I used to rent a one-bedroom apartment on the back end of a building on the City’s Northside. The building had been a standard Syracuse double-decker—two identical three-bedroom apartments stacked one on top of the other—but at some point the owner split the second floor into two one-bedroom apartments. That was good for me because it meant there was a one-bedroom apartment that I could afford, and it was good for the landlord because the combined rent from those two second floor one-bedroom apartments was $980 a month—significantly more than the $750 a month that the three-bedroom apartment on the first floor brought in.

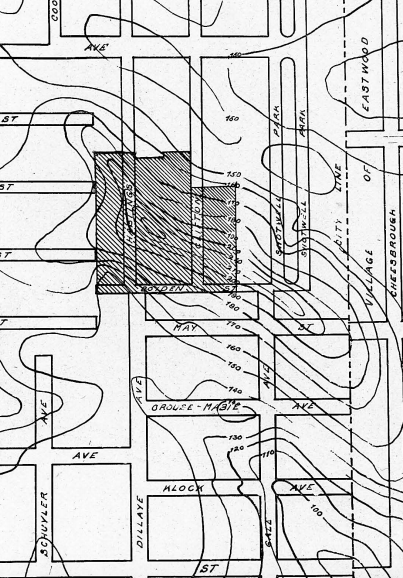

Small modifications like this one—putting up a wall and building a new kitchen and bathroom to convert a two-family building into a three-family building—make Syracuse resilient. The City is full of old buildings that have been modified over the years to better meet the needs of a changing population, and you’re most likely to find them in the neighborhoods that are most diverse and that provide people with the greatest variety of opportunity.

It’s a problem, then, that City Hall’s new zoning ordinance would make that kind of responsive modification largely illegal in so many of the neighborhoods where it’s most useful.

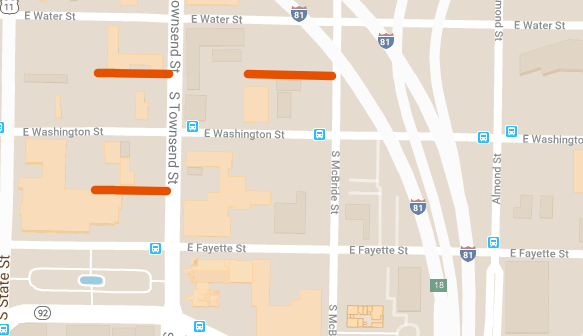

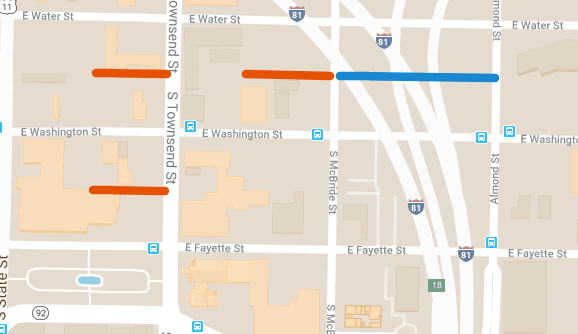

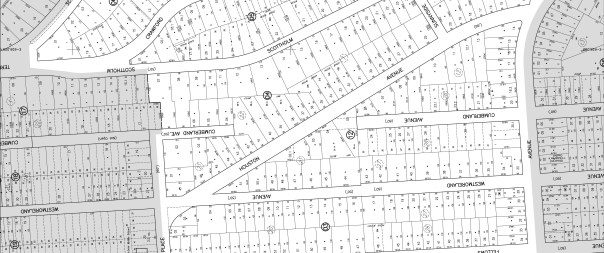

ReZone divides all residential buildings into 1 of 3 categories: one-family, two-family, or multi-family. That double-decker apartment I lived in would have originally been considered a two-family home, but now with its three apartments, City Hall will call it a multi-family home. ReZone allows two-family homes in all of Syracuse’s inner neighborhoods, but it bans multi-family housing from almost all of Tipperary Hill, the Southside, Westcott, Skunk City, and the Northside. That ban restricts people’s ability to modify their properties in the small ways that will make those neighborhoods able to cope with change.

City Hall needs to amend its draft zoning ordinance to accommodate a greater variety of housing types. The could mean adding more categories to its list of residential uses (three-family, four-family, five-family, etc.), it could mean expanding the two-family category to include other small-scale apartment buildings with more than two units (up to six, say), or it could mean getting rid of the two-family category entirely to allow all kinds of multi-family housing in every neighborhoods except those quasi-suburban spots like Meadowbrook and the Valley.

Syracuse’s strength is its flexibility. The City’s been around for about 200 years now, and the people who call it home have adapted to huge economic, demographic, and technological changes in that time. Left to their own devices, city residents will keep on doing the little things—like converting a two-family home into a 3-family home—that will keep the City responsive to the needs of the day, but those kinds of modifications will only be possible if City Hall relaxes its planned restrictions on multi-family housing. Do that, and Syracuse might just make it another 200 years.