The I-81 project can and should help build a Bus Rapid Transit system in Syracuse. BRT will make public transportation much more useful for current riders, it will attract many new riders, and it will reduce traffic congestion and improve traffic safety for everybody who uses Syracuse’s streets.

In the DEIS, NYSDOT lists “maintain[ing] access to existing local bus service and enhanc[ing] transit amenities within the project limits in and near Downtown Syracuse,” as one of the I-81 project’s five objectives. These transit amenities “could include bus stops and shelters, bus turnouts, and layover and turnaround places.”

NYSDOT elaborates:

“Apart from the Downtown transit hub, Centro has few amenities for its customers. Most stops have a sign, but no seating, lighting, or shelters. Syracuse has a temperate climate with cold winters and hot summers, and the city sees substantial snowfall each year. Lacking any amenities, customers must wait for buses outdoors without the protection of shelters. Where practical, enhanced amenities for riders could provide a better experience for transit customers and facilitate their use of existing transit services.”

This is good. It is ridiculous that the snowiest big city in the nation asks its bus riders to stand in the street to catch the bus in the winter. It is ridiculous that a town where the sun sets as early as 4:30 pm doesn’t provide adequate lighting at its bus stops.

But even though better amenities are good, what we really need is better service. Even the most comfortable bus shelter won’t do much if riders have to wait an hour for the bus to show up.

Luckily, Uplift Syracuse just released a new report—“Better Bus Service”—that shows how investing in infrastructure like better bus stops can make more frequent service more possible by speeding up buses and reducing the annual operating cost of providing improved service.

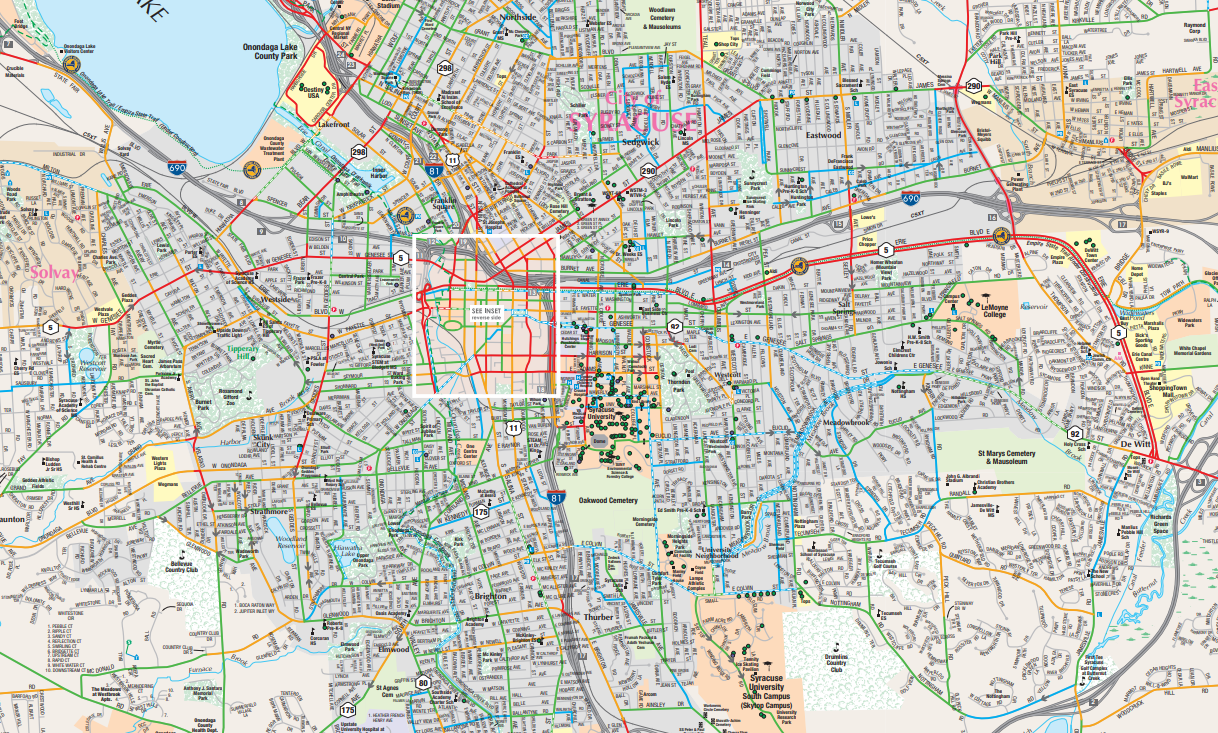

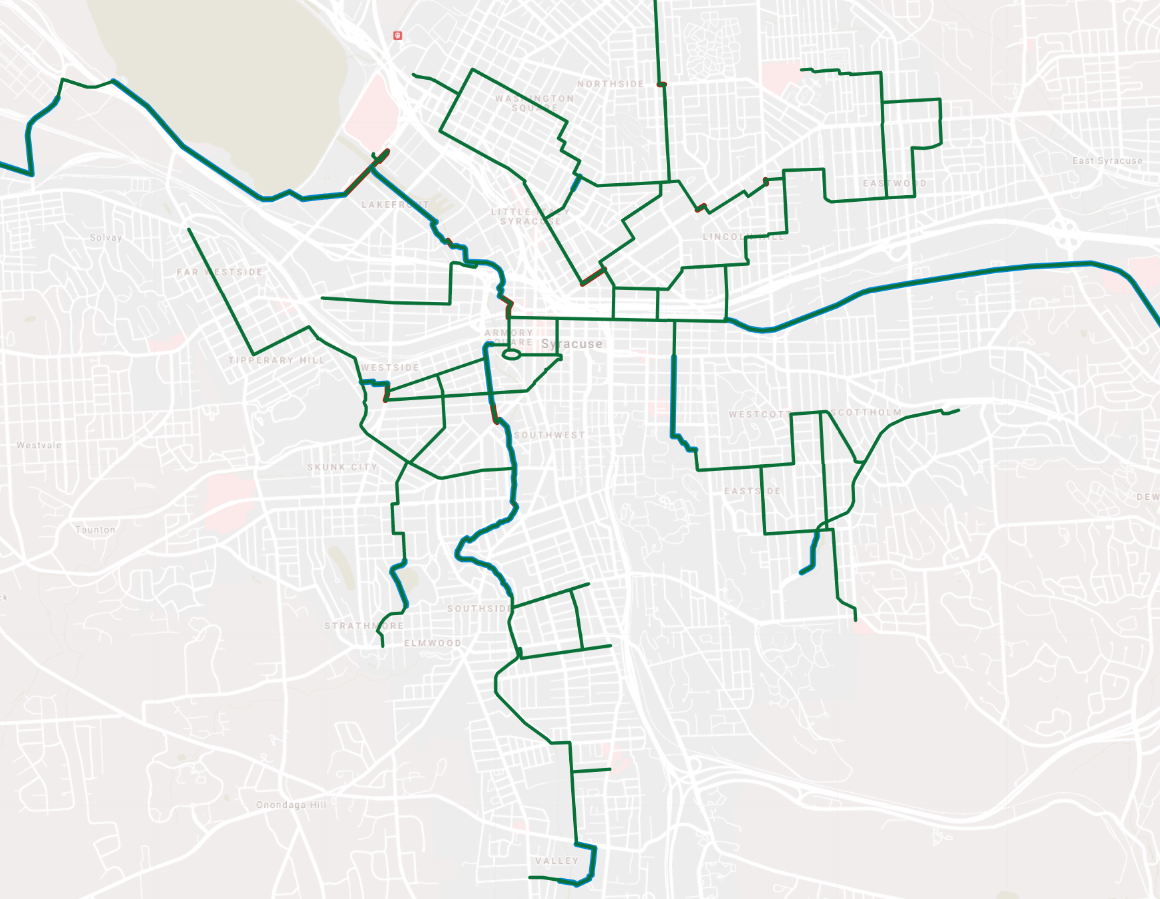

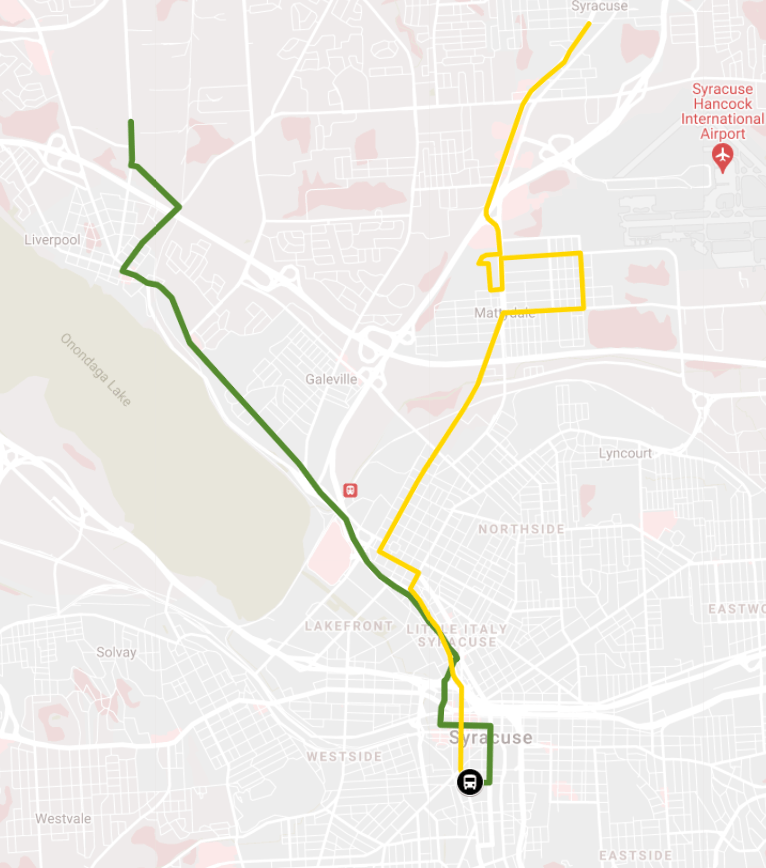

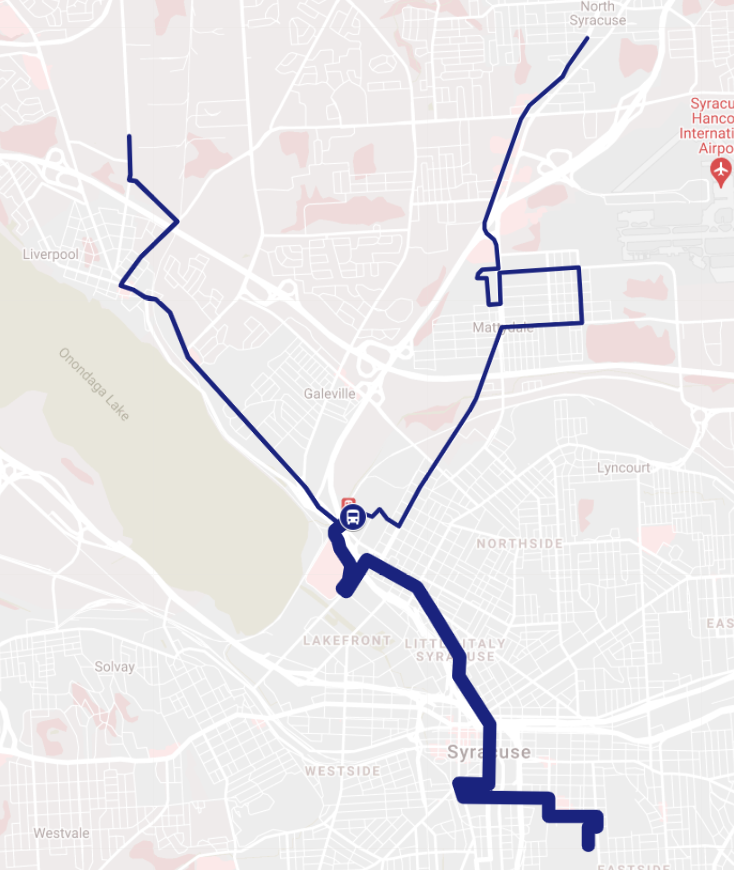

Basically, faster buses cost less to run than slower buses because they allow a single operator to complete more runs in a single shift. Uplift Syracuse estimates that if bus speeds on Centro’s best performing corridors could be increased from roughly 10 mph to 15 mph, then Syracuse could have an 8-line, 28-mile, citywide network of fast and frequent rapid transit service for roughly $8 million per year—that’s significantly cheaper than Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council’s estimate that running a network of just half this size would cost $8.3 million annually.

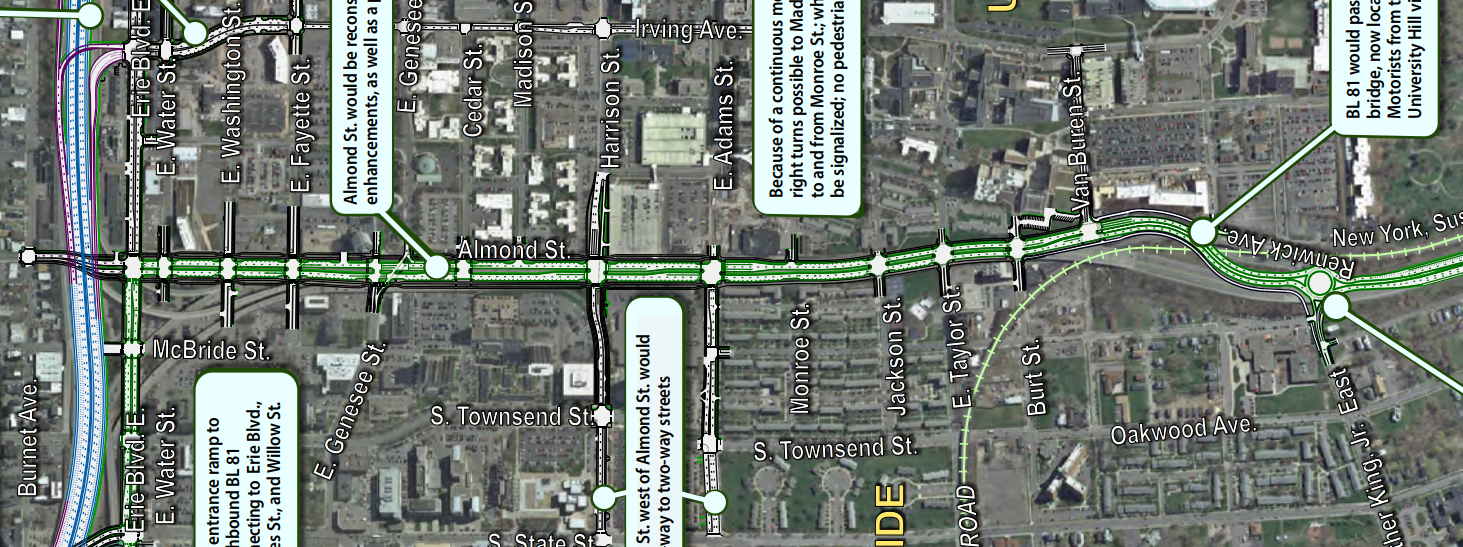

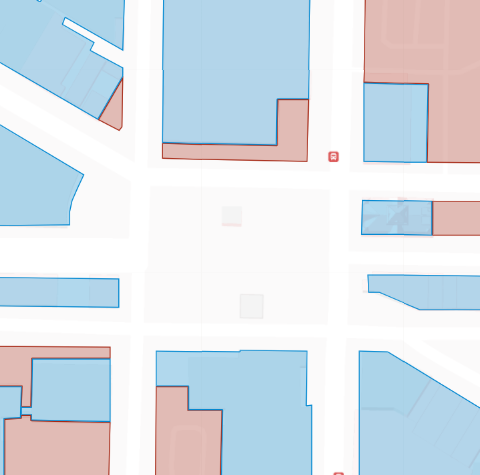

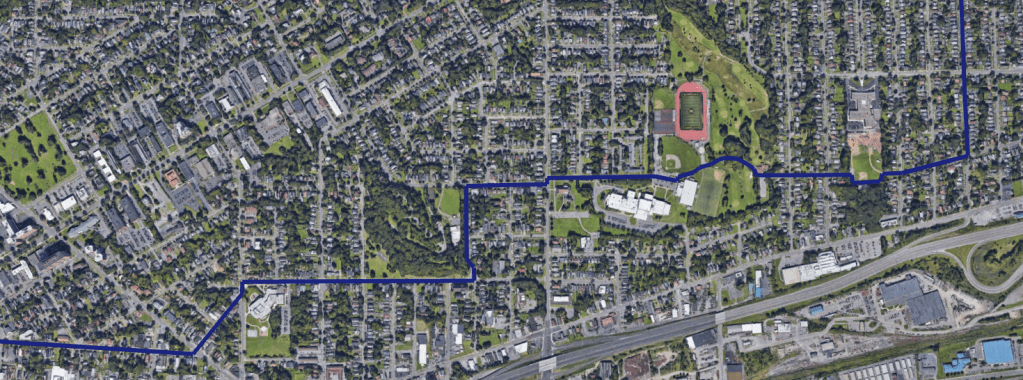

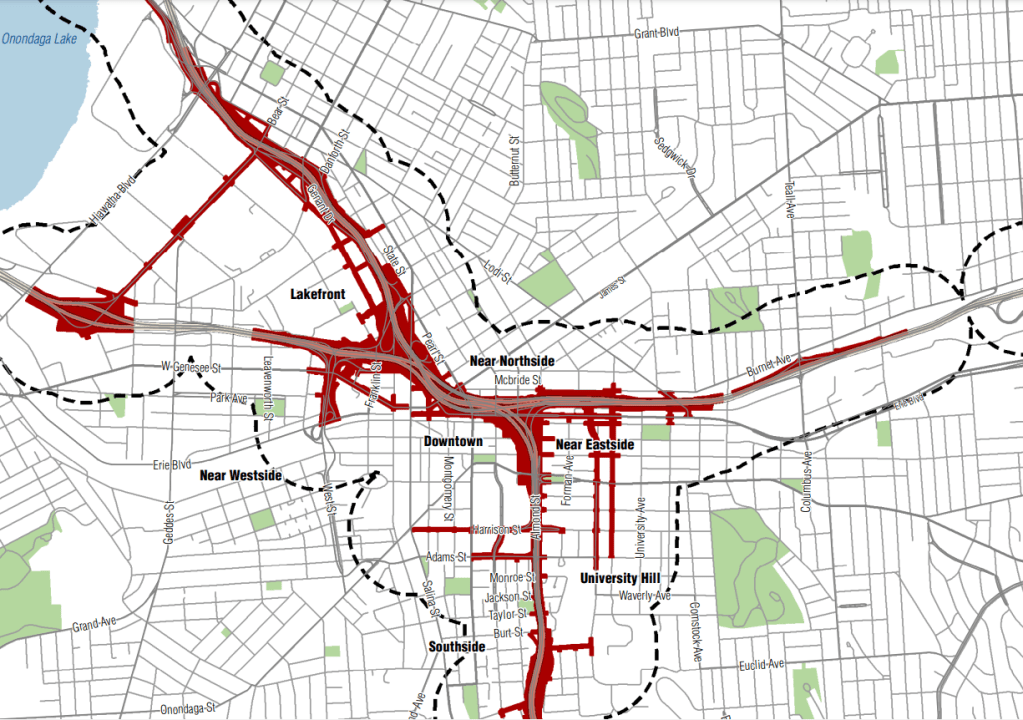

NYSDOT is willing to build new transit infrastructure anywhere in the I-81 project area shaded red on the map above. This area overlaps with much of the central portion of Uplift’s proposed BRT system. Here are the specific projects NYSDOT should build in order to advance Bus Rapid Transit in Syracuse:

New Stations

BRT stations are significantly different from the bus stops Syracuse knows now. They are more than just a place to wait—BRT stations actually increase average bus speeds by minimizing the amount of time that it takes for riders to board and alight from the bus.

BRT stations do this in two ways. First, they are raised up above the sidewalk to sit even with the bus floor. That makes it easier for everybody to get on and off the bus, and it’s especially important for people who use mobility devices. Second, they allow riders to pre-pay their fare while waiting for the bus to arrive. This makes boarding much faster because it eliminates the line at the farebox.

And BRT stations do also have the amenities that every bus station really should have: shelter from the snow, rain, and sun, a nice place to sit, lighting, and real-time information about when the next bus will arrive.

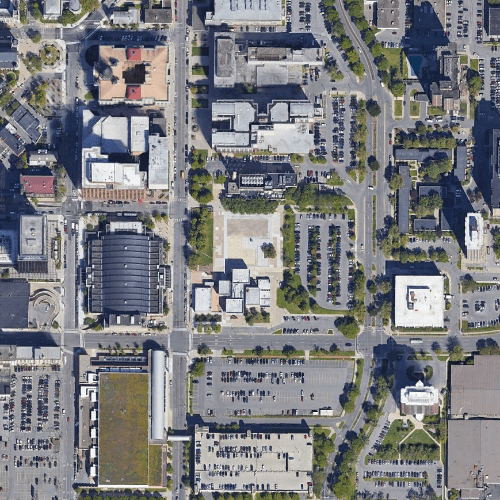

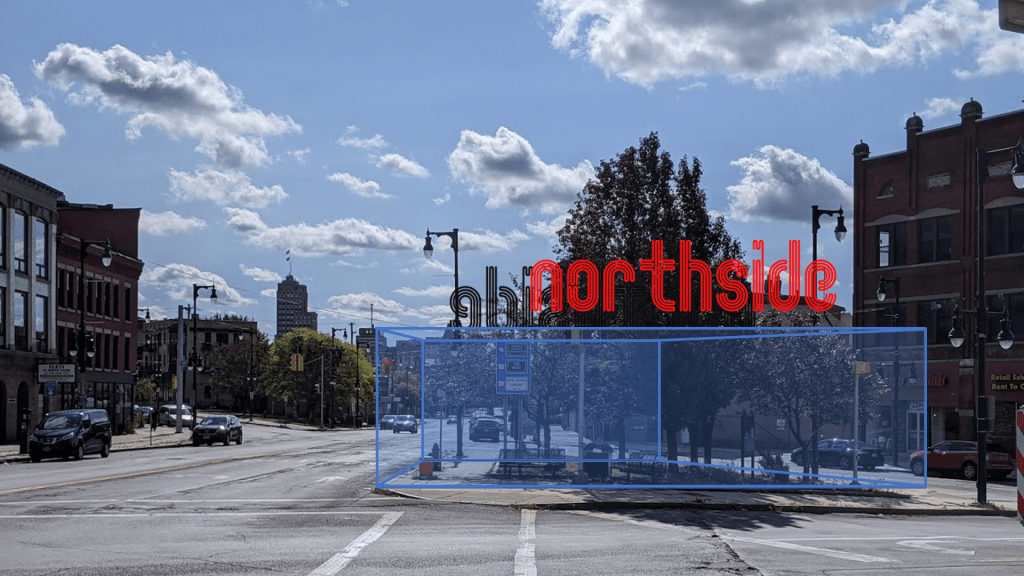

Several potential BRT stations are located within the I-81 project area. One of the most important is the small park at the intersection of Butternut, North Salina, and North State Streets. That’s where two BRT lines will converge, and a station on that park would allow riders to transfer between those lines without the need to cross the street.

Other potential BRT stations are on Fayette near Crouse and Irving, on State Street at Willow, on Adams at McBride, and at the corner of Adams and Irving. Centro needs to finalize its plans for where to locate new stations, and then NYSDOT needs to build the ones that will be in the I-81 project area.

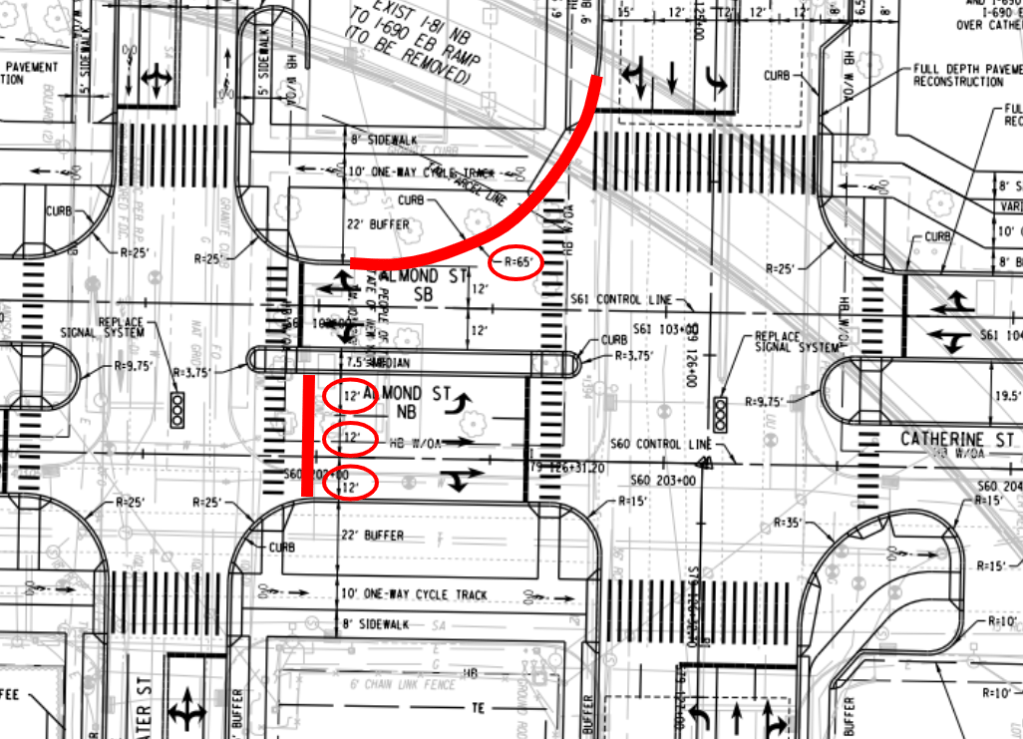

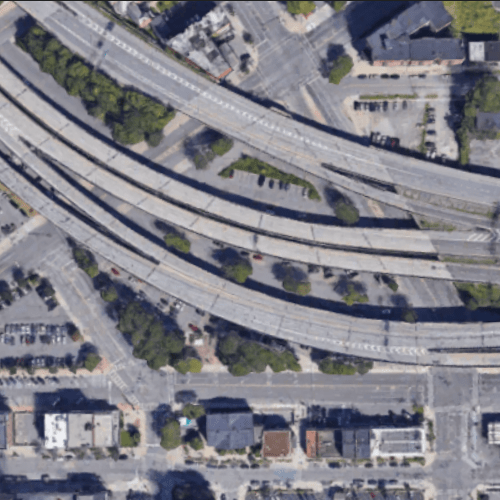

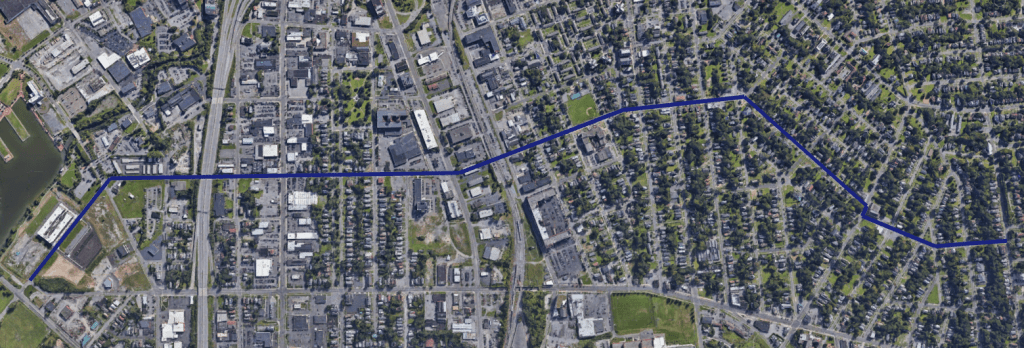

Transit Lanes

Transit Lanes speed service by letting buses bypass traffic congestion. Syracuse doesn’t have much traffic congestion so transit lanes probably won’t be necessary across most of the City, but Downtown streets do sometimes back up during rush hour. Happily, these same streets are significantly wider than they really need to be, so there’s plenty of room to give BRT buses their own space.

Major streets in the I-81 project area that might also have BRT service are Adams, State, James, Willow, and Salina. In all cases, the I-81 project area does not extend far enough to cover the entire portion of these streets that would need transit lanes, so it will be up to City Hall to complete the work of extending those lanes along State from Erie Boulevard to Harrison Street, say, or along Adams from the Hub to Irving.

These transit lanes will ensure that buses keep their schedules no matter the traffic Downtown, and that will make for faster, cheaper BRT service.

All of these minor transit infrastructure proposals are within the I-81 project area, all would meet one of the five objectives that NYSDOT has set for this project, and all would move Syracuse closer to getting the public transit system that we need and deserve. Let’s make them part of the final I-81 project.

You can let NYSDOT hear about it at this link: I-81 comment form