On May 15, Syracuse University published its Campus Framework. This document “is meant to guide future potential development and decision-making” on both the University’s “physical campus and the surrounding area” until 2037. The plans for the campus’ “surrounding area” will have a direct impact on the City’s Near Eastside.

The last forty years show how Syracuse University’s building programs can either help or hurt the neighborhoods that abut the campus. During the 1970s and 80s–a period that the Framework calls “Strategic Investment”–Syracuse University closed public streets on University Hill and built new dorms on South Campus in order to remove students as much as possible from the City. The most visible project from this period is Bird Library, a concrete bunker built on top of what had been a public park and which cut off the intersection of Walnut Avenue and University Place.

Euphemistically, the Framework describes all of this building as “introspective”–it was really just an attempt to wall the campus off from the City. As the University separated its campus from the surrounding neighborhoods, it also discouraged students from living in city communities and contributing to their well-being. This ‘introspection’ added to the City’s myriad problems during these decades.

From the 1990s until 2014–a period that the Framework calls “Campus + City”–Syracuse University outgrew the wall that it had built along Waverly Avenue, and it had to locate new facilities further and further from the insular campus quad. Eventually, the University complemented this physical expansion with new services and initiatives that benefited both students and city residents. The most visible project from this period is the Connective Corridor, a free public bus route running from a university building in Armory Square to the main campus on University Hill.

Practical and economic factors forced the University to expand and expose itself to the City, but programs like the Connective Corridor, the Near Westside Initiative, and Say Yes to Education had a genuine positive impact on the community. Nancy Cantor, the University Chancellor who drove much of this new development, saw the University as an ‘Anchor Institution’ that could provide employment, capital, philanthropy, and a community vision for the City of Syracuse. She understood that city problems, if left unsolved, could eventually become university problems, so it was in the University’s interest to work for the benefit of the entire community. The two would succeed or fail together.

The Framework proposes to meld the ideas that guided campus development during these two periods. Like the “Campus + City” period, it looks for space to grow beyond the campus’ traditional boundaries, but like the “Strategic Investment” period, it seeks to draw a line between that new growth and the surrounding neighborhoods. The next period of campus development–which the Framework calls “Campus-City”–is ambivalent about about the University’s relationship to the City, but it should ultimately benefit the neighborhoods that surround the redeveloped campus.

According to the Framework, the chief challenge of the Campus-City period will be to consolidate the physical expansion of the Campus + City period while regaining the insular feeling achieved during the Strategic Investment period:

Syracuse University’s close physical connection to the city is an asset for partnerships and campus vibrancy; yet, it also creates challenges for an identifiable, clear sense of campus arrival. While the historic Campus on the Hill occupies a clearly defined area south of the Einhorn Family Walk, the University’s many other buildings within the Campus-City Community are not clearly defined.

It’s not enough that university buildings stretch down the northern slope of University Hill–those individual buildings must create a “clearly defined area” that campus visitors can enter or exit through “gateways.” That area’s definition should consist of “strong architectural design” communicating “University presence” and achieved through renovation of existing buildings and redevelopment of underused land.

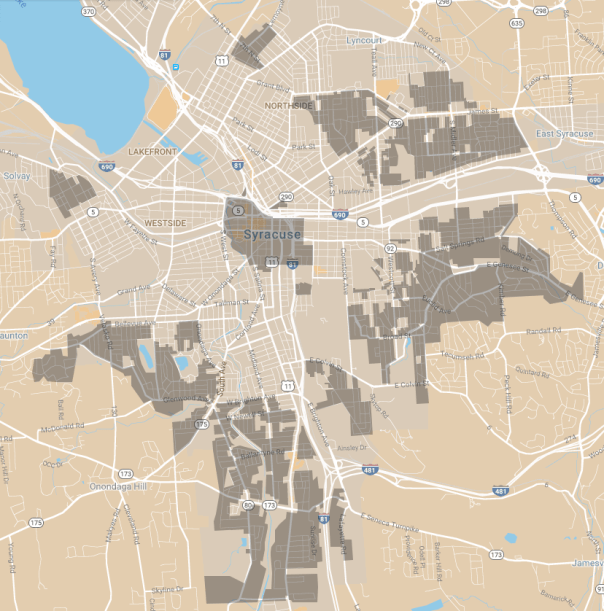

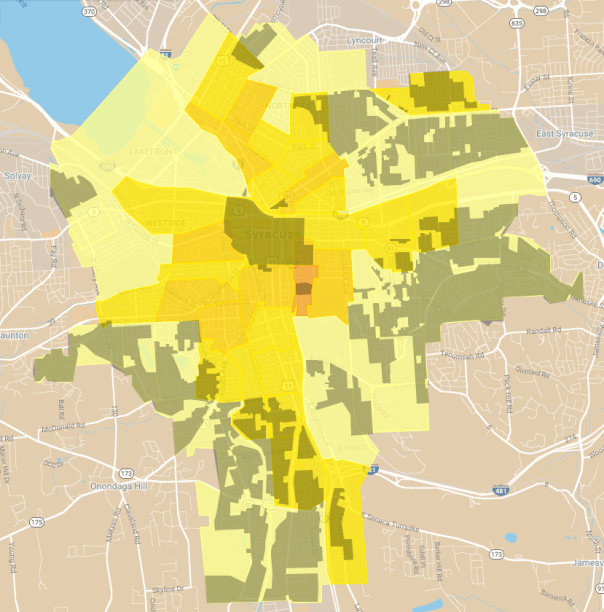

The northern slope of University Hill lacks definition because it’s covered with surface parking. The University owns many of these lots, and the Framework proposes that it construct new dormitories on most of them. By designing these buildings all at once, the University can unify their facades and extend the campus’ clearly defined area all the way north to Harrison Street.

There is an economic incentive here as well. The University is in some financial trouble, and it can’t afford to keep buying up more land every time it needs to construct a new building. By more fully developing the land that it already owns, the University can add thousands of square feet of classroom and residential space without purchasing any more real estate.

Despite the insularity inherent in any plan to create “gateways” (entrances that imply barriers), this plan should benefit the neighborhood north of Harrison Street. First, by moving all of the dorm space from South Campus to University Hill, the University will bring an enormous buying population within walking distance of a struggling retail market. That will support the businesses along Genesee and Fayette Streets, and it will draw new businesses to the neighborhood, putting more daily errands and jobs within walking distance for the people who already live there.

Second, the decision not to buy any more land means that the University will not actively displace nearby residents. The majority of people living in the neighborhood rent their homes, so they’d be particularly vulnerable if the University continued to buy up land. This also means that there will be less total demand for land in the surrounding neighborhoods, and that will keep rents down.

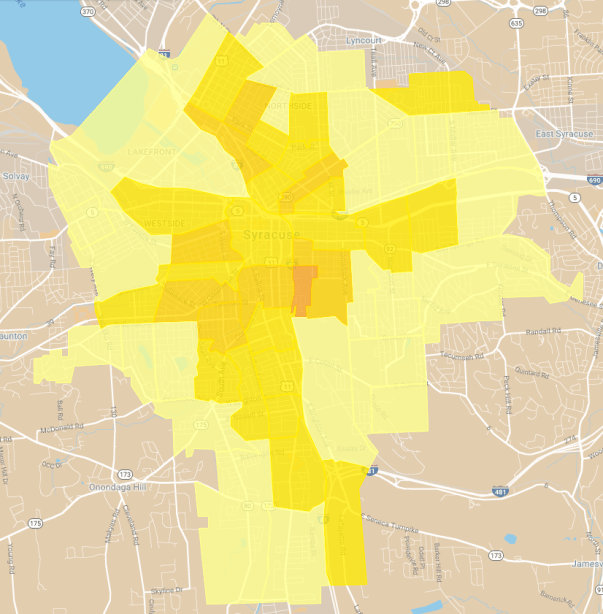

Third, the Framework’s proposed upgrades to the Centro system will benefit everybody who rides the bus. After the University helps Centro implement the technology necessary to support “Real-Time Bus Arrival Information” and a “Bus Locator App,” Centro can turn around and offer those services to all of its riders. The Framework also proposes “Free Centro” for students–a subsidy that would boost ridership figures and automatically increase Centro’s state aid under the State Transit Operating Assistance funding formula.

Local government has work to do to capitalize on this opportunity. Just like the Strategic Investment period, the University still wants to control the public spaces within its campus. These include streets like University Place–long closed to through traffic and recently turned into a footpath–and parks like Walnut Park–a quarter of which is covered up by Bird Library, and which the Framework discusses as if it belongs to the University. City Hall needs to hold the line and keep public spaces public. That makes the difference between an insular campus and a Forbidden City on University Hill.

The State or SUNY Upstate or whoever it is that’s responsible also needs to let go of the land where Kennedy Square used to stand. The original plan for the site–displacing poor families in order to build a state-run luxury “neighborhood”–was bad, and it probably won’t ever get built. The land has sat vacant for four years, but developers are building new apartments along its edges. To more equitably distribute the benefits of land ownership, the State should allow City Hall to subdivide that land into normal-sized lots, and then it should sell those lots off to private developers who can build apartment buildings, stacked flats, single family homes, office buildings, and retail space on this prime real estate between the University and Downtown Syracuse.

The Westcott Neighborhood enjoys all kinds of advantages because of its proximity to Syracuse University. Students and professors live alongside families without any formal relationship to the University. Between subsidized apartments, cheap apartments, luxury apartments, affordable houses, and expensive houses, rich people and poor people all can find a place to live. The neighborhood has good transit, two grocery stores, and an active business district, allowing people to meet their daily needs without owning a car. It’s a place where all kinds of different people can make a good life.

The plans described in the Framework can bring the same benefits to the neighborhood north of Harrison Street. For all of its abstract discussion of architectural definition and efficient land use, the plan amounts to this: the University will move a lot of student housing from South Campus to the parking lots along the main campus’ northern fringe. That will instantly increase the area’s population without driving up its rents, and that means more money circulating through the neighborhood. If City and State government handle this change well, the result will be a larger, denser, healthier neighborhood between University Hill and Downtown Syracuse.

The University is asking for comments from the on the Framework. You can submit them at this link.