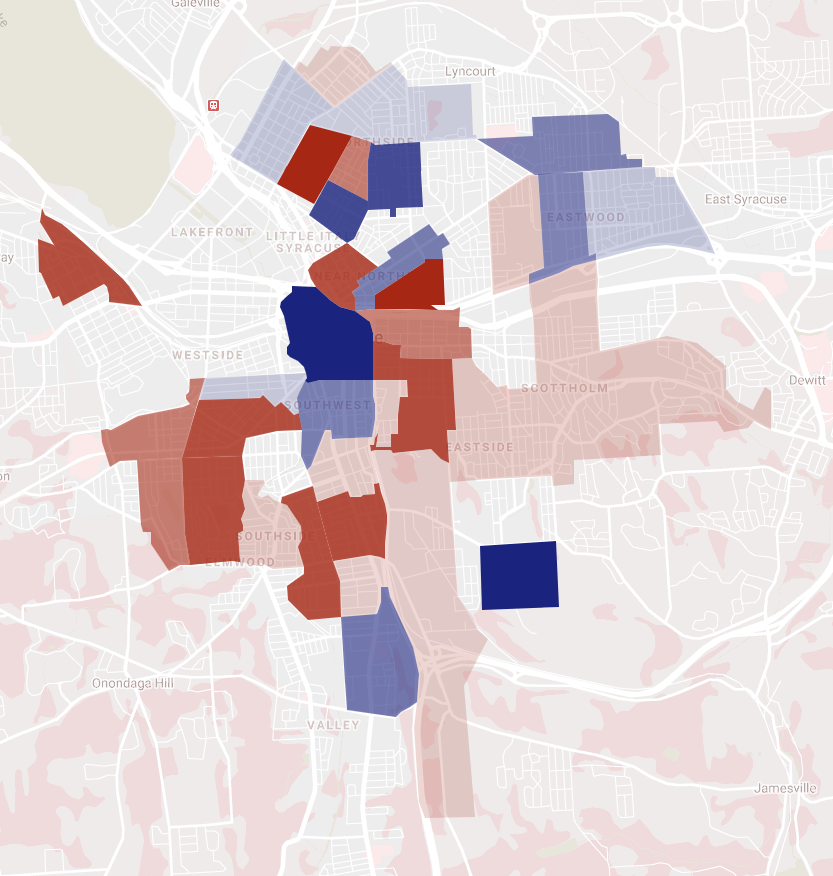

81, 690, and the West Street Arterial are designed to make Downtown more accessible from the suburbs, but they’re also designed to make Downtown less accessible to city residents.

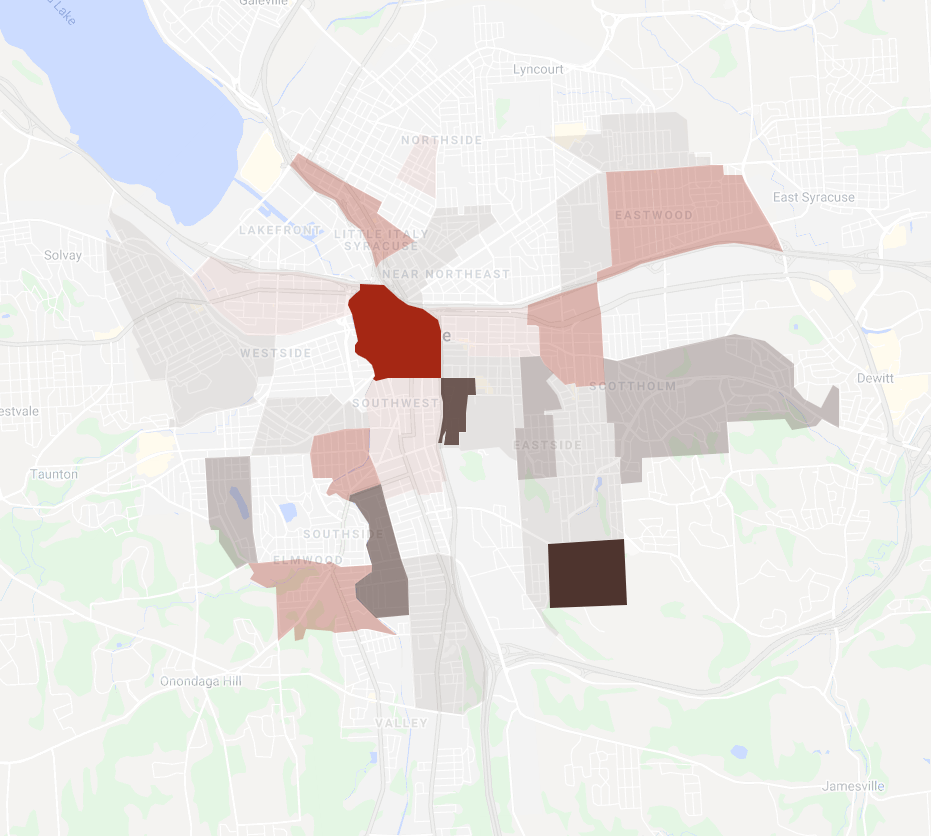

They do this in two ways. The first is to cut off local streets that connect adjacent neighborhoods. 81—and the urban renewal projects that went with it—closed Jefferson, Cedar, Madison, Montgomery, and McBride Streets. The interchange with 690 closed Oswego Boulevard and Pearl and Canal Streets. The West Street Arterial closed Belden Avenue and Walton Street, and it severed Marcellus, Otisco, and Tully Streets from their connection to Downtown too.

The second is to funnel so much vehicular traffic onto the remaining streets that they become unusable to anybody not in a car. This is the state of Harrison and Adams most obviously, but it’s also a problem on Fayette, Genesee, and Erie Boulevard. A car driver approaching from the East used to have 11 different options for entering Downtown—now there are only 6. These remaining swollen streets are awful to walk along, difficult to cross, and impossible to bike in, so they crowd out local foot traffic between adjacent neighborhoods.

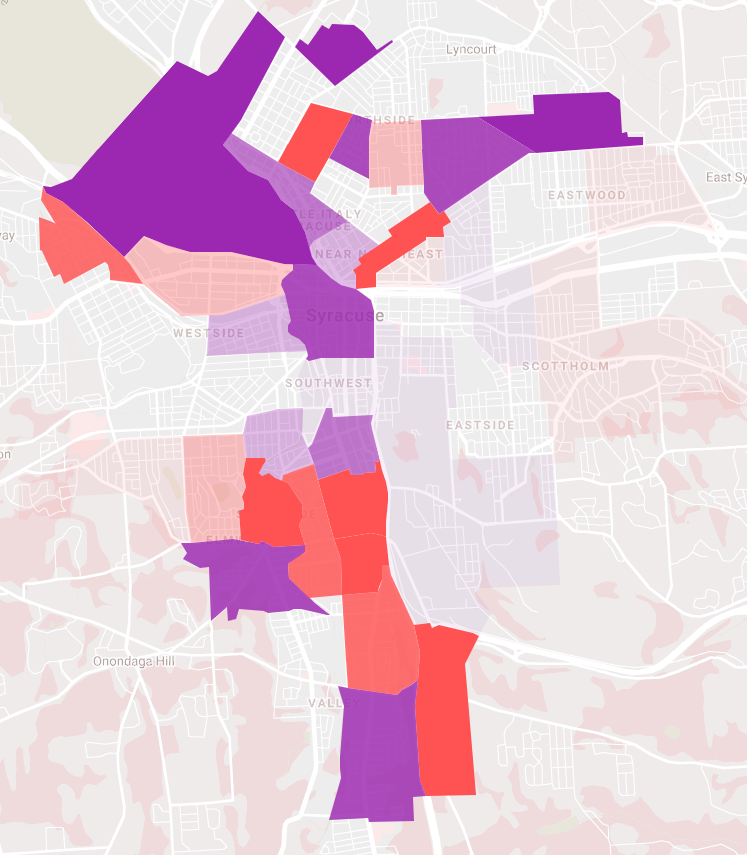

Any plan to fix that damage has to do more than just remove the highway—it also has to break down the barriers that segregate neighborhoods by establishing new connections between them.

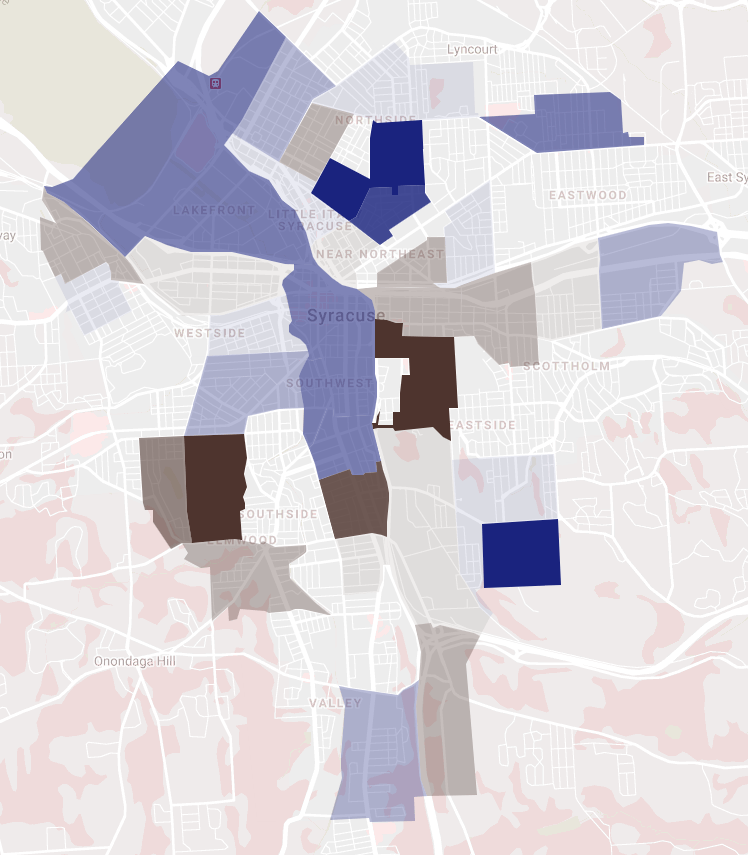

reopened streets at Downtown’s northern edge

safe crosswalks at Almond and Washington Streets

NYSDOT’s plan for the Grid does this a little bit. It reopens streets like Pearl and Oswego Boulevard, expands the Creekwalk, adds a few blocks of bike lanes, and shortens crosswalks at major intersections.

But those are just starts. Syracuse needs a more comprehensive plan to reconnect Downtown to the City. That will mean adding low-traffic pedestrian-friendly connections—like a bridge over Onondaga Creek at Fabius or opening footpaths through Presidential Plaza. It will mean narrowing West and Adams so that people can walk across them safely. It will mean building a functional public transportation system.

It should not be easier, cheaper, and more convenient for a person from Van Buren to drive Downtown than it is for someone from Park Avenue to walk Downtown. It shouldn’t be that way for no other reason than that Van Buren is 10 miles from Clinton Square while Park Avenue is less than a mile away. We’ve successfully warped the County’s geography so that 10 miles seems like less than 1, but we did it by building a wall between Downtown and the surrounding City neighborhoods. It’s time to tear that wall down and reestablish the City’s connection to its center.