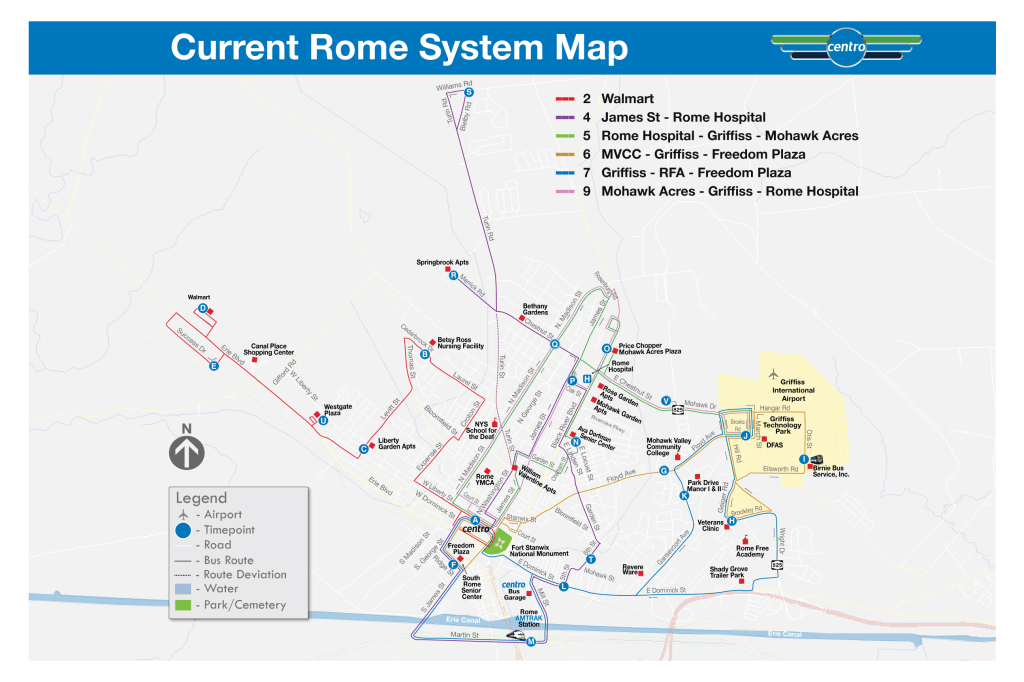

Centro’s newly announced service update for Rome offers a glimpse of how the transit authority might improve service in Syracuse. Rome’s new network features higher service frequencies on high-ridership routes, a clockface timetable, and on-demand service to cover lower-ridership areas.

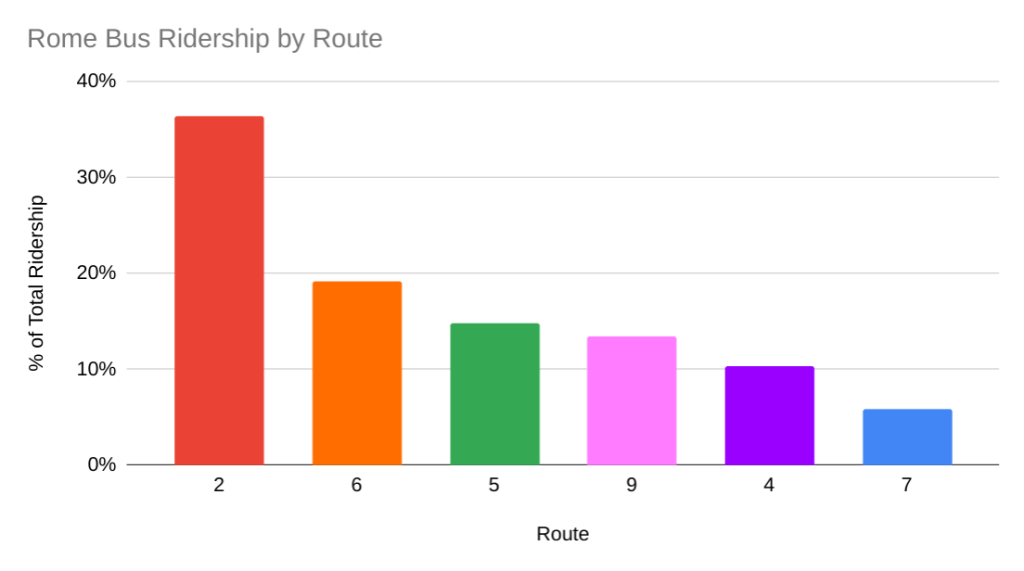

Centro currently runs six bus lines in Rome. The routes with the highest ridership (accounting for more than half of all trips in the network) are the 2 and 6 buses. The next two highest performing lines (providing more than 1 out of every 4 rides) are the 5 and 9 buses. The two lowest performing routes (carrying fewer than 1 of every 6 passengers) are the 4 and 7 buses.

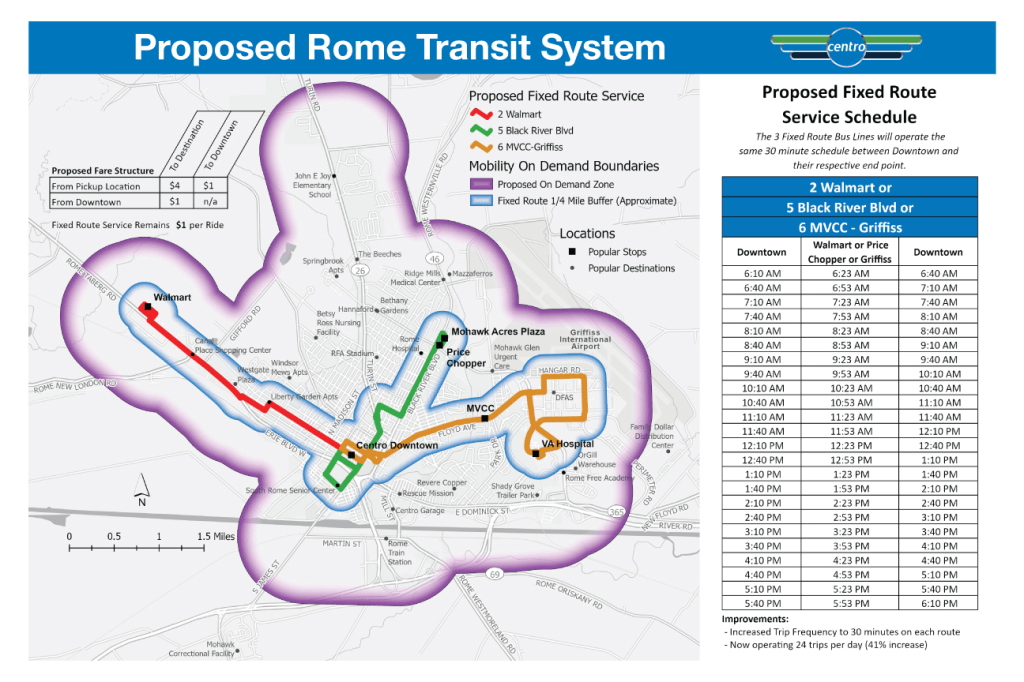

Under the new network, Centro will increase service frequency on the high-performing 2 and 6 buses by a whopping 41%. The 5 and 9 buses will also see a comparable service increase, although they will be combined as a single route.

These service improvements are also service simplifications. Centro’s current Rome schedules don’t follow a regular pattern—different buses run at different times of day, and headways range from 30 to 90 minutes depending on the route and run. That all makes it difficult to use the system without consulting the schedule.

The new timetable will be identical for all three lines, and it will run on regular 30-minute ‘clockface’ intervals all day. This makes it much easier to memorize each bus route’s schedule—they all leave Downtown at 10 and 40 minutes past the hour.

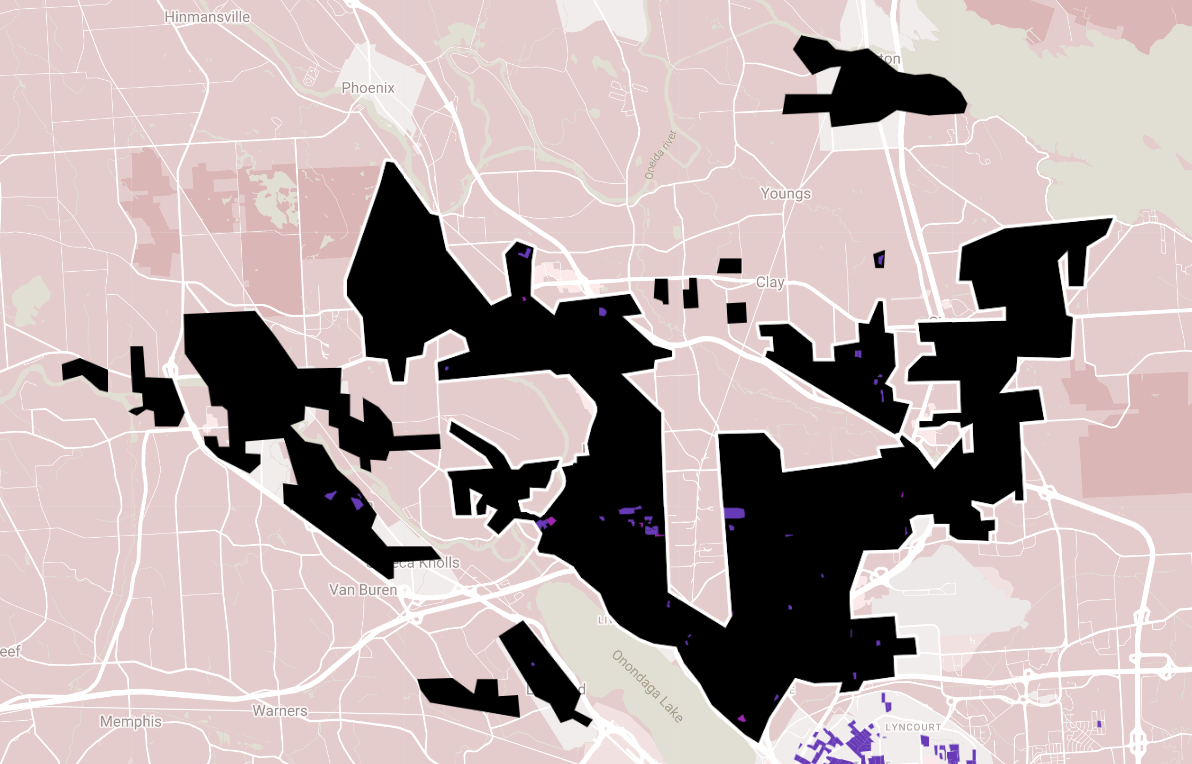

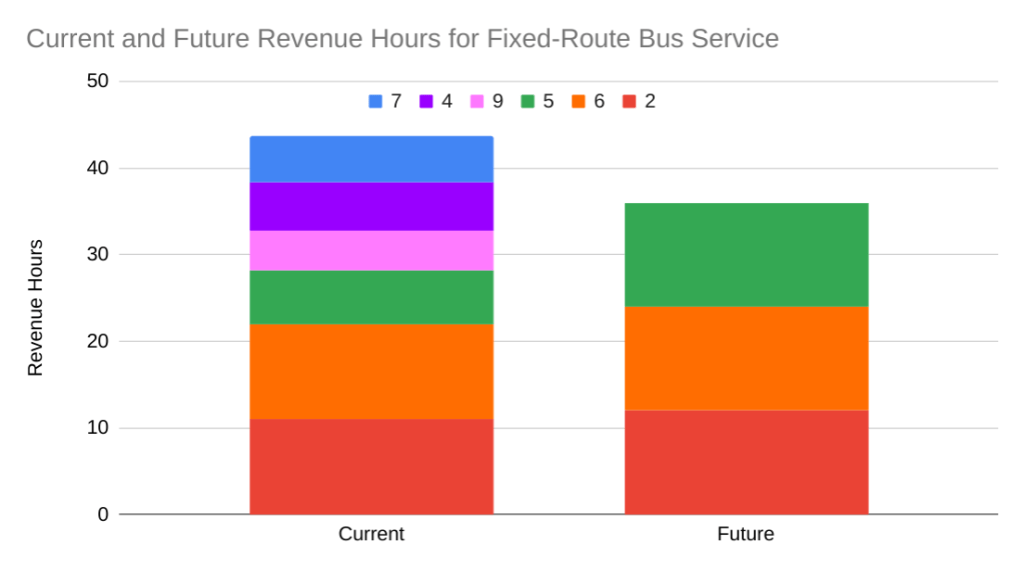

In order to provide all of this new service on high-ridership routes with existing resources, Centro is cutting fixed-route service from some low-ridership areas. The 2, 5, 6, and 9 buses are losing some of the zigs and zags that allow them to cover a greater area at the expense of speed. In the new network, these routes will run in straight lines, and buses will be able to complete each run in 30 minutes (compared to 40 minutes today). Centro is also cutting the 4 and 7 buses entirely.

Together, these changes will reduce fixed-route revenue hours (a major driver of operating costs) by 18% even as Centro increases service frequency on remaining bus lines. Those operating savings will fund a new on-demand service in areas losing fixed-route service. This new on-demand service will likely be similar to Uber pool, where riders request a ride via phone or an app, and Centro will dispatch a jitney-style vehicle to pick up multiple riders traveling in the same direction.

We still have to see how this plan works in practice. ‘Low-ridership’ areas might see a lot more demand after their spotty bus service gets replaced with a subsidized taxi. In that case, Centro will either have to divert more resources to its on-demand service—reducing or eliminating the projected cost savings that are supposed to make higher bus frequencies possible—raise the on-demand fare, or riders will have to deal with longer wait times for pickup.

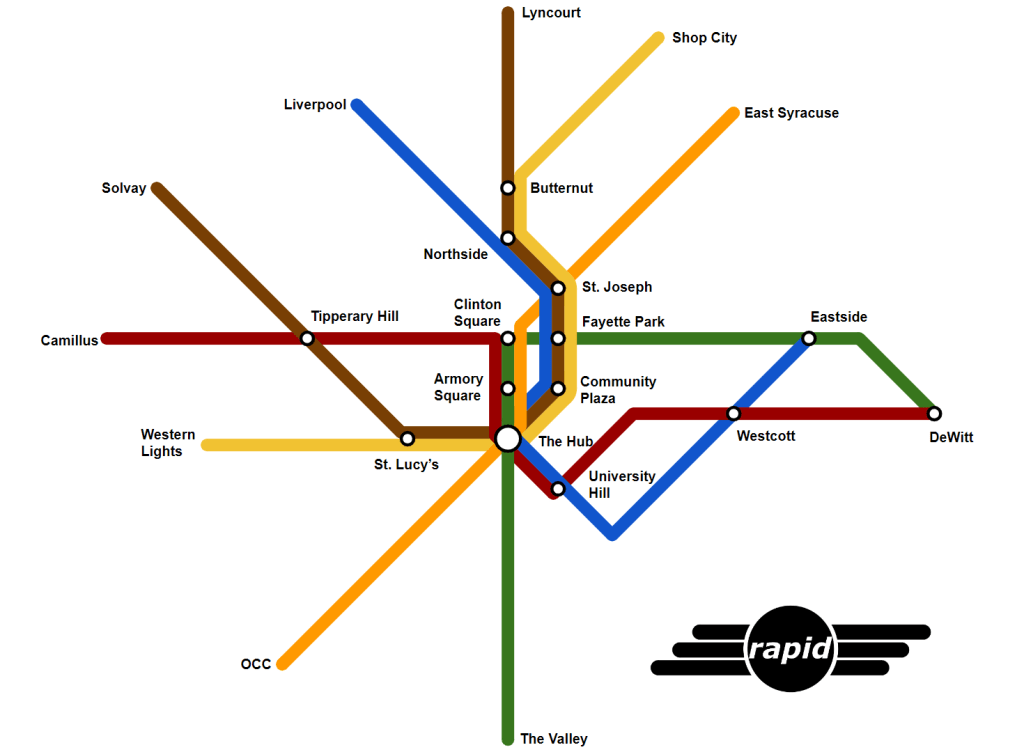

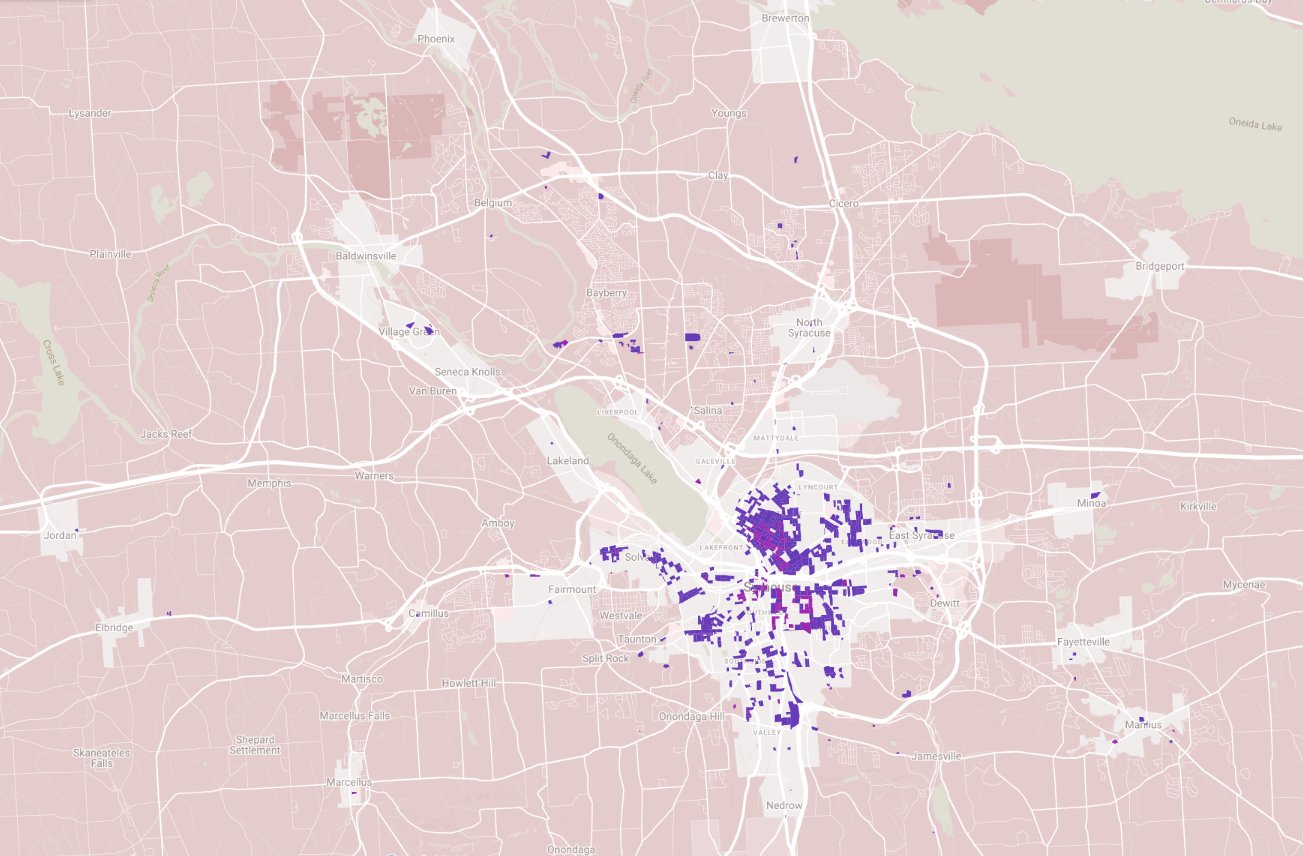

But if Centro can manage that balance, this new service model can make a big difference in Rome, and it should be applied to Syracuse. The model’s principles—prioritizing high-frequency service on direct bus routes running through high-ridership areas—are exactly what planners and advocates have pushed for in Syracuse for years.