City Hall’s “crackdown” on dirt bikes and ATVs demonstrates how an overreliance on policing can crowd out more effective methods of achieving public safety. The crackdown—an annual Spring event—includes more officers patrolling city neighborhoods trying to ticket or tow dirt bikes and ATVs.

Why this specific class of vehicles? As Mayor Walsh put it, “The return of warmer weather is bringing back behaviors that make our streets unsafe and create disturbances to quality of life… dirt bikes and ATVs are dangerous.”

Clearly, Syracuse does have a problem with traffic violence, and it does make us all less safe. Ask anybody who gets around on foot or on a bike or in a wheelchair and they’ll tell you—it’s dangerous just moving around town. Every day brings close calls, and the only reason more people aren’t injured and killed is that so many have been scared from even trying to navigate the streets in the first place.

Look at this problem through the lens of policing, and the solution is to stop rule breakers from doing illegal things. There are laws against driving dirt bikes on city streets, so a police-driven city government will fixate on that rule breaking and try to stop it. They’ll bring out helicopters and raise fines and issue press releases and announce that they’ve taken important steps to improve public safety by dealing with illegal behavior.

This is a campaign against deviance. Dirt bikes don’t fit into the way the streets are supposed to work, so they’re illegal, so the police department will try to remove them and restore traffic to its normal equilibrium.

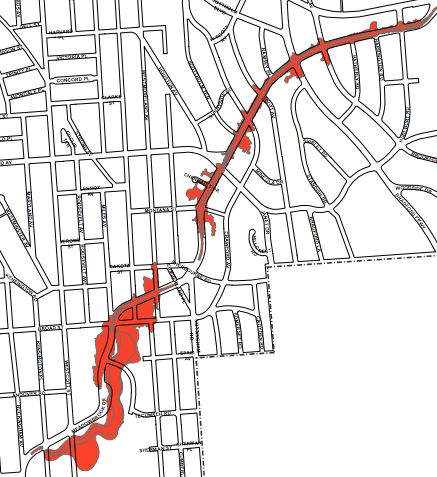

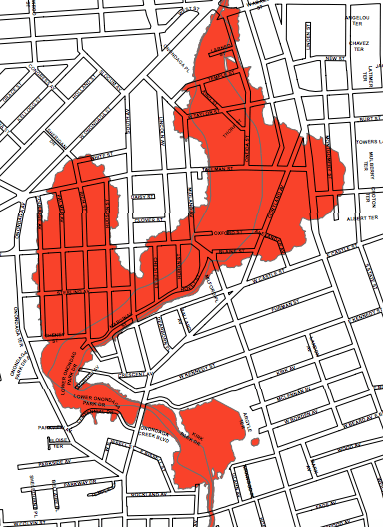

But anyone who’s experienced traffic violence knows that the normal equilibrium is really unsafe. Too large cars travelling at too fast speeds on too wide streets—it’s all extremely dangerous and it’s all perfectly legal. James Street is so deadly that City Hall’s official advice to cyclists is to avoid it, but when a car driver hit 13-year-old Zyere Jackson out front of Lincoln Middle School in 2019, SPD determined that no traffic laws had been broken.

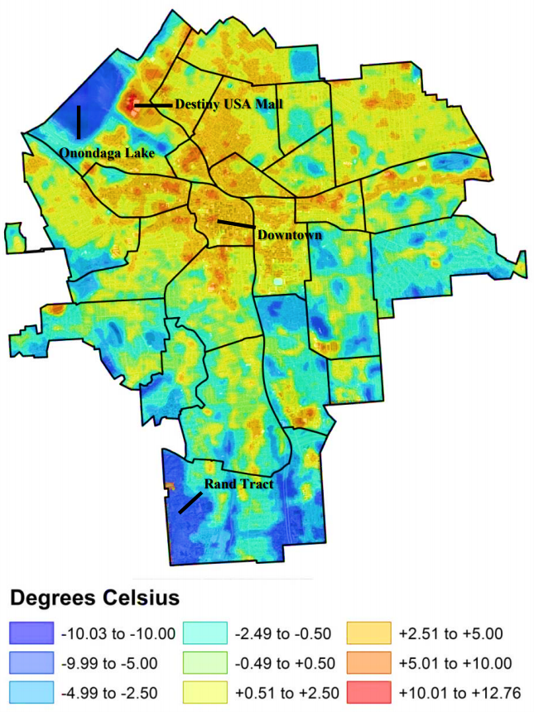

The real problem is that the streets themselves are built to be dangerous. Engineering standards governing intersection design, lane width, and signal timing all prioritize vehicle speed. The entire street network is designed and built to maximize traffic throughput at unsafe speeds, and that’s what makes the streets unsafe.

All of which is why the cities that have had the best success reducing traffic violence have focused on street design rather than law enforcement. It’s a relatively simple thing to make a street safer with curbing, textured pavement, street trees, or any other of a number of small physical alterations that lower traffic speeds and encourage everybody who uses the street to look out for each other. Those kinds of design changes make the street itself safer, and they would do more the minimize the danger from dirt bikes than increased policing can.

When the only tool you’ve got is a hammer, every problem starts to look like a nail. Syracuse turns to the SPD to solve a lot of problems, and so those problems get reduced to law-breaking. But Syracuse’s problems are more complicated than that, and they will require more comprehensive solutions. We need to invest more in municipal departments like DPW, NBD, and Parks so that they have the capacity to offer these comprehensive solutions. City Hall needs more tools to make Syracuse safer.