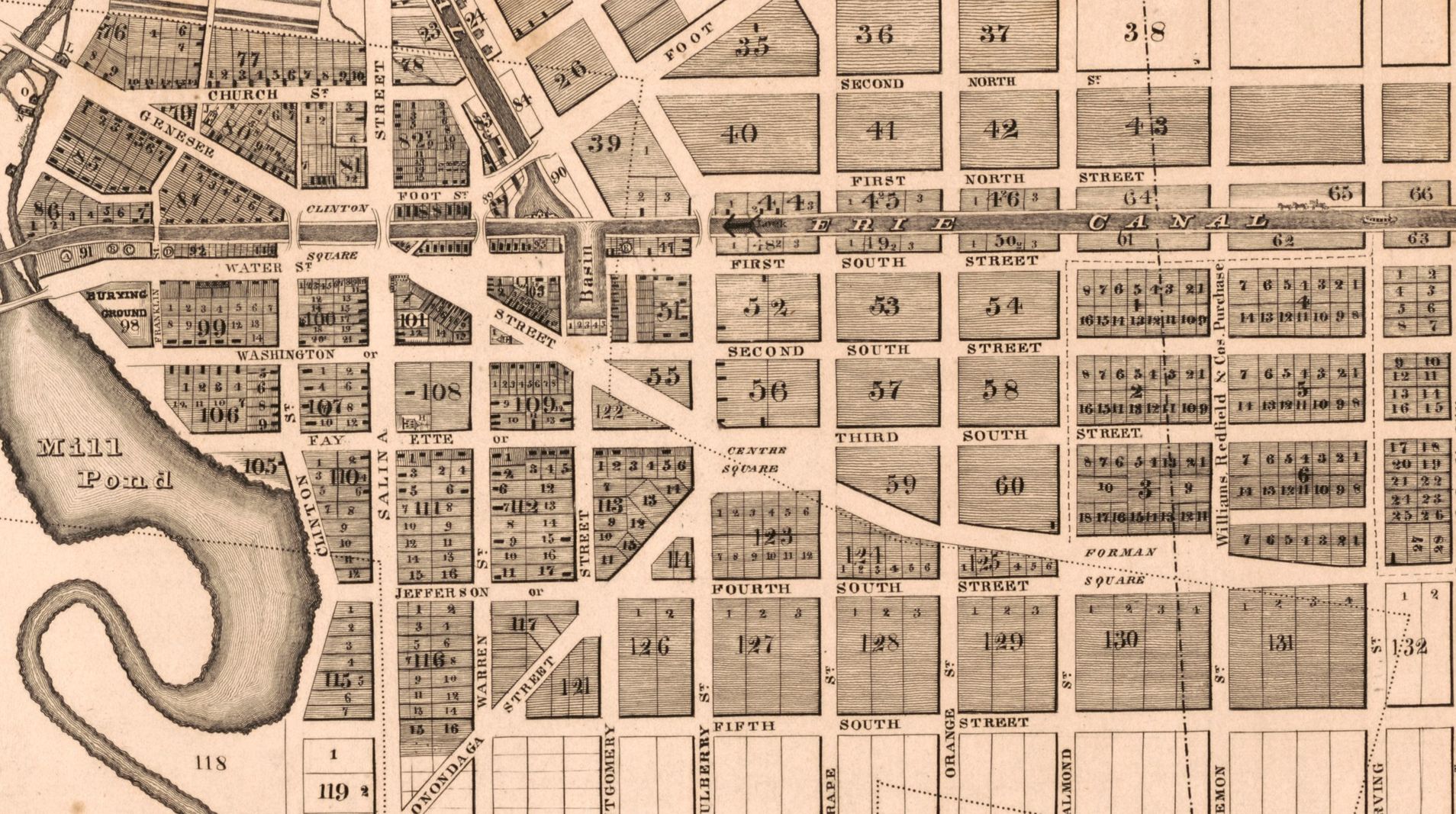

City Hall built the present Public Safety Building as part of an urban renewal project explicitly designed to cut Downtown off from Syracuse’s close-in residential neighborhoods. It did this most effectively by totally demolishing one such neighborhood—the 15th Ward—and by closing short local streets better suited to pedestrian traffic than long-distance car commuting. South of Genesee Street, five local streets used to enter Downtown from the east. Today, only two—Harrison and Adams—are left, and both are too wide and carry too many cars driving too fast to be a safe and pleasant route for anybody travelling by bike, foot, or mobility device.

If I-81’s removal is going to really change the way people get around town—and it must—then City Hall needs to find ways to reestablish those lost connections. Piercing the superblocks around the Public Safety Building is a good place to start. All three of the lost east-west connections—Jefferson, Cedar, and Madison Streets—were removed to build Presidential Plaza and the Courthouse/Public Safety Building/Justice Center/Everson Museum complex.

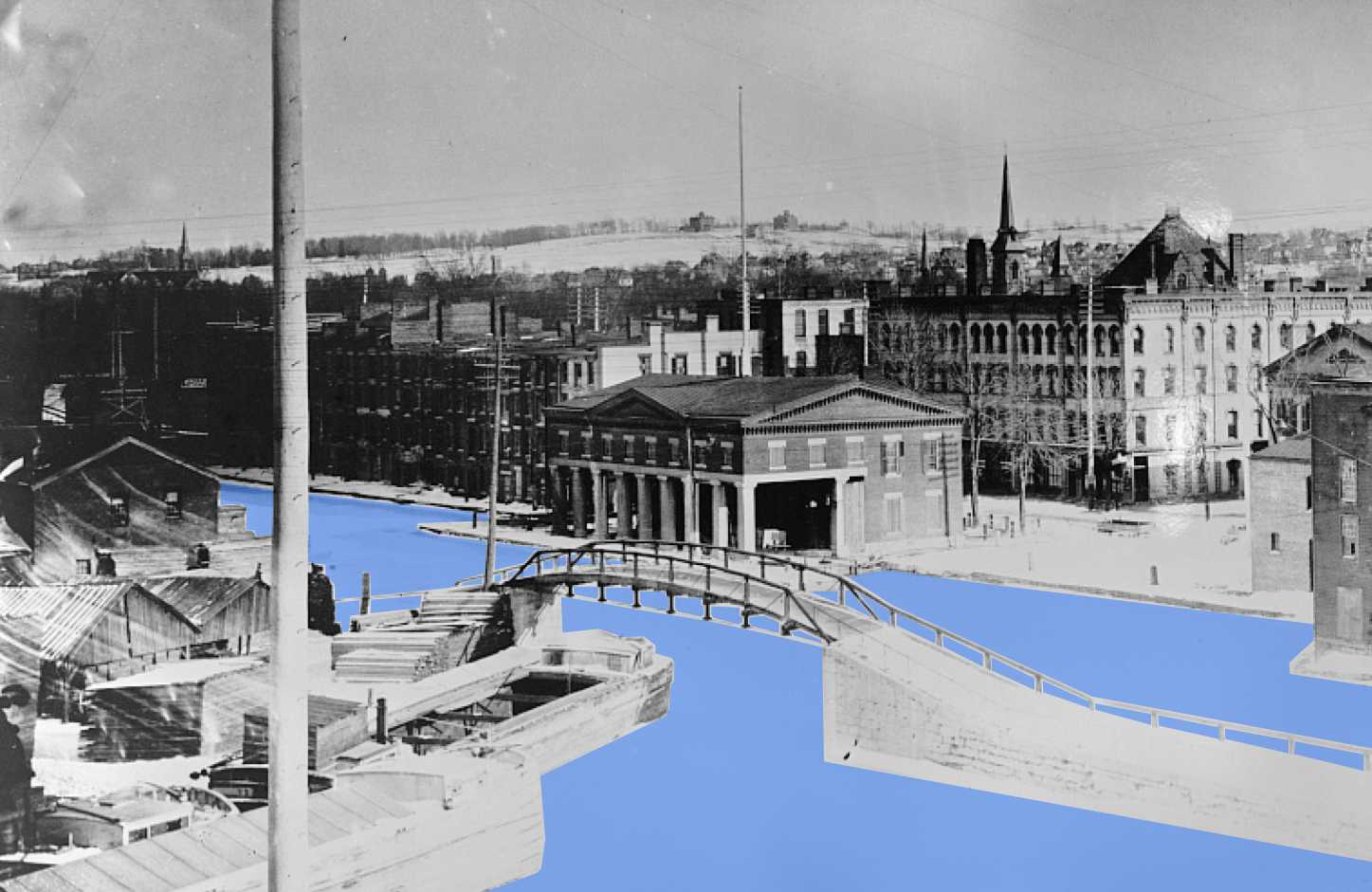

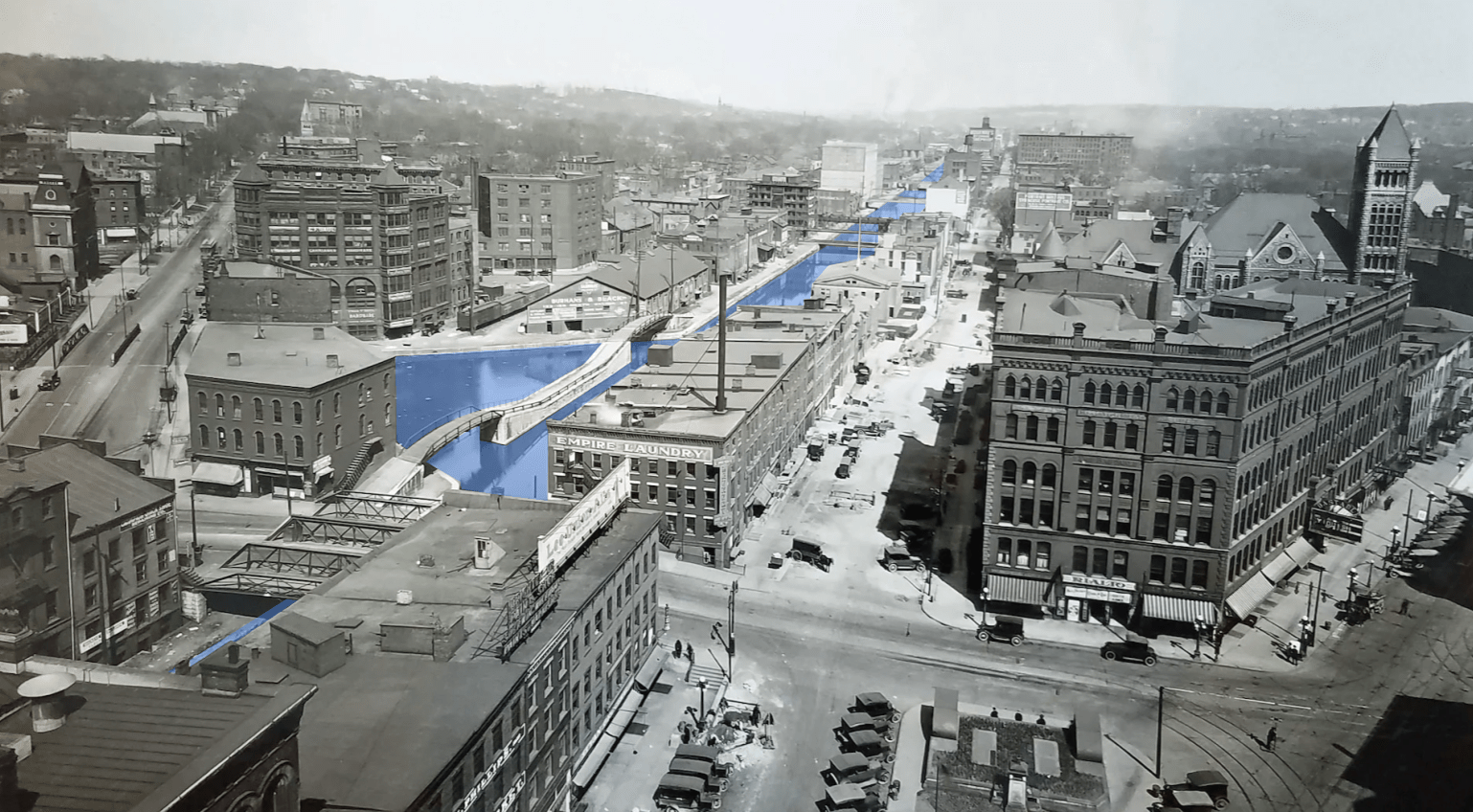

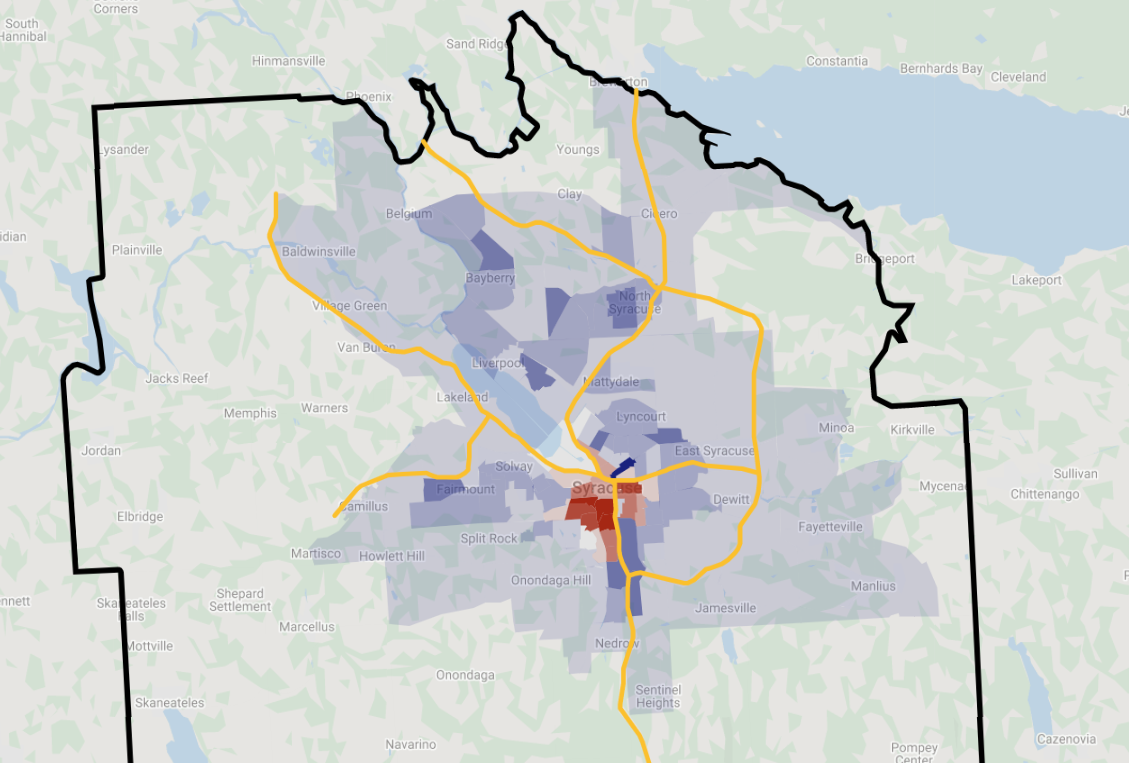

street grid removal for urban renewal superblocks

Traces of each remain. The tree-covered walk along the north side of the Everson fountain follows Madison Street’s path. Privately-owned Presidential Court sits where Cedar Street used to run. Eastbound traffic on Genesee Street runs south of Forman Park on what used to be the easternmost block of Jefferson Street.

But although there are pieces of all these old streets, they are disconnected and do not form a path between University Hill and Downtown. Urban renewal superblocks, highway offramps, and a distinct lack of crosswalks all conspire to create a sort of pedestrian black hole between State, Genesee, Harrison, and Almond Streets.

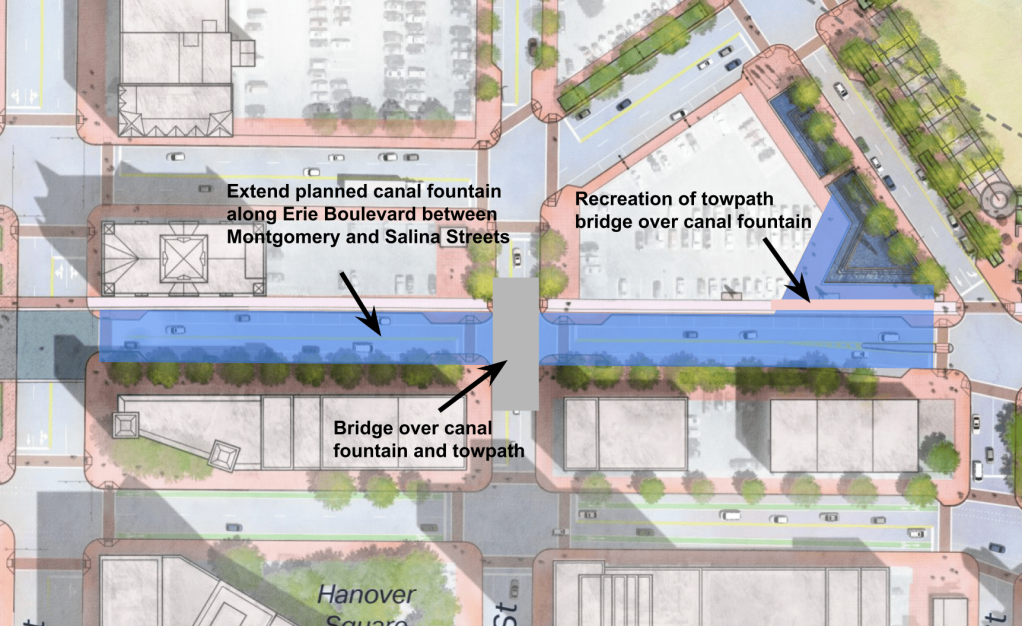

traces of Cedar Street between Montgomery and Almond Streets

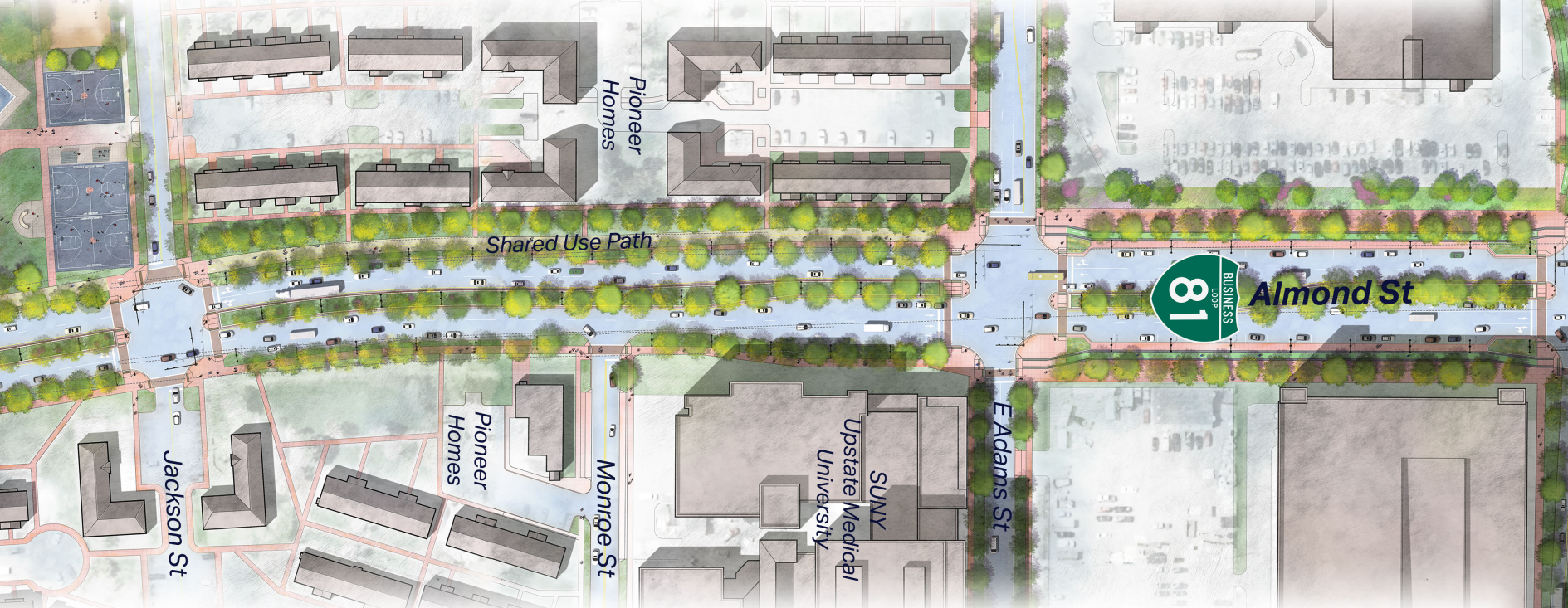

I-81’s demolition and the police department’s move out of the Public Safety Building present the opportunity to restore connections to Downtown. First, City Hall should pierce the State Street superblock by building a path across it in the area of the present Public Safety Building (the remainder of the large site can be redeveloped with homes and commercial space, some of which should front the path). Second, City Hall should work with NYSDOT and Sutton Real Estate Company—the owner of Presidential Court—to reopen connections across the Presidential Plaza superblock by linking Presidential Court with Almond Street. Third, City Hall and NYSDOT should install crosswalks and traffic lights on Almond, Townsend, and State Streets where those streets intersect reestablished east-west connections.

These are the kinds of interventions Syracuse needs to reconnect neighborhoods divided by urban renewal. The City has been carved up by highways and superblocks, and people getting around on foot, by bike, or with a mobility device have too few direct, safe options for travelling between neighborhoods. A new route through the Public Safety Building property would help reconnect small safe streets like Madison, Jefferson, and Cedar and play an important part in a larger network of safe routes across the whole City.