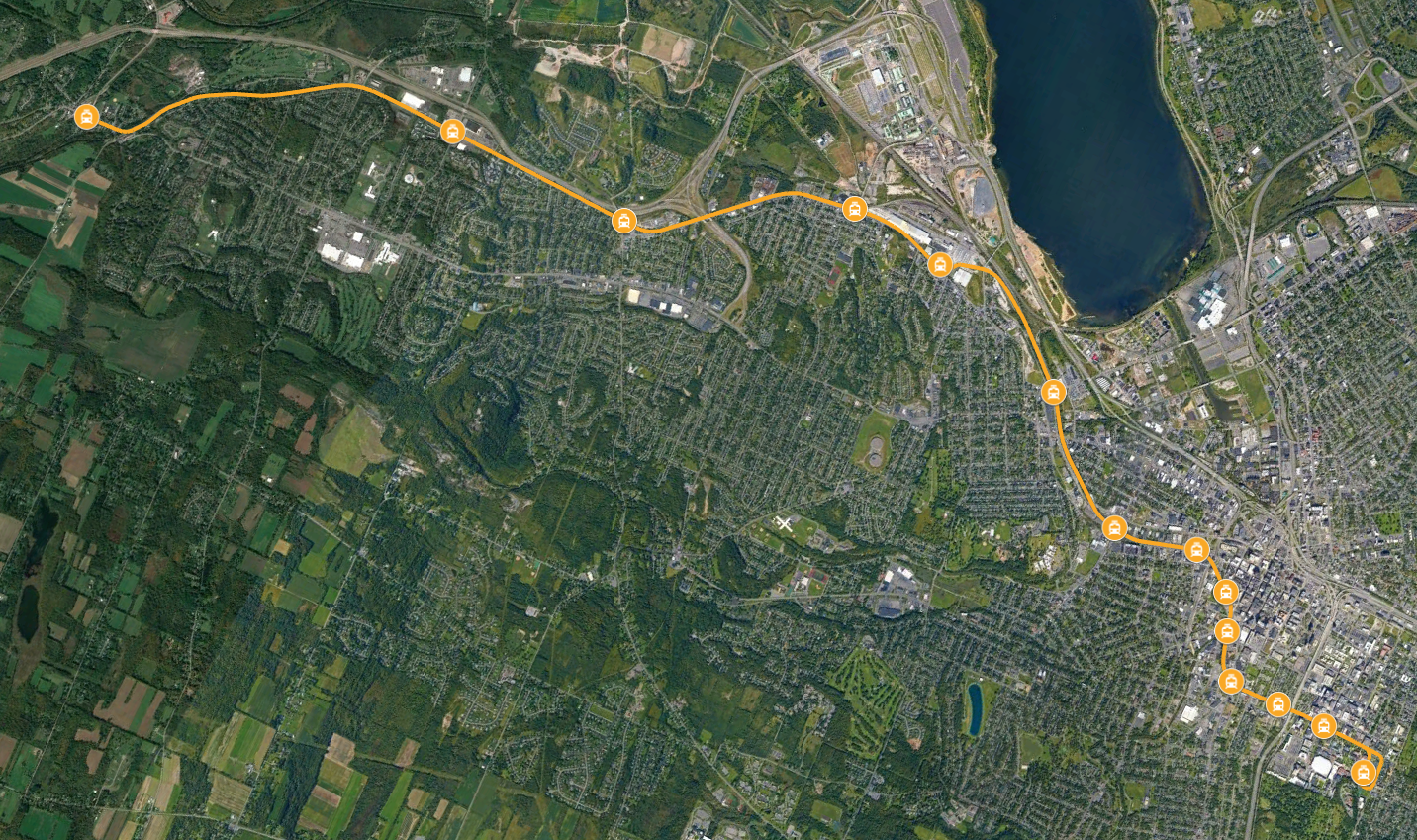

There’s not much doubt that Centro will run a bus line to the new computer chip factory on Route 31 when it opens. What’s not so clear is how good the service will be, or if it will meaningfully improve anybody’s life.

Centro designs its service—particularly suburban service—as a kind of social safety net. It’s designed for people to have to ride because they are too poor to afford a car, and because they have no other option they’ll put up with the bare minimum of service—a handful of buses a day in each direction.

This model is fatally flawed. Nobody has to ride the bus. Everybody—even people who don’t own cars—has other mobility options like catching a ride with a friend or family member, taxi services like Blue Star or Uber, and ad hoc jitney services. Centro can’t rely on ridership from everybody who can’t afford a car, because there are many other low-cost options for getting around. It has to outcompete all of them too.

And bare-bones, safety-net service simply can’t outcompete a taxi or a jitney or a ride from a friend when it comes to commuting. This kind of service offers riders one bus—one single chance—to get to work on time. If you miss it because your kid needs extra help one morning, because the bus never came, or because sometimes everybody just runs a few minutes late, you’re at least out of a day’s pay and at most out of a job. That’s simply too big a risk for anybody to take every single day, and so even people who can’t afford a car will spend a lot of money on cab fare to avoid it. The stakes are just too high.

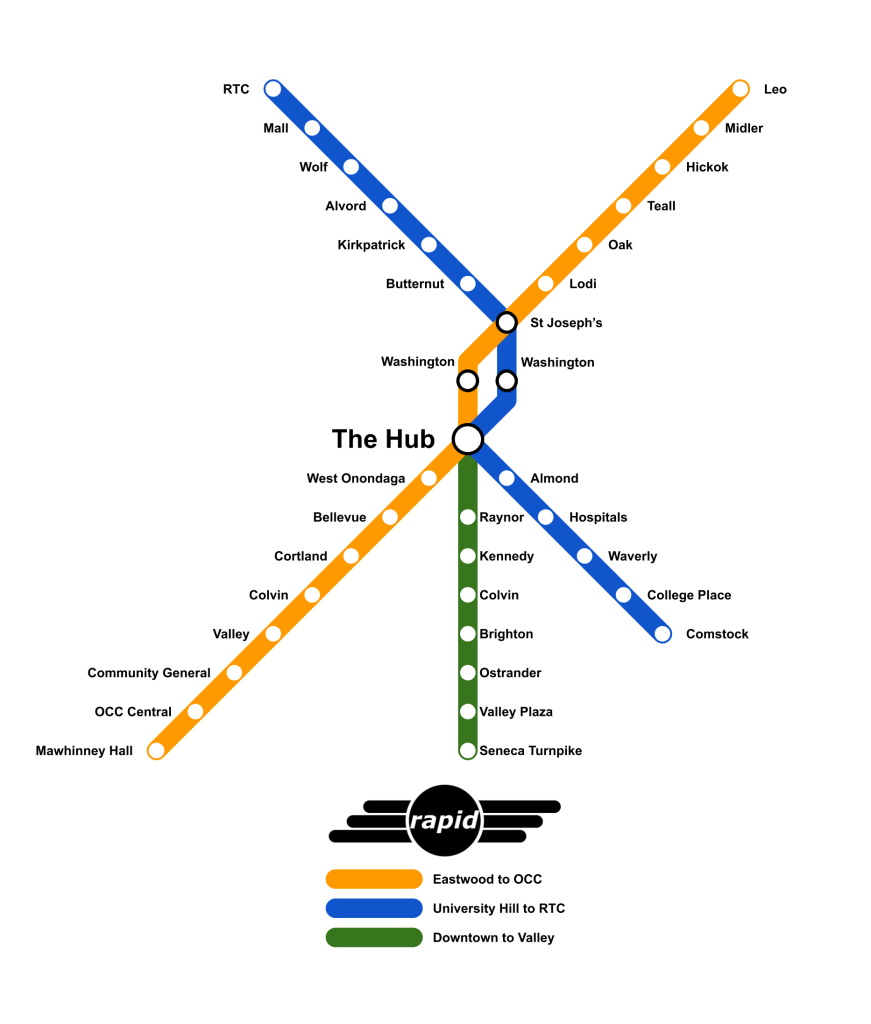

For Centro to run a successful service that people will actually use, they have to eliminate, or at least mitigate, that risk by running more buses. Frequent service—a bus every 10 to 15 minutes—gives people multiple options to make it to work so every single morning isn’t weighed down by the possibility of economic ruin. You try to catch the bus that gets you to the job with 15 minutes to spare, but if you miss that one then the next bus still gets you to work 5 minutes before you clock in. You can keep your job even if your morning doesn’t go exactly to plan.

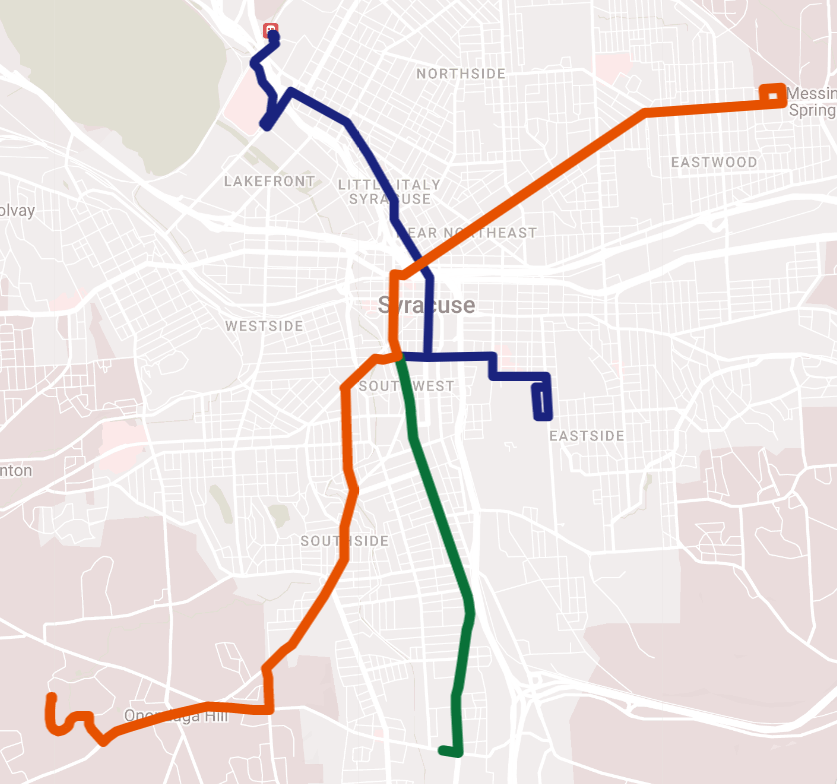

Frequent, practical, competitive transit service costs money. Centro has to pay their operators, they have to pay for gas, they have to maintain a bigger fleet of buses. Uplift Syracuse estimated that upgrading Centro’s 8 best-performing lines to truly frequent service would cost about $8 million per year, and that was before Covid made it so much harder to hire new bus operators.

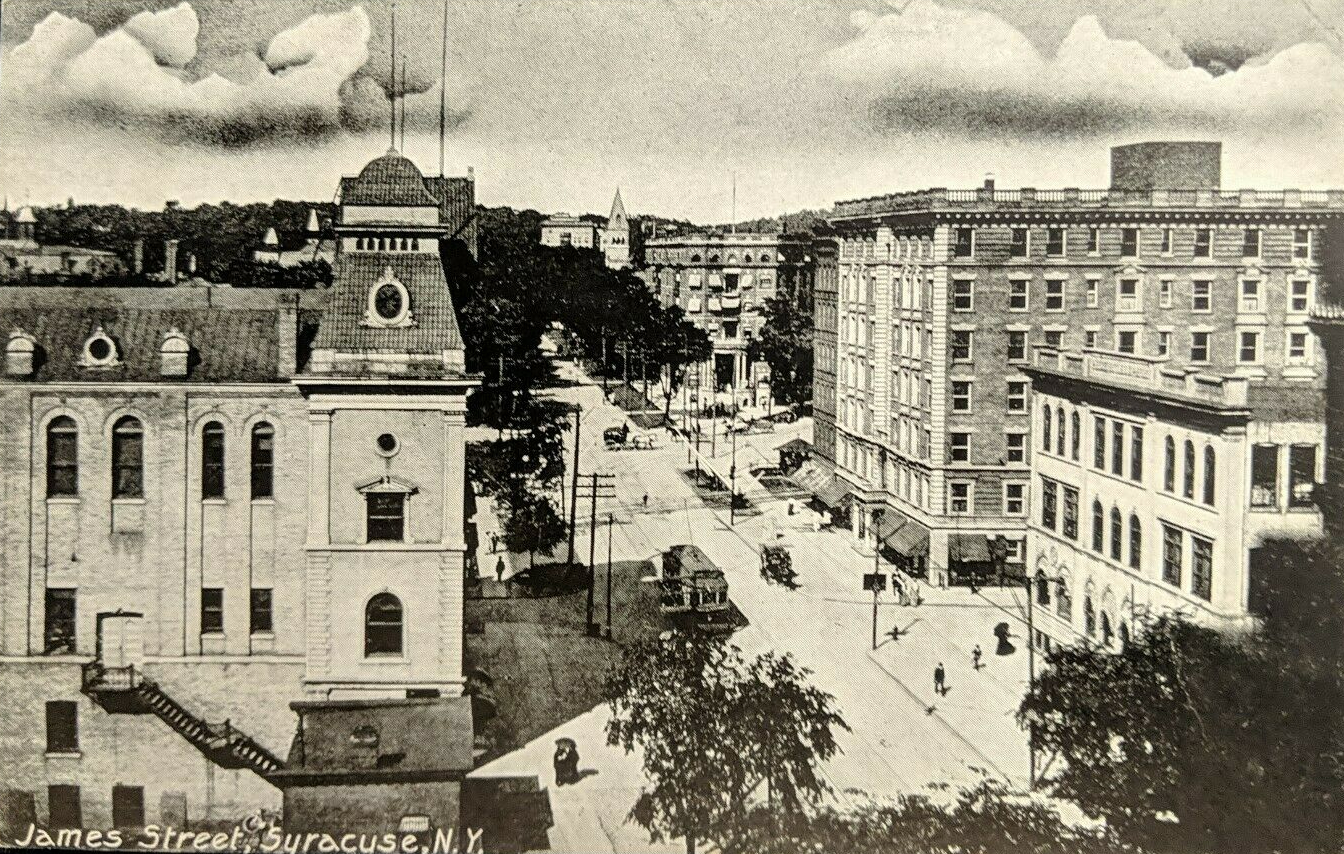

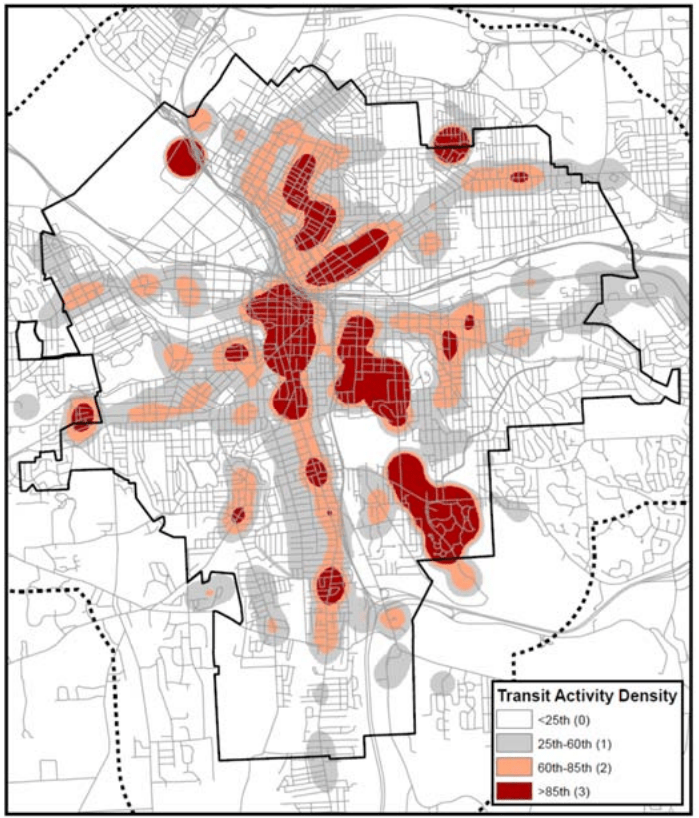

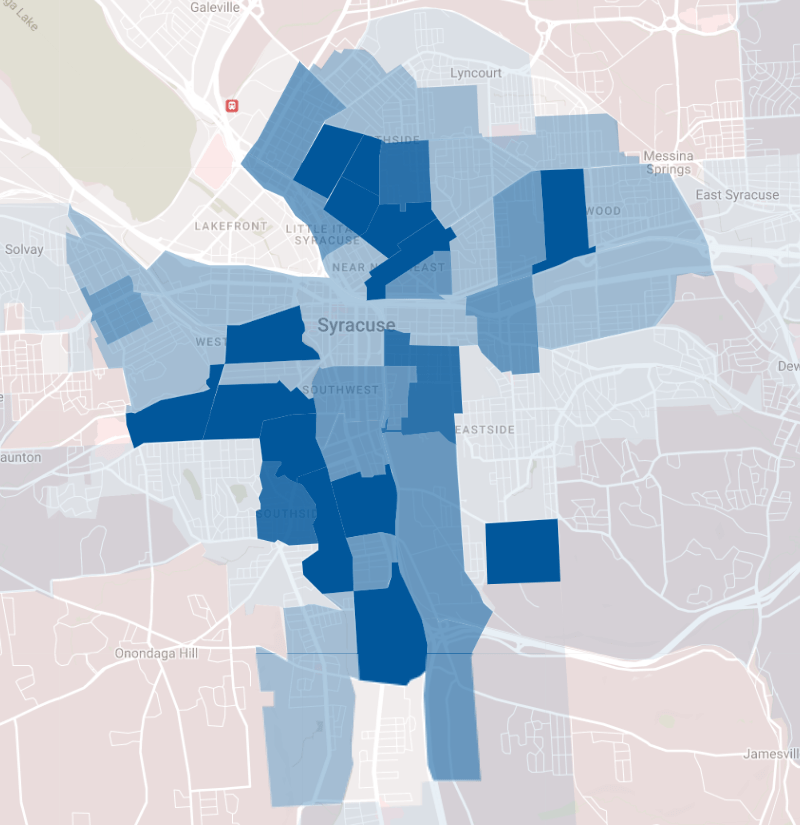

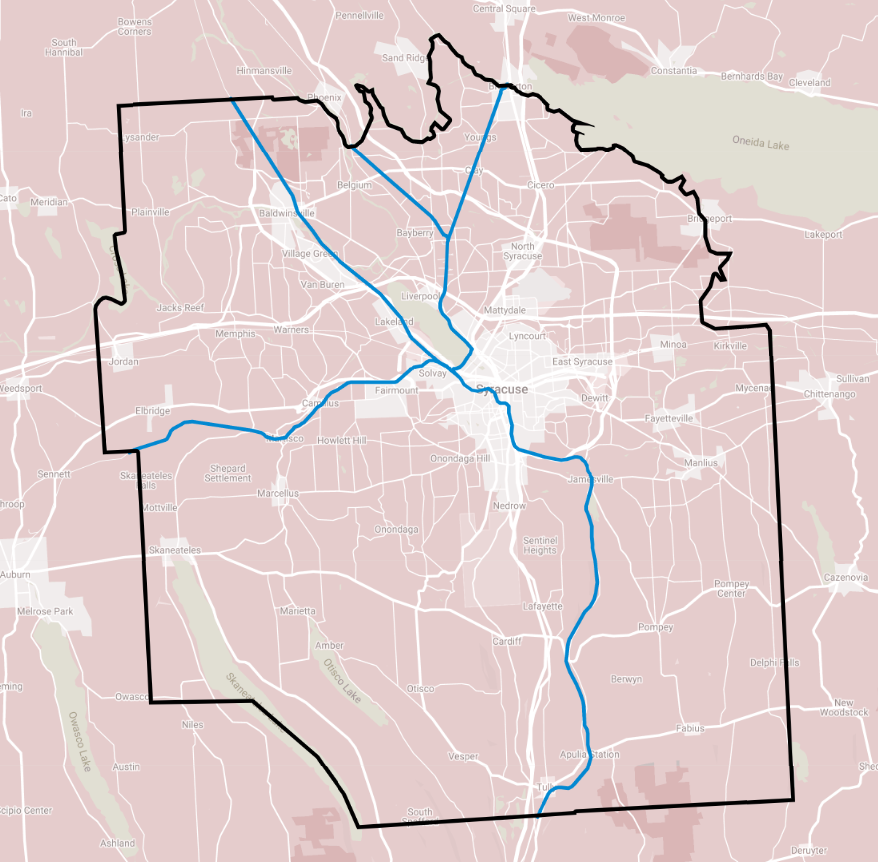

And since Centro doesn’t have nearly enough money, they rightly direct their funding to frequent service where it will do the most good: corridors where lots of people live, work, shop, worship, etc. That means James Street, Salina Street, Genesee Street, Butternut Street, Erie Boulevard, South Avenue. Centro’s best-performing lines are in the City where traditional development patterns are well suited to frequent transit service. There are currently no corridors outside the City that come anywhere near Syracuse’s levels of population and job density, and that’s why there is no decent bus service to the suburbs that anybody can rely on to get to work.

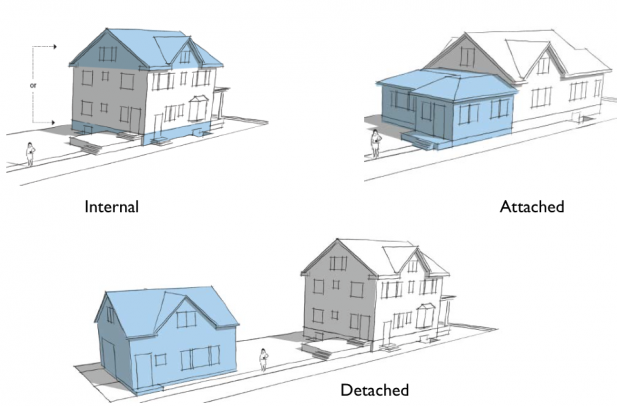

It might be possible to change that. Onondaga County just posted its first decade of meaningful population growth since 1970, and all indications are that our community will continue to grow. Those new people need somewhere to live, and there’s plenty of room for them in the urbanized area at the center of the County. More housing and mixed-use development along major suburban corridors like Old Liverpool Road, Milton Avenue, and Route 5 would create the conditions to necessary to support frequent transit service—lots of people and lots of places for them to go—and that same frequent transit service could be a reliable option for people trying to get to suburban jobs.

So here’s what it will take for Centro to run truly useful transit service to suburban employers like Amazon or Micron: lots more money, lots more housing, and much better planning. The entire County needs better bus service. Everybody needs access to all of the opportunities in this community, and this is how we can make it happen.