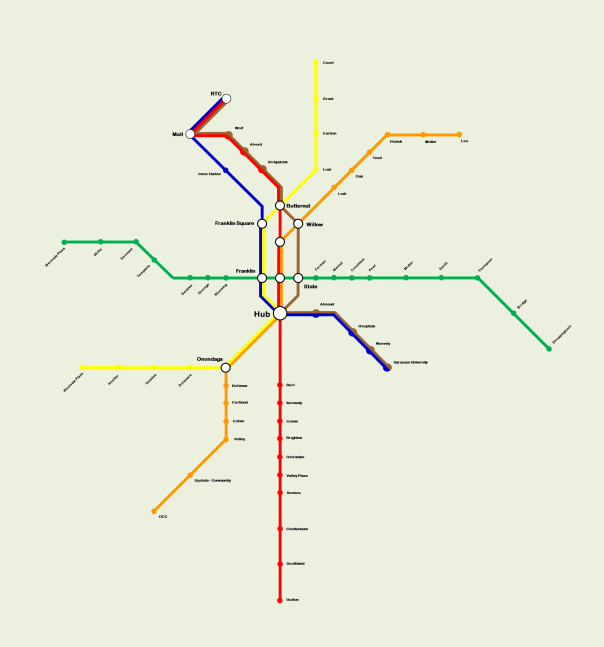

In Syracuse, most major streets lead Downtown. Salina, James, Burnet, Erie, Genesee, Fayette, Onondaga—all of them are good for getting into and out of the city center.

Most other major streets at least point towards Downtown, even if they don’t reach it. Midland, South Ave, Wolf, Court, and Butternut all end in neighborhoods outside of Downtown, but they all join up with a roughly parallel street that does reach the city center.

When so many major streets—the ones lined with businesses, the ones running through close-knit neighborhoods—lead Downtown, it makes a lot of sense to run bus lines on all of them and to make all those lines intersect at one spot Downtown at regular intervals. It’s it’s the simplest way to connect all of those different neighborhood main streets, and it’s exactly what Centro does.

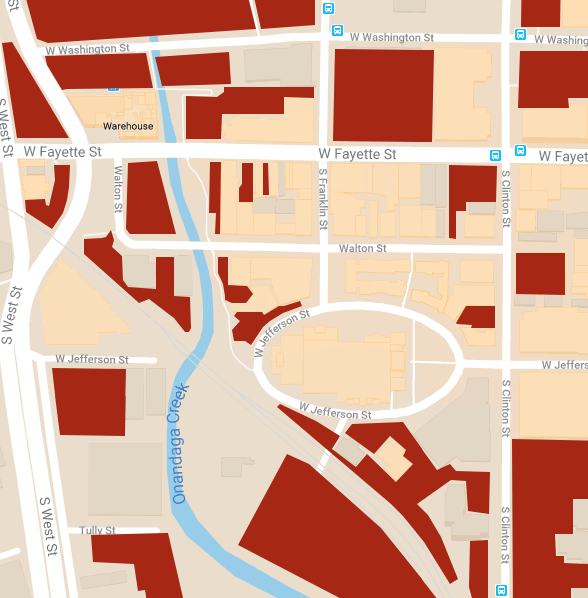

But there are plenty of major streets in Syracuse that don’t point towards Downtown at all. Brighton, Geddes, Park, Grant, Oak, Teall, and Westcott are all good streets to run a bus on, but none of them has its own line. Grant Boulevard runs from Eastwood to the train station and Mall, passing through heavily populated parts of the Northside where many people do not own cars. The 80 and 52 buses each run along Grant for a couple of blocks, but it’s impossible to get from one end of that street to the other by bus because Centro won’t run a bus line that doesn’t get its riders to the Downtown Hub.

The result bad for bus riders in two ways. Buses like the 80 and 52 try to do two contradictory things (go Downtown and serve Grant Boulevard), and they end up doing neither very well. If you’re taking one of these buses to Downtown, then those zigs and zags that it makes on parts of Grant (and also Park Street) are a waste of your time.

At the same time, riders can’t actually use these buses to get along a street like Grant. This makes it really inconvenient to get between two points on one side of town—between Eastwood and Westcott, say, or between Grant Village and the Mall—because you have to go all the way Downtown to make the transfer.

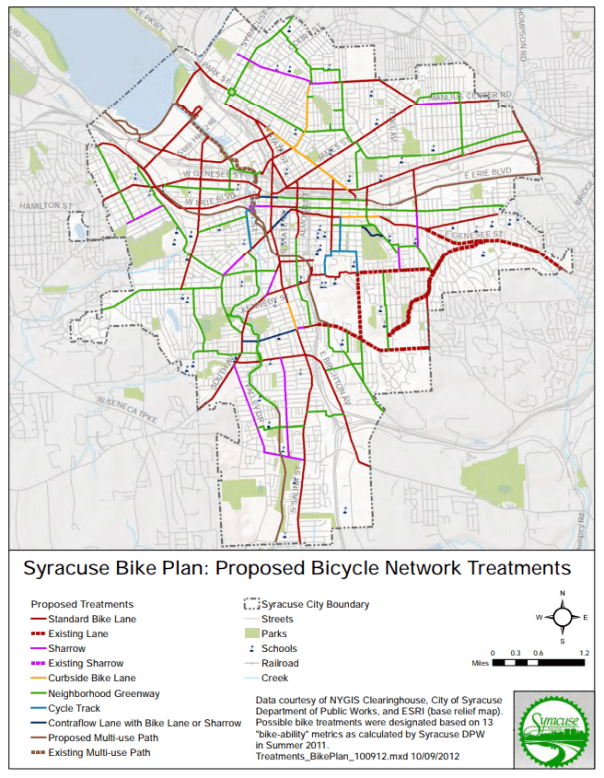

Centro could fix both problems with new bus lines that follow these streets without ever trying to get downtown. Taking Centro’s existing jogs and deviations as a starting point, here are some potential crosstown lines that never go Downtown.

These bus lines (or ones like them) would make it much easier to get around town. That’s obviously true if you’re traveling along one of these lines (from Skunk City to the Mall, say), but it’s also true for people transferring between two lines. Imagine trying to get from the corner of Colvin and Salina to OCC. Currently, you’d have to ride more than a mile north (away from where you’re going) to connect with the South Ave bus that will take you to OCC. The full trip is 5.5 miles. If there were a bus running East-West on Brighton, though, you could walk ⅓ mile to catch it, ride west to South Ave, connect to the OCC bus there, and reach campus in less than 3.5 miles.

At the same time, these lines would make the Centro’s existing lines more useful by allowing them to run in straight lines. Some James Street buses take an extra 12 minutes to get Downtown because they detour along Teall. A bus running along Teall from Lyncourt to Westcott would eliminate the need for that detour and make Centro’s James Street service faster, more efficient, and more useful to people actually trying to get Downtown.

Right now, Centro is trying to “fill in service gaps” with some money that it just got from New York State. The most egregious gaps in Syracuse’s bus service are temporal—even the busiest lines have service gaps that last more than an hour during the middle of the day—and Centro needs to fill them first.

The next gaps that need filling are the ones on Brighton, Teall, Westcott, Geddes, Grant, Bellevue. Crosstown bus lines on those streets would make it easier, faster, and simpler to get around Syracuse by bus. Combined with the SMTC’s planned BRT service, these new lines would make it easy to live in Syracuse without a car.