By Alex Lawson

Syracuse should make a bigger deal out of January 1. That’s the date of the Cook’s Coffee House Riot—the delightfully weird event that birthed the City of Syracuse.

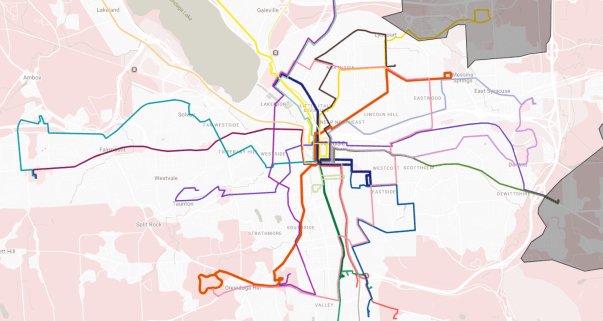

Before 1848, what we now call the City of Syracuse was a collection of independent villages. Syracuse—centered on Clinton Square—was the largest, but it was surrounded by Salina, Geddes, Lodi, and Onondaga Hollow. These little settlements jockeyed for primacy during the first fifty years or so of their existence by competing for the County Seat, the Erie Canal, the salt industry, and other markers of early American urbanism.

The Village of Syracuse’s greatest rival was Salina—the older settlement centered on Washington Square on today’s Northside. Salina was older than Syracuse and had been the earliest site of salt production, but Syracuse outgrew its northern neighbor after successfully routing the Erie Canal through Clinton Square and developing a new way to harvest local salt. Although both villages prospered through the first half of the nineteenth century, Syracuse was clearly on pace to become Onondaga County’s preeminent municipality.

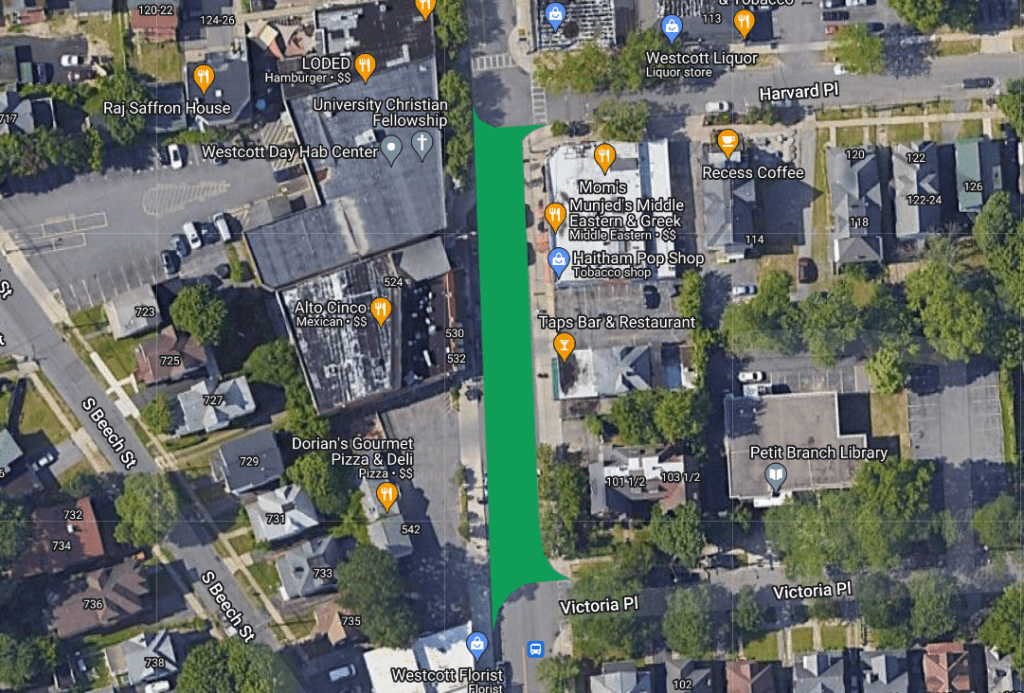

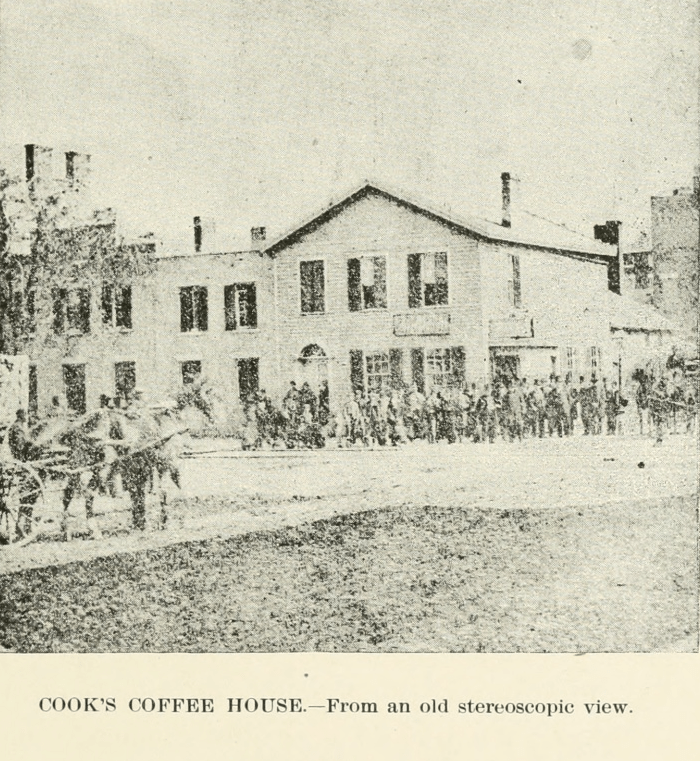

Cook’s Coffee House was located on the southeast corner of Washington and Warren Streets—the current site of Key Bank. Cook’s was a local institution with a striking interior. From a Forest to a City describes the decoration:

“[The] bar was made very attractive by placing mirrors back of the numerous decanters of liquors, and to add to the attractions was a collection of birds, the cages being hung in such a manner that every movement of the inmates was reflected in the mirrors. Chief among these attractions was a parrot whose powers of speech were most remarkable… The parrot seemed to be well informed of bar room etiquette, and he would call in the most deliberate manner for different kinds of drinks; he was cunning and mischievous, but, unfortunately, a most profane bird, and when giving utterance to his profanity the harshness of his voice was most remarkable.”

Cook’s Coffee House Riot took place during a New Year’s Ball on January 1, 1844. Several “roughs” from Salina attended the ball with the intention of picking a fight with citizens of Syracuse. The brawl escalated quickly, several people were shot—all survived—and the Sheriff called out the local militia to break it up. Although the militia arrested several people for the violence, all were acquitted the next day.

This fight was so large and so embarrassing to local leaders that it spurred a movement to merge the villages of Salina and Syracuse as a single City in order to eliminate the rivalry that had led to the riot. Syracuse received its City Charter four years later, and the new municipality encompassed the former villages of Syracuse and Salina.

The details of this story suggest a few ideas to commemorate the event. It took place on New Year’s Day—an annual holiday that already provides an excuse for festivity. A simple party is one option, or Syracuse could host a New Year’s parade like those in Philadelphia and Pasadena. A parade could trace the route of the Salina ‘roughs’ from Washington Square down North Salina Street to Downtown. Cook’s Coffee House is gone, and the bank that now occupies its site probably isn’t a good venue for a party, but the parade could end at Clinton Square or indoors at the event space in the lobby of the old Onondaga Bank. Cook’s well-documented interior suggests an obvious theme for party decorations—birds and mirrors—and the cursing parrot makes a great mascot. Any of these motifs would also work well for any bar that wants to host a New Year’s Bash or even for any private party.

As city origin stories go, Cook’s Coffee House Riot doesn’t have the mythic grandeur of Romulus and Remus or the principled optimism of Penn’s charter, but it’s fun, and it’s ours. This is the sort of story we should tell to build up a shared sense of our community’s history. And if we can throw a big party while we’re at it, that’s all the better.