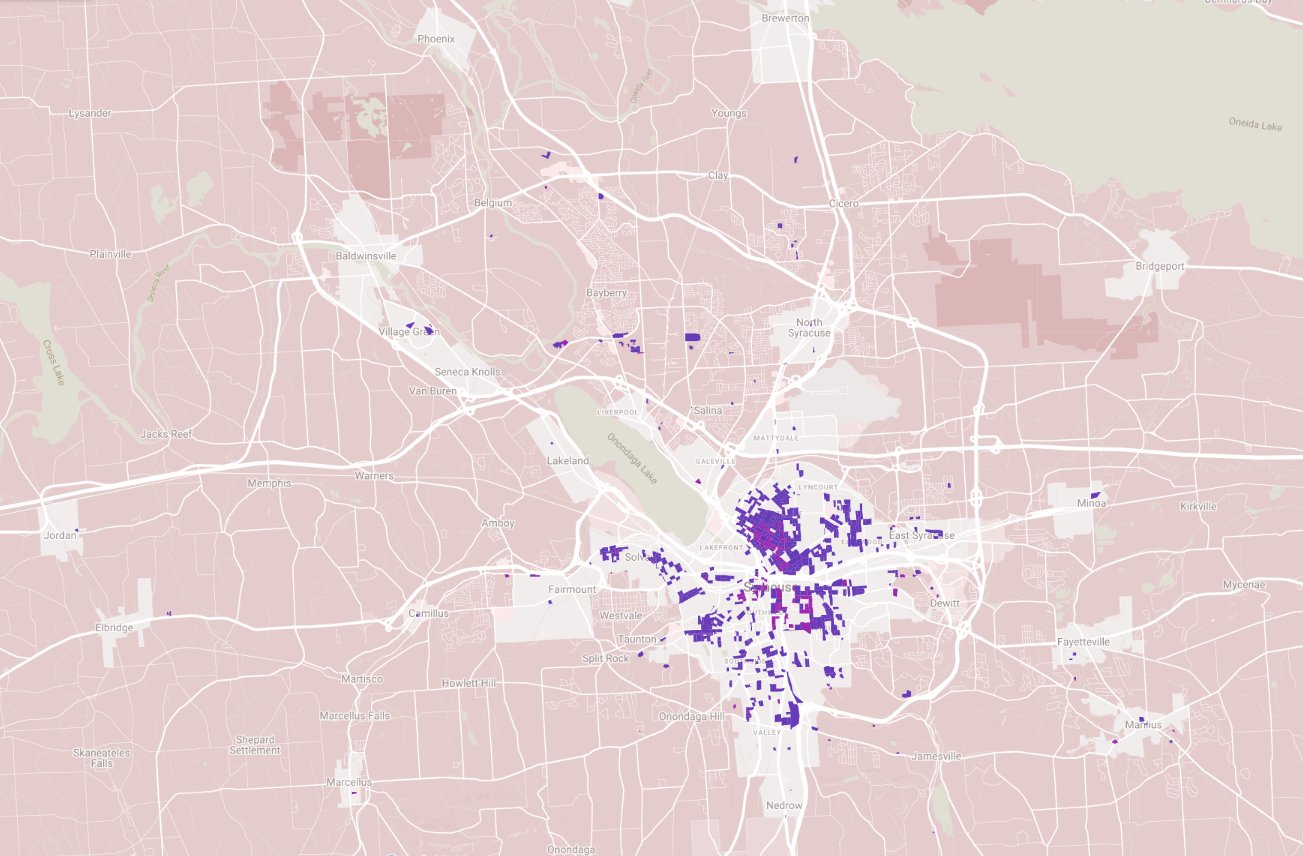

Centro just released the first draft of its proposed network redesign—Better Bus. The transit agency is proposing its first full network redesign in decades in response to changes in regional travel patterns (fewer riders need traditional Downtown-centric 9-to-5 rush hour service), changes in staffing (Centro has not been able to hire a full complement of bus operators since the depths of the pandemic, and this has forced service cuts), and changes in service type (planned BRT or Bus Rapid Transit lines and on-demand service similar to Uber pool will offer fundamentally different services that affect the entire network). This is just a first draft of the network redesign and will likely change in response to public feedback, but Better Bus is on track to go into service in early 2027.

Here’s a quick breakdown of the changes they’re proposing:

Better Service Frequency

The number one thing riders and non-riders alike want from Centro is for the buses to run more often. Existing service frequencies fluctuate across the system but rarely get better than 2 buses an hour. This makes transit a poor choice for most trips and wastes the time of the people who do ride the bus.

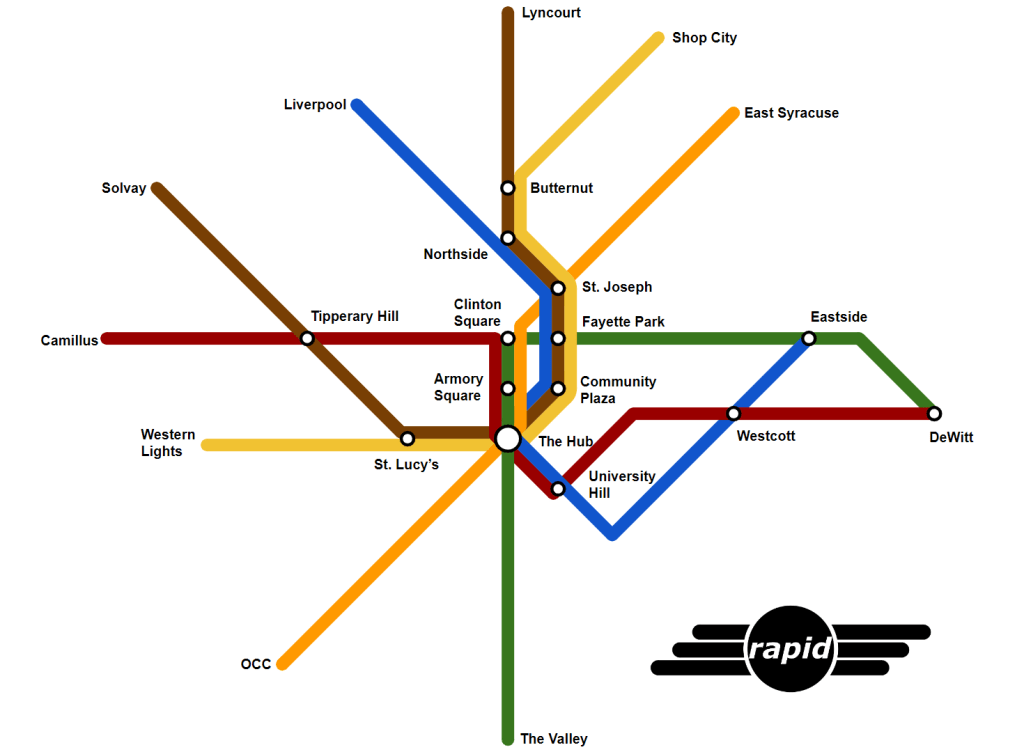

Better Bus significantly improves service frequencies along three planned BRT corridors. Lines operating along South Salina, James Street, South Ave, North Salina, and to University Hill will see buses running every 20 to 25 minutes all day every day. (These frequencies will get even better—10-15 minutes headways—once Centro implements BRT in 2028.)

Another two lines have significantly improved service frequencies that bear mention. The Grant Boulevard bus to Shop City will run much more frequently than it does now with 25 minute headways during the morning and evening rush and 40 minute headways midday and evenings. East Genesee Street will also see significantly improved service between Salt Springs Road and the Hub where two separate lines—the 76 and 62 buses—will each run every 45 minutes but be staggered so that they provide 22.5 minute headways where they overlap. These two corridors would be good candidates for future upgrades to BRT service when the resources become available.

Almost all other lines will run with headways between 30 and 60 minutes. Although this is still well below the service frequencies people need, they are a significant improvement over the status quo.

Expanded Night and Weekend Service

Right now, Centro runs buses once every 80 minutes on nights and only slightly more frequently on weekends. If you’re Downtown after 5 PM, you have the option of catching a bus home at 6:20, 7:40, 9:00, 10:20, or 11:40—if your bus even runs at all. This is a massive gap in service that makes public transit a poor option for both increasingly common non-traditional commuting and the non-work trips that make up so much of people’s social and family lives.

Better Bus would massively improve service frequencies on nights and weekends. 14 proposed lines run service at least once an hour into the evening, and 3 will provide service every 30 minutes or better. Many routes will also run later into the night. Better Bus proposes similar service improvements on Saturdays and Sundays for most routes.

Multiple Transfer Points

Currently, all connections between different bus lines occur at Centro’s Downtown Hub. The entire network is designed around bringing multiple buses to that single point at the same time to facilitate transfers, and there is no other spot in Onondaga County where route designs and timetables line up such that it would make sense to try and change buses. That allows Centro to provide seamless transfers between low-frequency routes, but it also reduces service frequency and requires many riders to ride all the way Downtown even when it’s well out of their way.

Better Bus proposes several changes to this system. The first and most obvious is that there will be several bus lines that do not run through the Hub. These include the crosstown 64 bus which will run through Downtown without stopping at the Hub, the 10 and 40 buses which act like extensions of Downtown-bound buses, and the 26 and City Loop buses which run circumferential routes connecting points outside of Downtown.

Beyond those route design changes, Centro is also amending its timetables to get away from the lineup. Proposed headways suggest that redesigned routes will take different amounts of time to complete, so it won’t be possible for all the buses to depart from and then return to the Hub at the same time. Instead of a series of lineups throughout the day, the Hub will see single buses running different routes arriving and departing almost constantly.

MOVE On-Demand Service

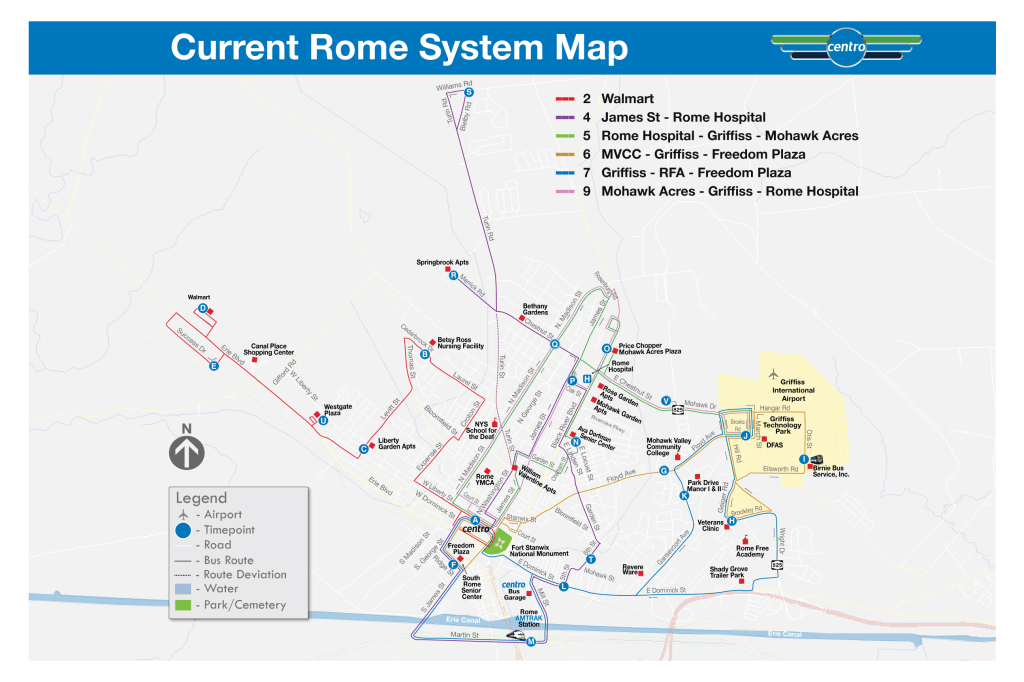

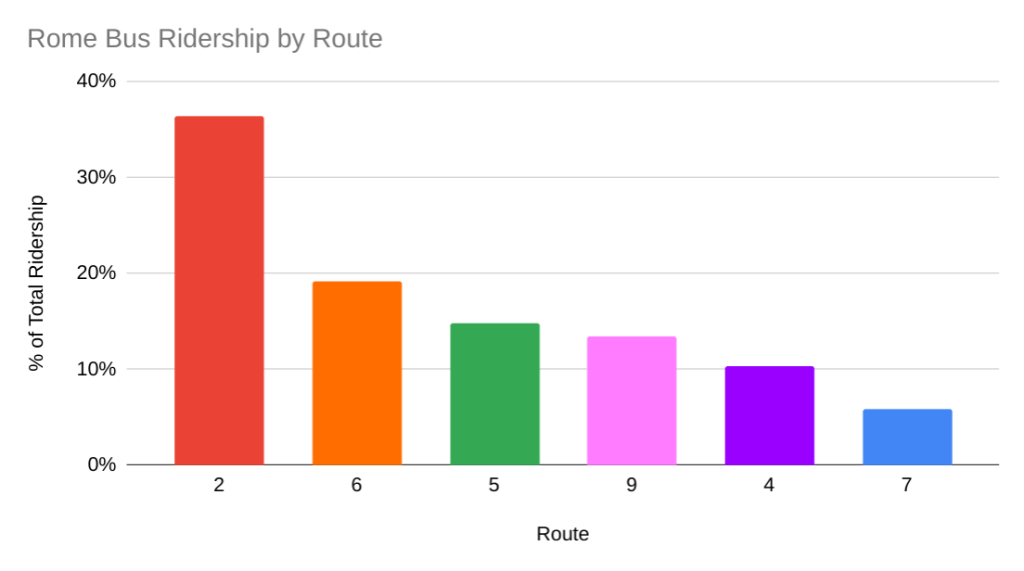

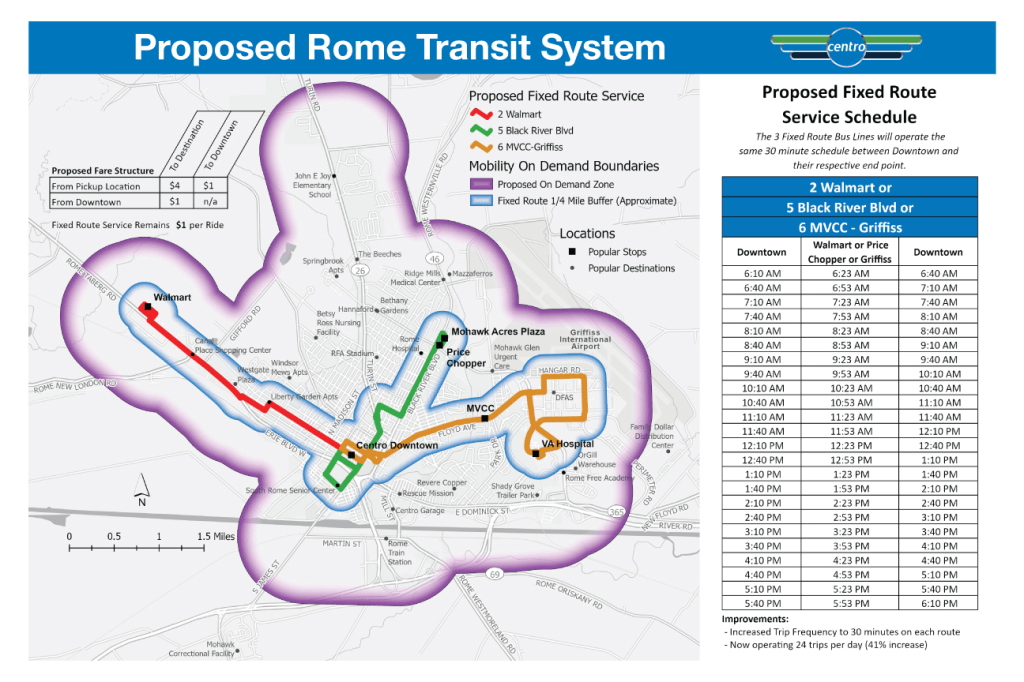

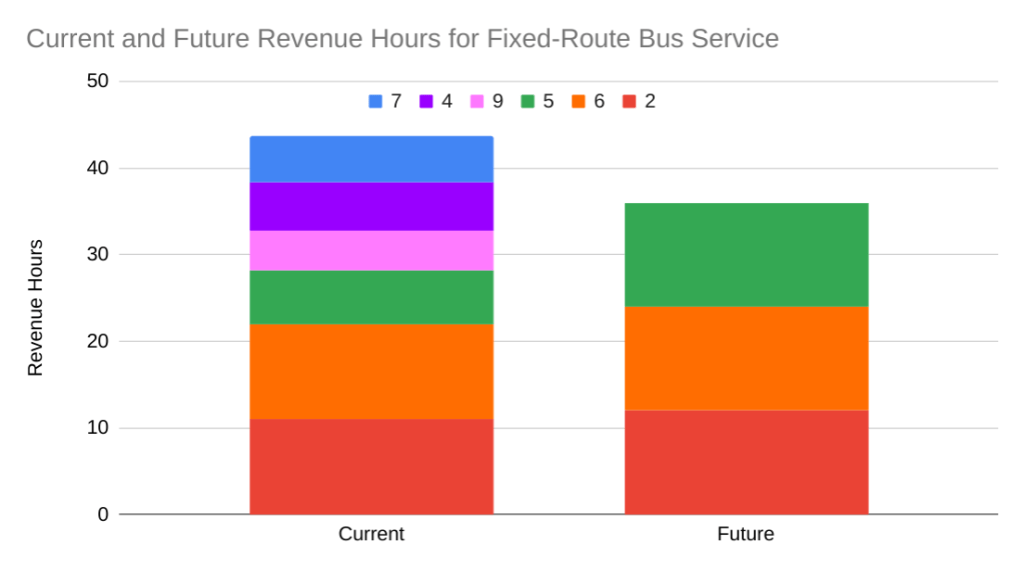

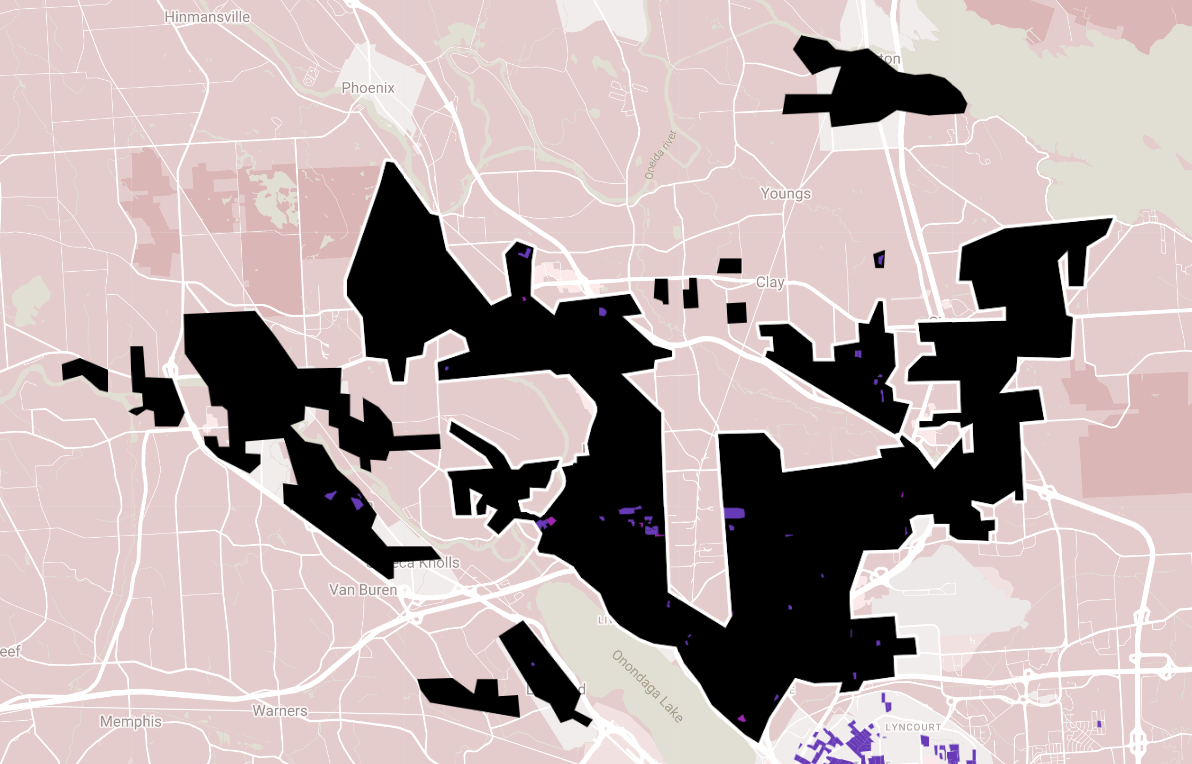

Centro hopes to find the operating resources for all of these service improvements by saving money on low-ridership corridors. In particular, it is replacing fixed-route service in three zones—Fayetteville/Manlius, Malloy Road/Carrier Circle, and Liverpool/Henry Clay Boulevard—with MOVE, a new-to-Syracuse on-demand transit service. MOVE will work like Uber Pool and dispatch small ADA accessible transit vans in response to real-time requests from riders. Centro has already launched this type of service in Rome where it has freed up resources to provide better frequency on remaining fixed-line service and led to substantial ridership gains across the system.

Service Cuts

Centro is also eliminating service in areas not covered by MOVE. In some cases, that means removing route deviations. Deviations on the current 64 bus to Western Lights, for instance, essentially mean that it is actually four different routes. All of those deviations add complexity and reduce frequency, and Better Bus proposes eliminating them on the 64 bus and many other routes to focus on one core line to provide better predictability and frequency.

In other cases Better Bus proposes removing routes entirely. The most notable is the 54 bus on Midland. Some portions of that route will be covered by other lines, and other portions are within walking distance of improved lines, but fewer people will be able to catch a bus on Midland if Better Bus is implemented as proposed. That’s the kind of tradeoff many current riders have expressed a willingness to make, but it is worth scrutinizing the tradeoff all the same.

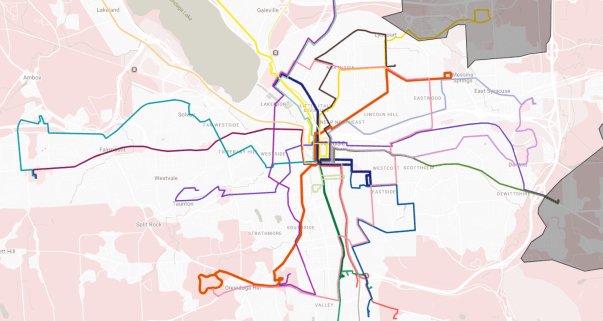

Centro released this draft proposal to get the public’s feedback, so let them know what you think! There are more tools to explore the proposed changes at the project’s website as well as an online survey that will allow you to make route-specific recommendations. You can also view the below map that shows the proposed lines in different colors. You can interact with this map and filter the system by frequency at this link.

Centro made a lot of small decisions in the process of redrawing these bus lines and reworking these timetables, and there is ample opportunity to point out places where any specific line’s zig might work better as a zag or where better midday frequency might be preferable to robust rush hour service. That’s all great feedback that should inform a second draft of the plan.

Keep in mind, though, the tradeoffs involved. Adding frequency to any line or making it longer necessarily requires reducing frequency somewhere else. Centro simply does not have enough bus operators to provide high frequency service in every neighborhood.

The good news is that Centro is moving in the right direction. The principles that lie behind Better Bus—focusing resources to improve service where it will help the most people and yield the highest ridership—are good ones. If Centro continues to follow them and if we can get them more operating resources, Syracuse will build the transit system we need and deserve.