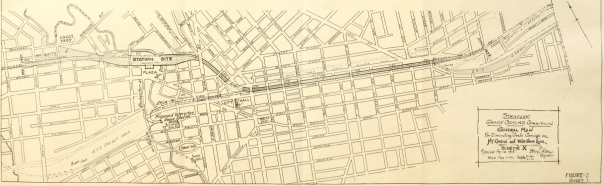

Early in the twentieth century, Syracuse was facing two huge shifts in transportation. The Erie Canal became obsolete after New York State built the Barge Canal in the Seneca River north of Onondaga Lake, and railroad traffic through Downtown had gotten so bad (158 trains a day) that the tracks had to be moved off of Washington Street. City leaders saw an opportunity to deal with both problems at once by putting the railroad tracks in the old Erie Canal bed.

What if the New York Central Railroad had moved its tracks from Washington Street to the Erie Canal bed after the Barge Canal was finished?

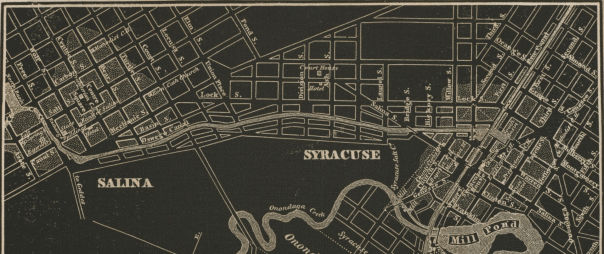

The New York Central main line entered Syracuse from the East between Burnet Avenue and the Erie Canal. It ran at grade level through that industrial valley to about Teall Avenue. There, the tracks crossed the canal and ran in the middle of Washington Street all the way through Downtown. Past West Street they passed through the rail yard between the Canal and Fayette Street, and then followed the path of the current New York, Susquehanna, and Western tracks out of town.

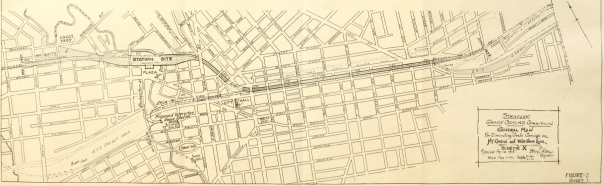

A 1917 report on grade crossing elimination proposed maintaining the line’s eastern section to Teall, turning to enter the Canal bed at Beech Street, running in that trench all the way to Montgomery Street, turning north into the Oswego Canal, and then following the path of the West Shore Railroad (present-day 690) on an elevated route out of the City. A new passenger station would go at the corner of West and W Genesee Streets, and the old station would be used for Interurban Trolleys (a precursor to Centro’s intercity coach service). That same report also recommended elevating the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western tracks along Armory Square.

What actually happened is that, in 1936, the New York Central elevated its tracks on a berm in the West Shore Railroad right of way along Burnet Ave, Noxon St, Belden Ave, and State Fair Boulevard (that embankment now supports 690 through the City), and the new passenger station went up at Erie Boulevard and Forman Ave (the current Spectrum Cable building). (The DL&W elevated its tracks in 1941, just as the earlier report proposed).

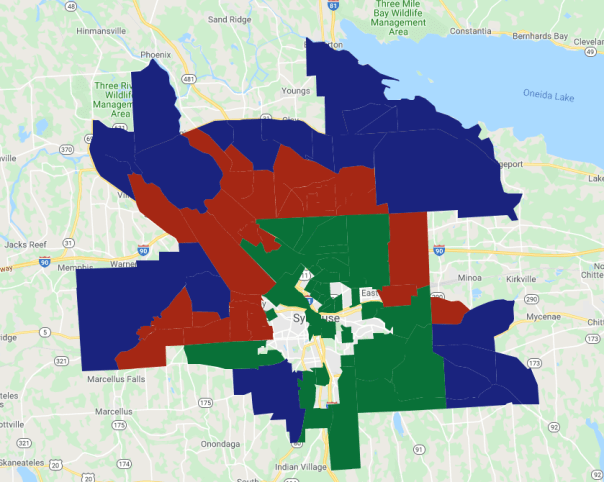

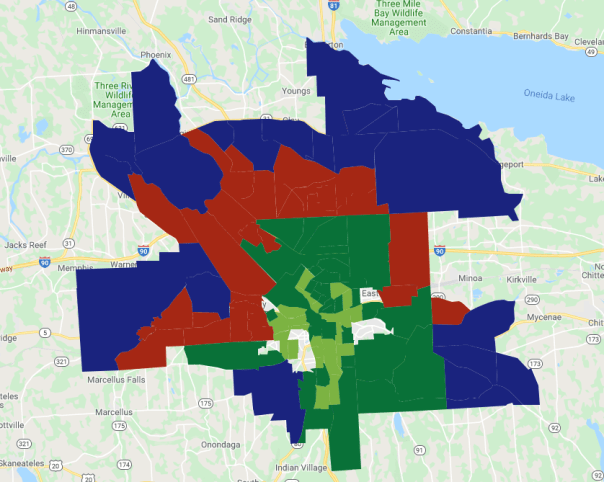

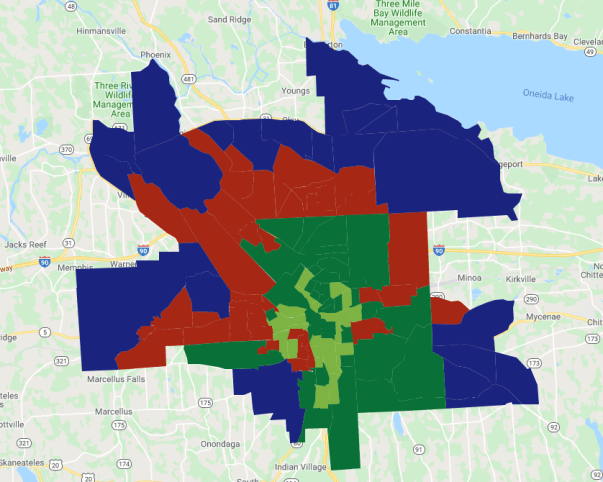

These three maps show the situation in 1917 at left, the Grade Crossing Commission’s recommendation in the middle, and the eventual 1941 elevation on the right. Red lines are train tracks at street level, blue are lines running below the streets, and green are those lines running on bridges over the streets.

Syracuse Railroads in 1917

Grade Crossing Commission’s recommendations for Syracuse Railroads in 1917

Syracuse Railroads in 1941

The difference between the Grade Crossing Commission’s recommendation and the eventual 1941 elevation amounts to moving about 1.5 miles of track 300 feet to the south and putting those tracks in a ditch instead of on a berm. It doesn’t look like that big of a switch, but it would have been huge for Syracuse’s development.

First, tracks below grade are very different from those above grade. The pictures on the left show the New York Central’s elevated line in Syracuse, and the pictures on the right show the canal bed in Rochester after that city repurposed it as a below-grade rail line. Imagine standing at the back of City Hall and being able to see into the Northside versus the situation we have now where that view is blocked by a two-story berm.

Syracuse elevated rail line

Syracuse elevated rail line and passenger station

Rochester depressed rail line in the old Erie Canal

Rochester depressed rail line in the old Erie Canal

Second, running the trains in the canal bed would have kept Erie Boulevard from becoming a major East-West crosstown route for car traffic. It’s possible that the City Planning Commission would have turned the canal into a road east of Beech Street, west of West Street, and connected those two segments with Canal or Washington Street (at the time, they were very interested in joining streets to create more crosstown routes), but it’s just as likely that another street would have taken on the role that Erie Boulevard East has come to occupy—Burnet Ave, maybe. Then, Salvation Army, Lowe’s, Price Chopper, etc. would all be in Eastwood instead of on the Eastside.

It is also possible that the canal might still run through part of the City. The main reason to fill it in was to get rid of the unreliable mechanical lift bridges that crossed it Downtown. That wouldn’t be a problem anymore if trains ran in the canal bed, some businesses did still use the canal for shipping, and cutting out the middle section would have made Erie Boulevard much less useful for getting across town, so—instead of cutting it off at Butternut Creek—the City and State might have allowed the canal to run all the way to Teall Ave or so.

Third, Syracuse would have gotten a different train station in a different place. The Grade Crossing Commission called for a new passenger station at the corner of West and W Genesee Streets. It would have sat back from the street on a new plaza at the Western edge of Downtown, and—having been designed and built in the 1920’s instead of the 1930’s—it would have been in a different architectural style from the late Art Deco station that Syracuse actually did get on Erie Boulevard outside of Downtown. That station is pictured on the left. The other pictures show some of the New York Central’s slightly earlier stations built in other New York Cities.

Syracuse’s NYC Station, 1936

Buffalo’s Central Terminal, 1929

Rochester’s NYC Station, 1914

Of course, that station plaza is now the site of the West Street interchange, and imagining a train station there raises questions about how this all would have changed the decisions that politicians and engineers made about where to put the highways.

81 could still run where it does now. It’s just worth pointing out how crazy it’d be to walk up North Salina Street with a train rumbling along below your feet while cars roared overhead.

690 is a different case. It’s built on the embankment where the New York Central elevated its trains in 1936. If the railroad had put its trains in the canal bed, then that embankment wouldn’t exist, and so 690 would have to go somewhere else.

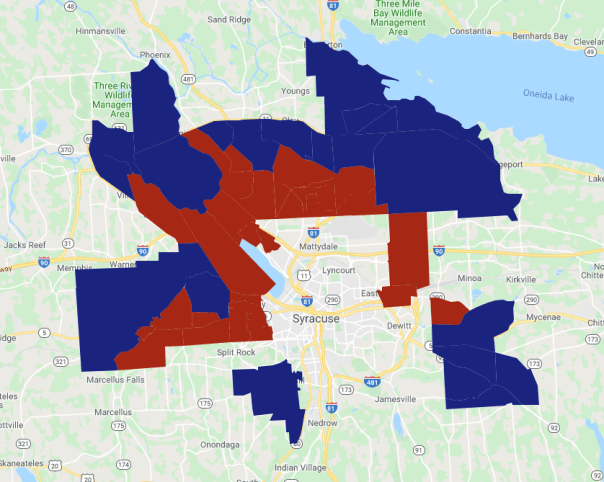

Initial plans for 690—made before NYSDOT knew that the railroad wanted to abandon its elevated track—ran the highway on a viaduct between Washington and Fayette Streets to an interchange with 81 at Almond Street. From there, the highway curved around the northern side of Downtown to follow the elevated train tracks out of the City. If the train station were at West Street, however, that route would not work. In that case, NYSDOT may have adopted a part of the City Planning Commission’s proposal to route the highway along West Street to Erie Boulevard West, and from there to State Fair Boulevard out of the City.

This would have shifted the highway several hundred feet south, covering dozens of city blocks and hundreds of acres of land—not very different from the terrible plans that NYSDOT has drawn up for rebuilding the I81 viaduct. It would have destroyed City Hall, the weighlock building, put the highways within a block of Clinton Square, and cut the train station off from Downtown.

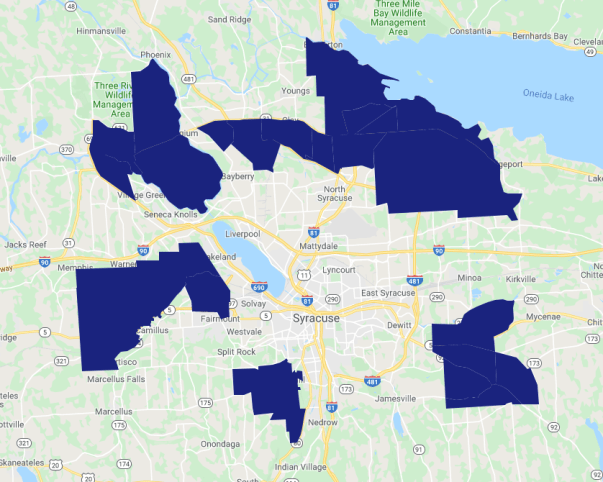

Syracuse’s railroads and highways in 2020

Syracuse’s railroads and highways in 2020 if the City had acted on the 1917 Grade Crossing Commission’s recommendations

Of course, all of these adjustments to the City’s transportation infrastructure would have had rolling implications on Syracuse’s development. What would it mean for the Westside if the Geddes Street exit from 690 was right at Fayette instead of Marquette Street? What would it mean for Eastwood if Burnet Ave had room to breath instead of being overshadowed by 690? How would Centro’s bus lines change if the train station was Downtown instead of all the way at the City’s northern edge? Would more of the factories off Carrier Circle have located on Canal Street if freight trains could still run through that valley?

For all those questions, we do know this: if they had put the trains in the canal bed after New York State built the Barge Canal, it would have shaped Syracuse very differently over the course of the twentieth century.