With all the new apartment buildings going up on Syracuse’s Eastside, it seemed like a fluke that one planned for Westcott Street never got past the drawing board. It wasn’t. That apartment building didn’t get built because of exclusionary zoning policies that prohibit new housing in some places and concentrate it in others. As Syracuse grows, that imbalance will push people looking for housing into certain neighborhoods, driving up rents, gentrifying them, and displacing current residents. ReZone—City Hall’s comprehensive rewrite of the City’s zoning ordinance—is a once-in-a-generation chance to prevent this by creating housing opportunity in more city neighborhoods. That’s a chance City Hall needs to take.

City Hall enacts exclusionary zoning policies when vocal neighborhood groups like UNPA pressure it to do so. Those exclusionary policies—minimum lot sizes, required setbacks, limits on multi-family housing, parking requirements—make it difficult or impossible to build new housing in a neighborhood. The Westcott Street project—one that would have added 32 middle-income apartments to this well-off neighborhood—ran afoul of all of these.

Meanwhile, about a mile away on Genesee Street, three enormous new buildings are adding hundreds of new apartments to the foot of University Hill. Each of those buildings is much larger than what had been planned for Westcott Street, but they’re going up without much of a fight. That’s because Genesee Street is already zoned to allow apartment buildings by right—something that wouldn’t be true if a powerful neighborhood association like UNPA was guarding that land. In fact, there is no neighborhood association worrying about what all that new housing will do to Genesee Street’s ‘character’ because there are hardly any people living near that part of Genesee at all.

For now, this works. People in Westcott get to keep their neighborhood to themselves, people looking for a place to live can move to Genesee Street, and everybody who relies on municipal services benefits from the new tax revenue. The same thing is happening across the City where the zoning is lax and there aren’t enough existing residents to block new residential construction—Franklin Square, East Brighton, University Hill, the Inner Harbor, and even Downtown. All that empty space has been a safety valve, allowing developers to build and market new housing without putting pressure on existing neighborhoods.

But Syracuse is running out of empty space. Three recent projects turned old factories into new apartments in established residential neighborhoods on the Westside. This month, City Hall and the Allyn Foundation announced that they want to build hundreds of new homes on land currently occupied by public housing on the Southside.

New housing is not a bad thing. Too many older homes in Syracuse are poorly insulated, have roofs that leak, are painted with lead. New housing of good quality is an opportunity for current residents to live somewhere better. Similarly, too many older neighborhoods in Syracuse don’t have enough people. New neighbors pay taxes, shop at local businesses, bring up property values, and increase the neighborhood’s political power.

The problem is that limited supply and geographic concentration mean that a lot of this new housing isn’t affordable for the people who already live in the neighborhoods where it’s being built. Developers can’t build much new housing at all, so they’re pricing and marketing what little is allowed to attract the small pool of tenants who can pay $1,385 for a 1-br in the Dietz Lofts, say. That’s more than twice the median gross rent of the Westside neighborhood where the Dietz building sits—a neighborhood where half of tenants spend more than 30% of their monthly income on rent.

Converting empty factory buildings into expensive apartments won’t displace anybody, but the same zoning laws that made the Dietz Lofts possible also allow property owners to convert existing 1-family homes into multi-family apartments. The same economic pressure that set the Dietz’ rent at $1,385 will do the same to any newly renovated duplex. That will displace people.

People have to live somewhere, and developers are building new homes for them where it’s easiest—where the zoning already allows it. Because some neighborhood groups have been so successful at redrawing the City’s zoning map to exclude new residential construction, it’s concentrated in a select few neighborhoods. Because developers will always go after the highest rents first, they’re building homes that are often unaffordable for the people who already live in those neighborhoods. This is how exclusionary zoning in some neighborhoods causes gentrification in other neighborhoods.

Syracuse’s zoning map controls the supply and geographic concentration of housing in the City. City Hall needs to amend that map to allow more housing in more neighborhoods. City Hall needs to make those changes now—before Syracuse runs out of empty land for new residential development—in order to get ahead of the economic trends that have led to rising rents, displacement, and housing crises in other cities.

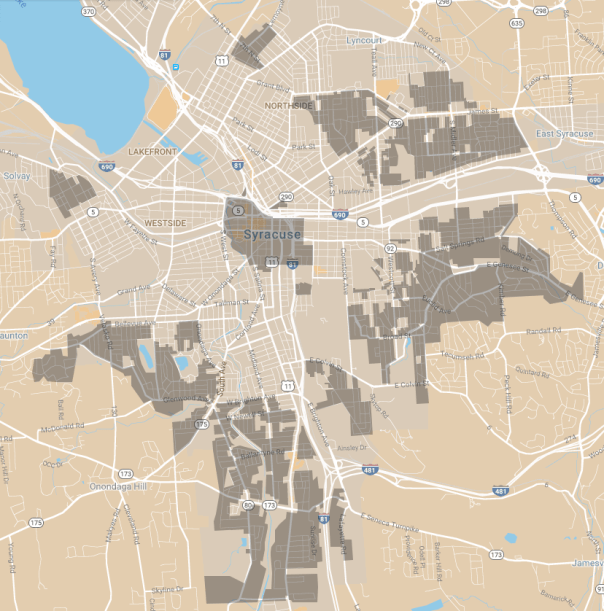

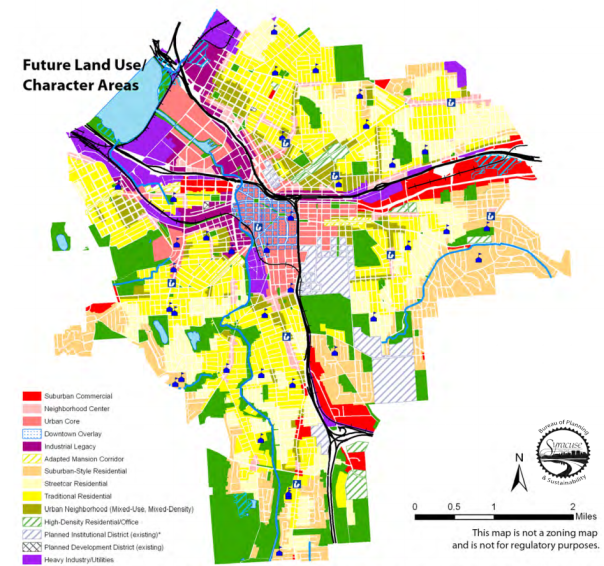

ReZone provides the opportunity to do just that. City Hall’s Land Use & Development Plan—the document that’s supposed to guide the ReZone project—contained a map that showed how to disperse new residential development and population growth across many city neighborhoods. It recommended zoning to allow 1 and 2-family homes (shaded bright yellow) in almost all of Westcott, the Northside, the Southside, the Westside, and in half of Eastwood. It recommended zoning to allow bigger apartment buildings (shaded olive green, magenta, and pink) along neighborhood main streets and in parts of all those same neighborhoods. If Syracuse was zoned this way now, that Westcott Street apartment building could have been built.

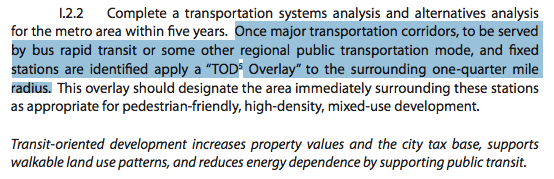

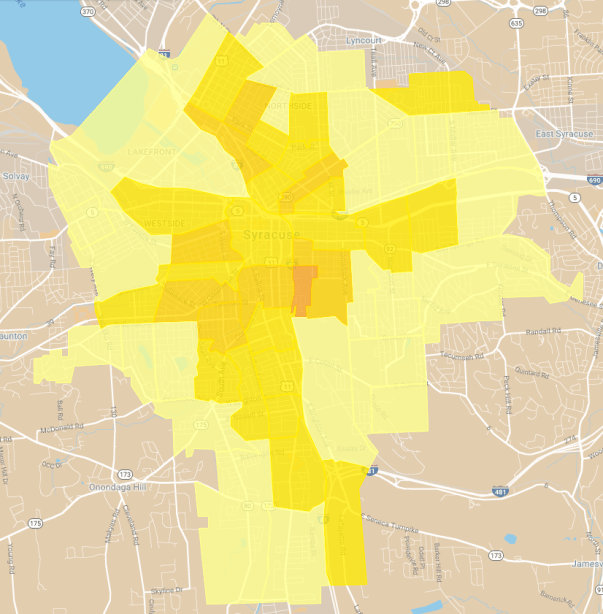

ReZone is now on its third draft zoning map. The first draft (February 2017) followed the LUDP’s recommendations to allow new residential construction in most city neighborhoods with three unfortunate exceptions. First, the February 2017 draft zoning map all but banned multi-family housing from Eastwood outside of James Street itself. Second, it significantly reduced the amount of multi-family housing that could be built in Westcott. Third, it significantly increased the amount of multi-family housing allowed on the South and West sides, particularly in an area where Onondaga Creek regularly floods.

Since that February 2017 draft, it’s only gotten worse. From the Northside, to Tipperary Hill, to Lincoln Square, each successive draft has limited the amount of housing that can go into certain Syracuse neighborhoods, effectively funneling future population growth into a select few others with predictable negative consequences. (Lots shaded yellow are zoned to exclude new apartment buildings).

Syracuse needs people. It needs for kids to grow up and make their lives here, and it needs for people to move in from out of town. It needs these people to pay taxes, ride buses, shop at local businesses, attend PTA meetings, vote, and invest in the community.

And those people need a place to live. As it stands, they’re going to have a hard time moving into some neighborhoods where exclusionary zoning policies have artificially limited their access to housing opportunity, and they’ll have an easier time moving into other neighborhoods where their presence will, at least in the short term, be a hardship on their new neighbors.

It shouldn’t be this way. That 32-unit apartment building should go up on that Westcott Street parking lot, and a few dozen people should be able to choose to live there, lowering demand for new housing in other neighborhoods and spreading out the effects of new residential development and population growth across the entire City. That’s the only way to equitably harness the population growth that Syracuse needs and ensure that it benefits everybody who lives in the City.