In April 2017, City Hall published a draft of the new zoning ordinance that allowed for buildings near to “any type of bus stop, regardless of service level” to build 30% fewer parking spaces than buildings without easy access to transit. That’s was a good idea because it costs money to provide off-street parking, and that’s an unnecessary expense when the people using a building don’t travel by car. When City Hall imposes that expense on a property owner by requiring that a building have more parking than is necessary, that amounts to a tax on pedestrians, cyclists, and bus riders.

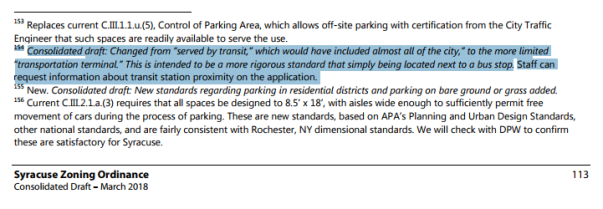

In March of 2018, the City Hall backed away from that good idea. Instead of reducing parking minimums for buildings within a quarter mile of “stations served by transit,” the new draft ordinance published that month talks about buildings within a quarter mile of “transportation terminals.” It’s not obvious what a transportation terminal would be in Syracuse (the Centro Hub, the RTC, the terminal stop for each bus line?), but it’s clear from the explanatory footnote that a transportation terminal is not a bus stop:

It’s as if City Hall didn’t know that Centro is a viable transportation option in just about every neighborhood in the City, and now they’re trying to limit the benefits that bus service can provide.

In fact, Centro’s pervasive service is a good reason to take the opposite tack and allow greater density at the corner properties on each intersection where a bus stops. Elevating the properties at each bus stop by one zoning district (from R-2 to R-3, say, or from MX-1 to MX-2) would increase the City’s capacity to house people who do not own cars, and that’s right in line with the City’s Land Use & Development Plan:

“This capacity should be preserved by maintaining zoning for density levels in line with the existing built environment, so that over the long-term the City may market its ability to cost-effectively absorb regional population growth—based on existing infrastructure and an urban land-use pattern that lends itself to walkable neighborhoods, local commercial and business services, and efficient transit service.” Land Use & Development Plan, pg 12

Luckily, the City Hall is hosting three information sessions about the new zoning ordinance this week. The first will be on Monday at 6:30 at Nottingham High School, the second will be on Tuesday at 6:30 at Corcoran High School, and the third will be on Wednesday at 6:30 at Henninger High School. Check these info sessions out, learn more about the new ordinance, and ask why City Hall wants make it harder for people without cars to find an affordable apartment in the City.